This year’s Philippine Indigenous Languages Lecture Series (PILLS) kicked off with a lecture by Inst. Brian Salvador C. Baran on the grammar of Bantayanon [bfx], a Central Bisayan language mainly spoken on Bantayan Island. Inst. Baran has previously published about discourse particles in Linawis, and also wrote a grammatical sketch for the same Bantayanon variety. This in-person event, held last 31 January at the CSSP Health & Wellness Center, can also be viewed on the Department’s YouTube channel.

Bantayan is an island located to the north of Cebu and is comprised of the municipalities of Madridejos, Bantayan, and Santa Fe. Its geographical location facilitates contact with other localities that use Cebuano [ceb], Hiligaynon [hil], Masbatenyo [msb], and Waray [war]. Thus, the idea that Bantayanon is a mixed language persists within the community, aptly described as saksak-sinagol ‘hodgepodge,’ a local term commonly referring to the act of shuffling cards.

Evidence from several aspects of its grammar, however, supports the notion that Bantayanon is indeed a language different from Cebuano and Hiligaynon. Inst. Baran argued that “what makes Bantayanon distinct is its multilingual and varied context,” and that its speakers’ repertoire of languages substantiates its liminality, its being in-between and in-transition. He contended that this liminality is embedded in the language’s phonology, morphology, and syntax.

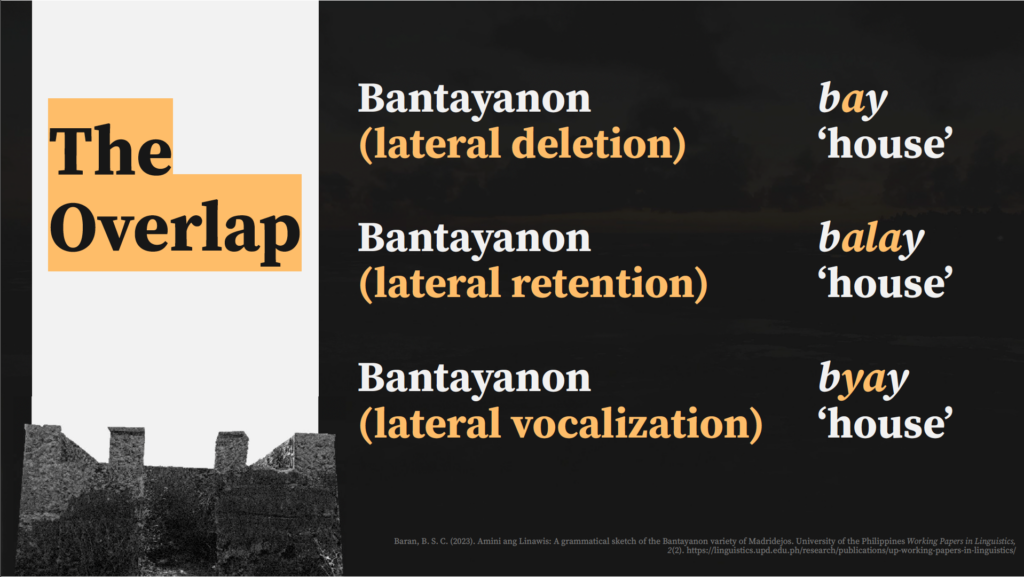

In terms of phonology, Baran noted that Bantayanon, with respect to Cebuano and Hiligaynon, exhibits a lateral-palatal [l:j] alternation (i.e., [j] is found in the environment where [l] usually occurs). While this process is also present in other Central Bisayan languages like Baybayanon [bvy], it is remarkable that Bantayanon permits overlapping or contradicting correspondences, as the following examples show.

A conversation with one language consultant further proved this point: Different forms of the term for torch—sulo, so, and syo—were used in consecutive sentences. Baran presumed that the presence of lateral deletion, retention, and vocalization in Bantayanon might be an indication of the speakers’ way of (intentionally) accommodating, for instance, those who use Northern and Standard varieties of Cebuano.

In the level of morphosyntax, liminality is illustrated in the interchangeability of the morphemes sing and =y. The enclitic =y, which marks the indefinite in the language, is also found in Cebuano, Porohanon [prh], Baybayanon, and Akeanon [akl] as a theme marker in existential, locative, and possessive constructions. Meanwhile, the markers sing and sang are used for the same function in the same context. What makes Bantayanon unique is that =y replaces sing in other clause types, which is not possible in other languages; sing, as well as sang, is not dichotomous with =y but with in in other languages. Another example of dichotomous innovation in Bantayanon is the use of both sing and og, markers that do not overlap in Cebuano and Hiligaynon.

The third example concerns particles such as the relational lat, pod, and sad ‘also, too.’ Baran recalled an informant’s anecdote regarding the usage of lat—instead of pod or sad—serving as an indicator of Bantayan origin, a shibboleth that distinguishes a Bantayanon’s speech variety from that of Cebu inhabitants. Usage of lat and its two synonyms which are of Cebuano origin are driven by a speaker’s choice based on who they are talking to. The same observation holds for Bantayanon ngay-an and Cebuano diay—the equivalents of Tagalog [tgl] ‘pala’; and Bantayanon ayhan and hili, and Cebuano kaya—the equivalents of Tagalog ‘kaya.’

Circling back to the concept of liminality, Baran highlighted that much like boundaries between barangays dictated only by administrative jurisdiction and physical markers, demarcations between languages and varieties are often not clear-cut, thus generating an awareness of a liminal status on the part of the people. Interestingly, Bantayanons navigate this through accommodation, identity-establishment, and boundary-making. Baran ended by remarking that “liminality is not particularly Bantayanon. […] [While] it’s something that distinguishes [Bantayanon] from neighboring languages…, it may also be something that we can find in the other languages of the Philippines.”

Some questions raised by the attendees during the open forum were related to the language use of speakers belonging to the younger generation; the contrast between written and spoken forms; the language’s place in the Bisayan subgrouping; and the possible variations across the three Bantayanon-speaking areas. Important works on Bantayanon mentioned by Inst. Baran include Carabio-Sexon’s (2007) lexical comparison and sociolinguistic description and Allen’s (2022) lexical and grammatical description of the language.

The first installment of PILLS 2025 was moderated by Inst. JM De Pano. Stay tuned for the Department’s upcoming events!

Published by Patricia Anne Asuncion