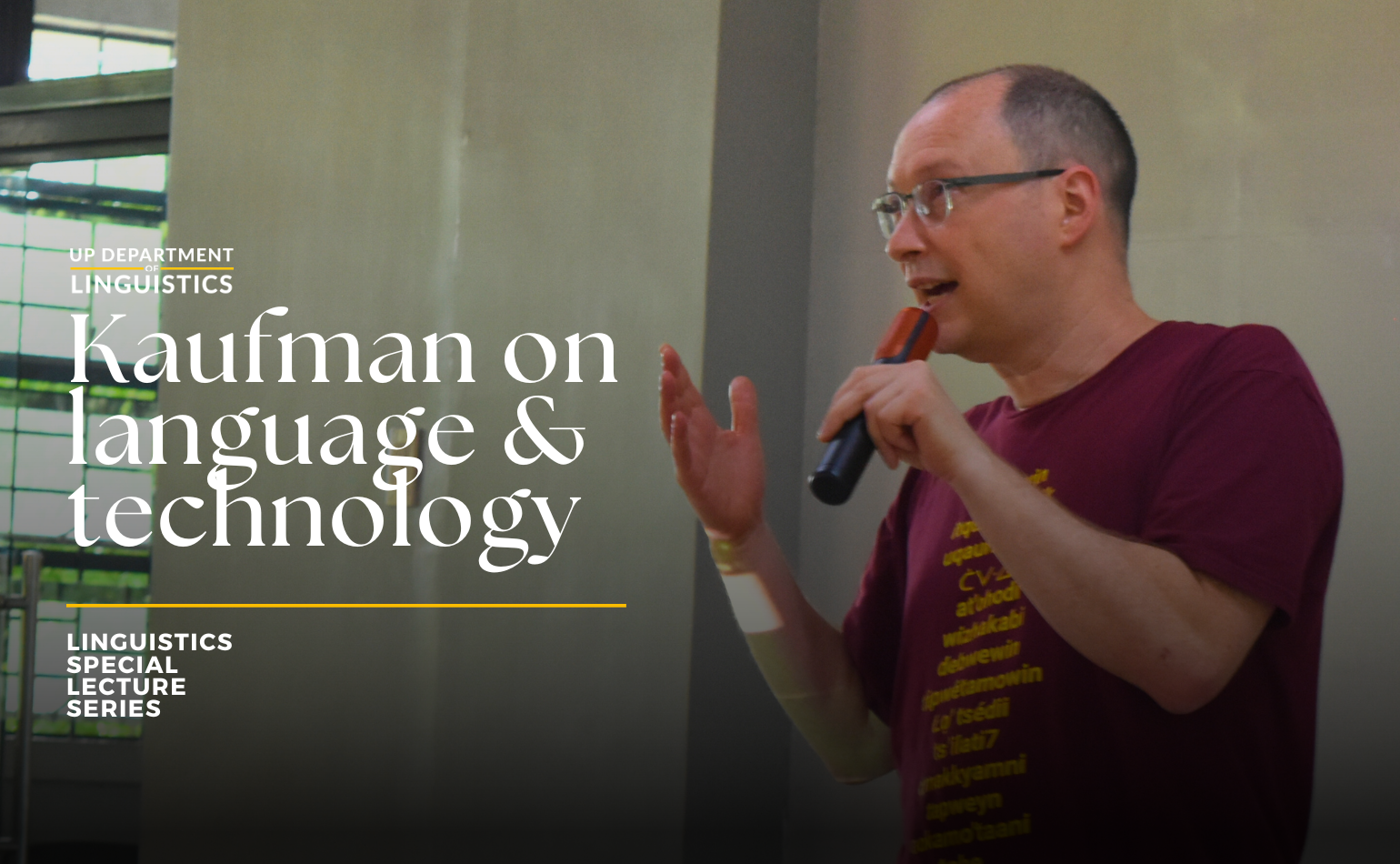

Weaving together stories about an advocacy, a fieldwork, and some technology to ponder, Dr. Daniel Kaufman (Queens College of the City University of New York) delivered the lecture “Linggwistiks sa pagitan ng kultura at komputasyon” last May 28 as part of this academic year’s Linguistics Special Lecture Series (LSLS).

