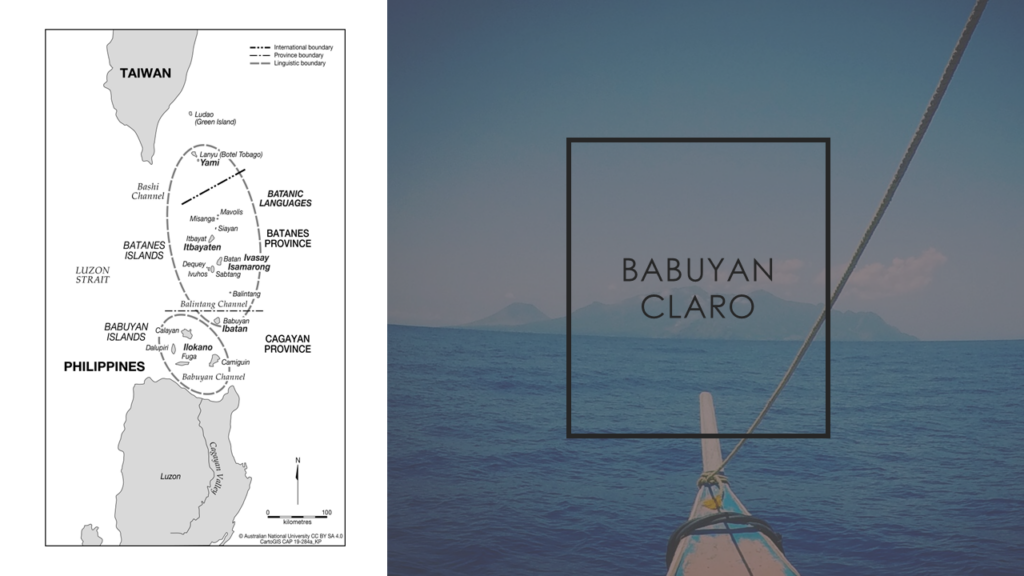

As part of the second installment of this year’s Philippine Indigenous Language Lecture Series (PILLS 2025), Department Chairperson, Assoc. Prof. Maria Kristina S. Gallego, PhD presented her professorial chair lecture on what we can learn about cognition and language processing from Ibatan (ISO 639-3 [ivb]), an endangered Batanic language spoken on the Island of Babuyan Claro in the Babuyan Group of Islands. Her lecture entitled “What can endangered language communities tell us about cognition and language processing” was first presented as a plenary talk at the 31st Meeting of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association hosted by the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has been published as the open access book chapter, The structural consequences of lexical transfer in Ibatan, published by Brill. The in-person lecture was held last 28 February 2025 at the Pilar Herrera Hall but the lecture can also be viewed online on the Department’s Youtube channel.

As part of her PhD dissertation project funded by the Endangered Languages Documentation Program, Assoc. Prof. Gallego spent months with the Ibatan community of Babuyan Claro to document their language. Although Ibatan is a Batanic language, the Island of Babuyan Claro is located within the Babuyan Group of Islands which is predominantly Ilokano [ilo] speaking making it the lingua franca of the area. Although, recent changes in the socio-political climate of the island have heightened the importance of Ibatan to the community. The island has also been historically peopled by Batanic and Ilokano communities from the early to late 1800s, some of whom were shipwrecked on the island. Being a relatively young community, the peopling of the island has been well documented in a genealogy of the Ibatan by Judith Maree published by the Summer Institute of Linguistics in 2005. Based on the socio-political landscape revealed by this genealogy, it was revealed that Ilokano has played a significant role in both the ancestral and linguistic development of the Ibatan and Gallego argues that this has resulted in a parallel verbal morphology in Ibatan and that this contact-induced linguistic feature hints at how we process languages in our brain.

The language contact situation of Babuyan Claro can be described according to different levels. Citing Pieter Muysken’s Scenarios for Language Contact, Gallego reveals that language contact can take effect first on the level of the individual resulting in Ibatan-Ilokano bilinguals but it can also affect the community level resulting in potential language changes across the community such as loanwords and loan structures. Being that many Ibatan are multilingual in Ibatan, Ilokano, and Filipino, and as Ibatan can be categorized as a higher borrower language according to Martin Haspelmath and Uri Tadmor’s criteria, the language has already experienced both individual and community level changes. The latter includes the use of either the Batanic cha- in cha-dadwa or Ilokano maika- in maika-dwa ‘second’ for forming ordinals or the competing strategies for pluralization as exemplified by the competition between Batanic maba~bakes or Ilokano bab~balasang ‘women.’ For Gallego, the most interesting effect of the language contact between Ilokano and Ibatan, however, is its resulting parallel verbal morphology.