The first part of Dr. Kaufman’s lecture centered on the founding story and objectives of the Endangered Languages Alliance (ELA), a New York City-based non-profit organization he co-founded. ELA collaborates with indigenous communities in conceptualizing and realizing various language-related projects, such as advertising for endangered and excluded languages; translation of infomaterials; and creation of new social domains for interaction and conversation, apart from grassroots-oriented documentation. As an ex-situ organization, ELA works in an urban environment and recognizes the city’s involvement in the discourse of migration and the disproportional displacement of indigenous communities. Dr. Kaufman explained that its establishment was motivated by the case of Mexicans in New York City who still speak an indigenous language. Migration of this population from the south is primarily caused by droughts, land erosion, and forced eviction from their homes.

Among the significant outputs of ELA is a map of languages spoken in New York City, designed to represent smaller, minority, and indigenous languages in the area. Dr. Kaufman remarked that “the new map has opened up a lot of conversations and questions” regarding the idea of locating a language in a city, the definition of “speaker,” the prospects of representation, and the notion of a map as an advocacy tool. Additionally, Kaufman talked a bit about the language revitalization efforts for Lenape (an indigenous language of New York), Quechua (a language of the South American Andes), and Hawaiian in urban settings.

The next portion featured snippets from his recent fieldwork in Taiwan, specifically his visit to the Tsou-speaking community located in the central region of the country. Kaufman contended that the overwhelming presence of indigenous images and samples of their language around the area does not necessarily correlate with the actual maintenance of their language. Peering into what is happening inside the classrooms, for instance, reveals that Mandarin serves as the primary medium of instruction and that most teachers are Han Chinese. Ironically, the community only has one Tsou speaker as its teacher, and the students are exposed to the language for a maximum of two hours a week. Kaufman noted that the support for Tsou is mainly prompted by the government’s agenda to use the community’s indigeneity as one means to differentiate Taiwan from China.

This kind of setup, in turn, still operates in and attests to the monolingual mentality and ideology perpetuated by those in power. Kaufman thus asked: “Is the language already in a ‘post-vernacular’ stage as far as the youth are concerned?” A post-vernacular language, borrowing from Shandler (2008), is a language no longer spoken regularly but which has a thriving afterlife (i.e., used performatively, culturally, but not for everyday communication).

Another case discussed is that of the Truku Seediq based on the study of Dr. Apay Ai-yu Tang (National Dong Hwa University). Kaufman highlighted that the leading challenges to the revitalization efforts for this language include the confidence of immersion language teachers (ILT); the undiscussed role and necessity of outsiders (i.e., non-Truku collaborators); and the lack of proper program evaluation. Most concerning is the fact that students only have an instrumental motivation for learning the language: Proficiency in the indigenous language exam is a means to get admitted to college. Tang thus sees the need to “create [a] social environment that can foster integrative motivation.”

Kaufman then segued to the final part of his lecture, which interrogated the suitability of artificial intelligence (AI) in addressing the predicament related to the creation of spaces for indigenous languages. Considering scenarios where avatars of researchers speak Truku and songs in Truku are generated by AI, he explained that it is actually the computers, and not the younger community members, that learn and become proficient in the language. He also brought up other concerns, such as the exclusivity of knowing how an AI program works; the unreliability of how it replicates language; and the tendency to only have computers as language partners for children.

Despite having reservations about AI, Dr. Kaufman acknowledged that different forms of technology can offer assistance to communities when it comes to language learning and/or preservation. Linguistic calculators like Morphoton (Finkel & Kaufman, ongoing), for example, can explain how words and sentences are formed in a generative manner by means of showing ordered rules. The most apparent challenge, however, is how to make this innovation relevant and relatable not only to linguists but also, more importantly, to language learners. Dr. Kaufman ended his lecture with a reminder: “Kailangan nating harapin ang hamon ng language endangerment sa loob at sa labas ng silid-aralan, nayon at pati bansa. Kailangan nating pag-isipang mabuti [kung] ano ang wastong paggamit ng teknolohiya para sa mga layunin natin.”

Some queries raised by the audience during the open forum were about the parallelisms between the experiences of Tsou and most language communities in the Philippines; the revitalization of languages with no living fluent speakers; the ethical considerations concerning the use of AI-powered programs; and plans regarding the expansion of Morphoton’s scope.

—

Dr. Kaufman is an alumnus of the Department’s BA Linguistics program. He earned his PhD at Cornell University in 2010 with a dissertation on the morphosyntax of Tagalog clitics.

Published by Patricia Anne Asuncion