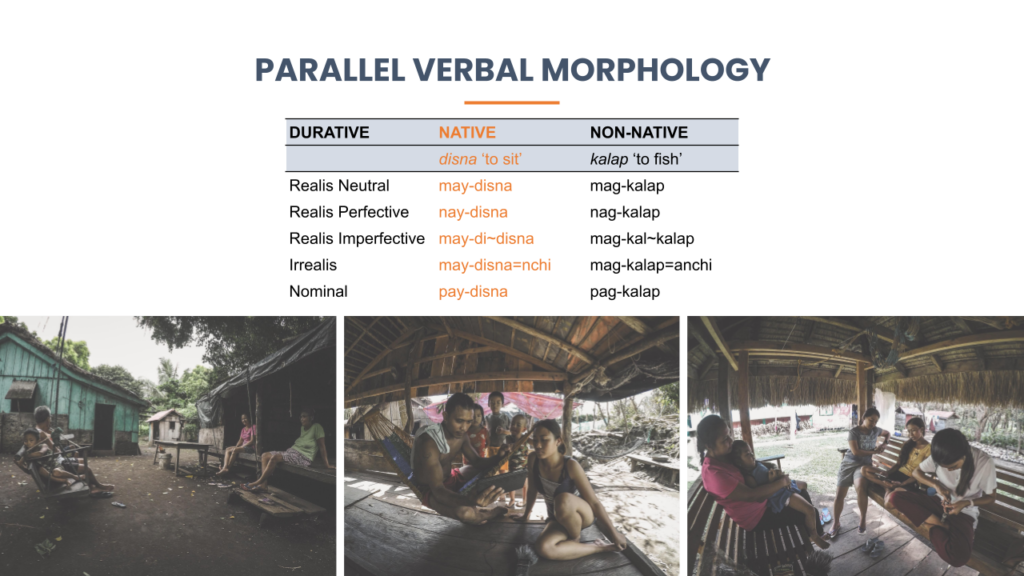

Gallego points out that the morphology of Philippine languages, which includes both Ibatan and Ilokano, is complicated since they distinguish between many grammatical categories including voice, mood, and aspect. In particular, the language contact situation of Babuyan Claro has had noticeable structural effects on the durative actor voice paradigm in Ibatan. Gallego reports that while Ibatan has a native paradigm with the pay- prefixes for native stems, e.g., Batanic disna ‘to sit’ becomes Ibatan may-disna, it also has a non-native paradigm with the Ilokano pag- prefixes for non-native stems, e.g., Ilokano kalap ‘to fish’ becomes Ibatan mag-kalap. In fact, this non-native paradigm has been regularized in Ibatan for all loanwords resulting in the Spanish loanword tiro ‘to shoot’ becoming nag-tiro but not nay-tiro. The presence of native and non-native paradigms is unique to Ibatan as it has yet to be observed in other Batanic languages. Based on a survey of Judith Maree and Orlando Tomas’ Ibatan to English Dictionary with English, Filipino, Ilokano, and Ivatan Indices published by the Summer Institute of Linguistics, Gallego found that 1436 stems can occur with the two sets of durative prefixes of which 35.72% form native stems that are used with native prefixes and 52.58% form non-native stems with non-native prefixes, totalling to 88.3% of stems showing the expected formation in the parallel verb morphology. What struck Gallego was the 11.7% presence of stems showing unexpected or hybrid formations.

Gallego categorizes the hybrid formations into type 1 formations of native stems with non-native prefixes forming 0.97% of formations and type 2 formations of non-native stems forming 4.32% of formations. The first type includes examples such as the combination of the non-native mag- and the native bwang ‘bald’, i.e., mag-bwang, and the second type is represented by the combination of the native may- and the old Ilokano stem bilag ‘to dry under the sun’, i.e., maybilag. Among these hybrid formations, Gallego also reports unexpected paradigms where non-native stems expectedly attach with non-native prefixes in simple derivations, e.g., Ilokano bosel ‘to develop buds’ becoming Ibatan mag-bosel, but unexpectedly attach with native prefixes when in combination with other prefixes, e.g., Ilokano bosel becoming Ibatan may-cha-bos~bosel ‘to develop buds together’ with the use of may- instead of mag-. She argues that these unexpected paradigms may be because meanings are encoded as combinations or chunks hence speakers result to native morphology in complex formations. This is further supported by the presence of differing meanings according to different paradigms, e.g., Spanish cuarto ‘room’ becomes the dynamic Ibatan mag-kwarto ‘make a room’ with the non-native mag- but the stative nay-kwarto ‘has a room’ with the native nay-, and the cases of free variation, e.g., Spanish apellido becomes either Ibatan mag-apelyido or may-apelyido ‘to have a surname of’ depending on speaker preference.

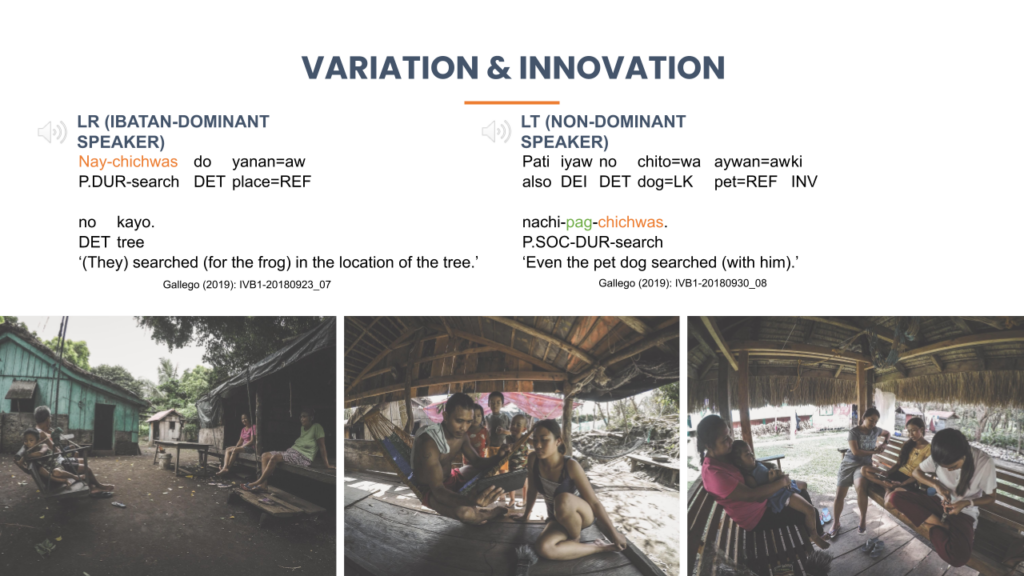

In the present-day Ibatan documented by Gallego, there were also some transient unexpected formations that many native speakers consider to be errors. These include cases of recent Ilokano-dominant imigrants who use Ibatan but with many Ilokano features such as the use of the non-native pag- in nachi-pag-chichwas ‘search’ instead of the expected Ibatan nay-chichwas ‘search’ with the native prefix nay-. Though there are only few instances of these unexpected formations, Gallego suggests that these so-called errors are evidence of imposition of Ilokano structure on Ibatan by non-dominant speakers. That said, there are also few cases of Ibatan-dominant speakers mixing forms such as the unexpected use of nag- with a native stem wakwak in nag-ka-pay-wakwak ‘dust off’ by a language consultant. Though she also points out that this particular speaker has also been away from the community for many years and is perhaps showing signs of change in their language dominance patterns. These examples show individual differences in the actuation of the paradigm that do not necessarily affect the community level of speakers.

What Gallego found interesting about the parallel verb morphology and its hybrid formations in Ibatan was the relative rarity of this type of contact-induced feature cross-linguistically. She points out that is often said that borrowing of structure, e.g., of morphology, is uncommon across the world’s languages, but as demonstrated by Ibatan, this can be overridden by other factors like typological compatibility. Being both Philippine languages with many very similar or even indistinguishable cognates and having similar complex verbal morphology, it would have not been difficult for Ibatan speakers to incorporate the loan formations from Ilokano. However, she also underscores the importance of considering non-linguistic factors the multilingualism of the people of Babuyan Claro who are already knowledgeable in both Ibatan and Ilokano and the stratigraphy of the community, i.e., the historical layers of linguistic contact and change in linguistic dominances and preferences in a community.

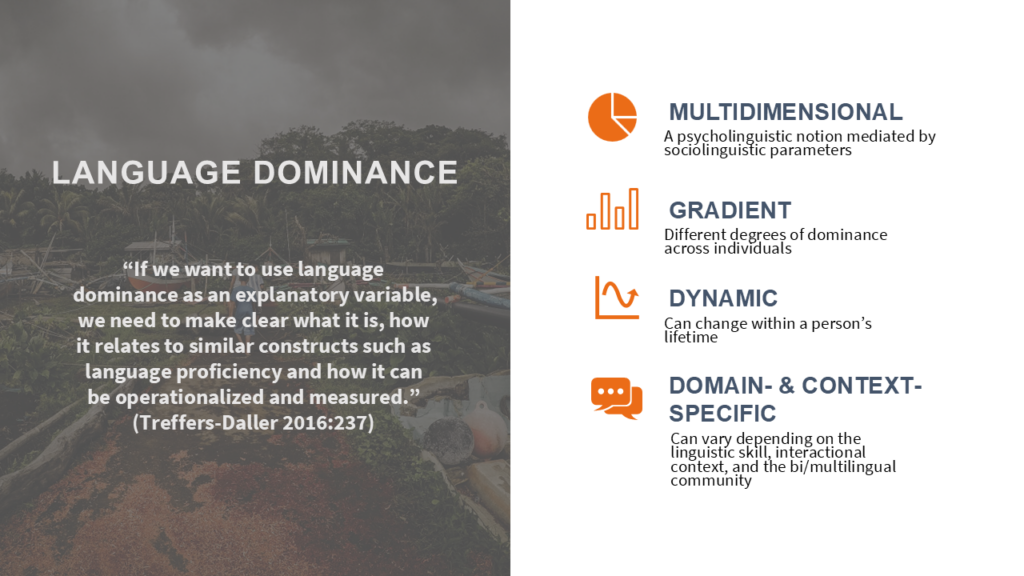

Given these different interesting examples from Ibatan of how speakers react to language contact, Gallego then asks the question, what can Ibatan teach us about language processing? Citing Frank Seifart’s Direct and Indirect Affix Borrowing, Gallego asserts that we rely on our generalizations and analyzations of patterns and simple forms and their frequencies to determine schemas of word formation. So if for example, we hear both magtiro and tiro, we can identify mag- as an affix and borrow it indirectly. Alternatively, we might also be proficient speakers of the other language and borrow mag- directly since we know how to use it. However, do we really analyze morphemes individually or do we analyze them as chunks? The Ibatan examples seems to align with our understanding of the word and paradigm approach where simple formations are analyzed as non-native + non-native chunks but the further we go away from the base, we result to native morphology with non-native stems. That said, things are also not as simple as they seem. There are also cases of different degrees of adaptation where older speakers might use the older may-tarabako ‘to work’ but younger speakers choose the newer mag-trabaho and there is also the case of language consciousness where Gallego suggest that perhaps the division between native and non-native paradigms is an unconscious effort by speakers to keep the Ibatan and Ilokano languages separate. Also, it is clear that language dominance plays a key role in the process from the actuation of an individual to the diffusion of a feature in a community. Whatever case it may be, Gallego underscores the importance of nuance or being multidimensional in our analyses and properly operationalizing our tools and terms of analysis.

As Gallego finishes her talk, it became time for the audience to ask her questions. Some of the questions asked by the attendees included the switching of affixes within the same conversation; the possibility of monolingual speakers and the period in which Ilokano is introduced to an Ibatan speaker; the formal teaching of the parallel paradigms among the Ibatan; the linguistic awareness of the difference between Ibatan and Ilokano among young Ibatan speakers; the combinatory constraints of the verbal paradigms; the phonological changes in loaned words and structures; the possibility of an Ibatan-Ilokano hybrid language; and lastly, the narrative behind the topic. For more information on the topic, a published version of Gallego’s talk, The structural consequences of lexical transfer in Ibatan, is available open-access. The talk was made possible through the professorial chair grant.

This second installment of PILLS 2025 was moderated by Inst. JM De Pano who will also be presenting the third installment of PILLS on the voice-aspect paradigm of the Bugkalot/Eg̓ongot [ilk] language on 21 March 2025 (Friday), 1:00 PM at Rm. 428 of the Palma Hall building. See you there and stay tuned for even more upcoming events from the Department!

Published by Brian Salvador Baran