Senior Lecturer Mark Rae De Chavez gave his presentation, “‘Inside You There Are Two Wolves’: Korean Grammar and Loan Paradigms,” during the first installment of the 2025 Talks on Asian Languages (TAL) last 21 February at Palma Hall 400-B.

The talk discussed the difficulty of learning the Korean language, through the different dichotomies found in the grammar, the learners, and the speakers – highlighting the need to understand both the structure and the use in order to increase proficiency: “in beginner Korean, you don’t understand what’s going on – you take it as it is. But in advanced Korean, you want to understand what is going on so that you can anticipate other words with the same process,” he remarked.

The two wolves

Addressing an audience made up of BA Linguistics majors and students who are studying Korean, De Chavez explains the different aspects that must be considered in language learning. “‘Inside you there are two wolves,’ I think, is a native American expression explaining the nature of man: you have the good, you have the bad,” he said. “So whatever part that you nurture will be the dominant part of your personality.” A similar situation may be observed in the Korean language as there is a balance between language learning for immediate use, and the linguistic analysis. Teaching for language mastery, he adds, is different from teaching the structure of the language itself.

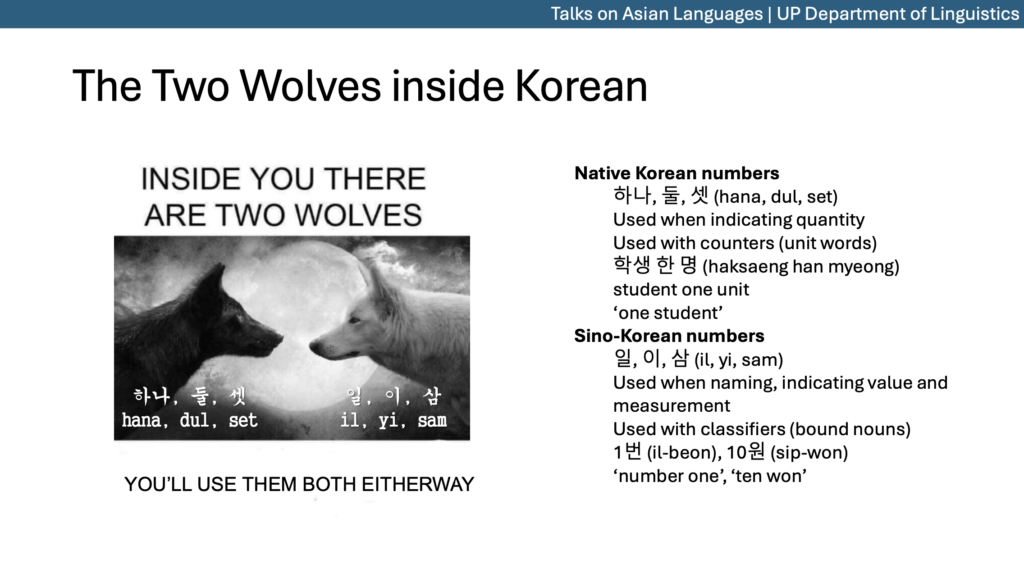

Structure, which may be analyzed through the synchronic forms of the words and sentences, is also partnered with a more historical look via etymology, and must both be looked at to understand proper word usage. The final dichotomy, meanwhile, may be seen in the existence of both native Korean and Sino-Korean words, a phenomenon that will be explained in more depth later.

Korean as a “super-hard” language

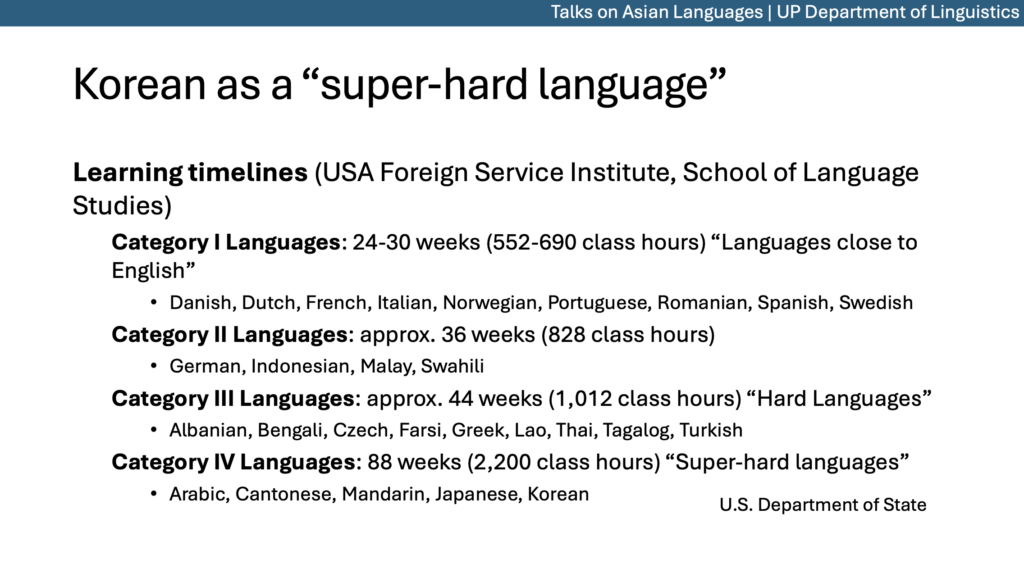

“The Korean that we teach in the classroom is often simplified to facilitate learning,” De Chavez opens the next part of his lecture. “We may base it on linguistics, but this exact description would require the students to familiarize themselves with the concepts first.” He continues by saying that Korean is considered to be a “super-hard” language for English speakers, as it requires around 90 weeks or more than 2,000 class hours before a student acquires the proficiency needed for employment.

This might be one of the reasons why looking at the recent passing rates of the Test of Proficiency in Korean (TOPIK), the beginner level has around 80 percent, while the intermediate level has around 50 to 70 percent. Other reasons for the drop could be the structure of the curriculum, the institutions offering higher-level courses, and student motivation. However, as he explains, the talk will primarily focus on the language itself, and its level of difficulty for Filipino speakers: “Korean is difficult. What is that difficulty based on?” he said.

The lexicon

The Korean vocabulary has two sets of words: Sino-Korean and native Korean. This is seen for example in count words as there are sets in both Sino-Korean and native Korean. “It is the same concept, but you have to learn it twice.” In the context of a person’s age, originally, native Korean words were used for the age, but people found it to be confusing, so the international age was preferred, and with this came the shift to the Sino-Korean terms.

Native Korean words are also considered to be basic, while Sino-Korean words are taken to be advanced. The reason for this may be language attitudes shaped by history. When Chinese was introduced to Korea, only those who were highly educated got to study the language. Because of this, the use was limited to specific domains like government functions, literature, and religion.

Out of the around one million words in the language, 35 percent are native Korean, and 60 percent are Sino-Korean (the remaining five percent are made up of loans). In order to master the language, one must indeed know both native Korean and Sino-Korean words, and to achieve proficiency for work must know around 700,000 individual words.

There are, however, interesting cases: several words that include Sino-Korean morphemes were actually coined in Korea. This means that if one translates these Korean terms to Chinese, the result would be “weird.” All of these factors above, especially when combined with each other, make the module of vocabulary a very difficult part of learning Korean.

The sounds

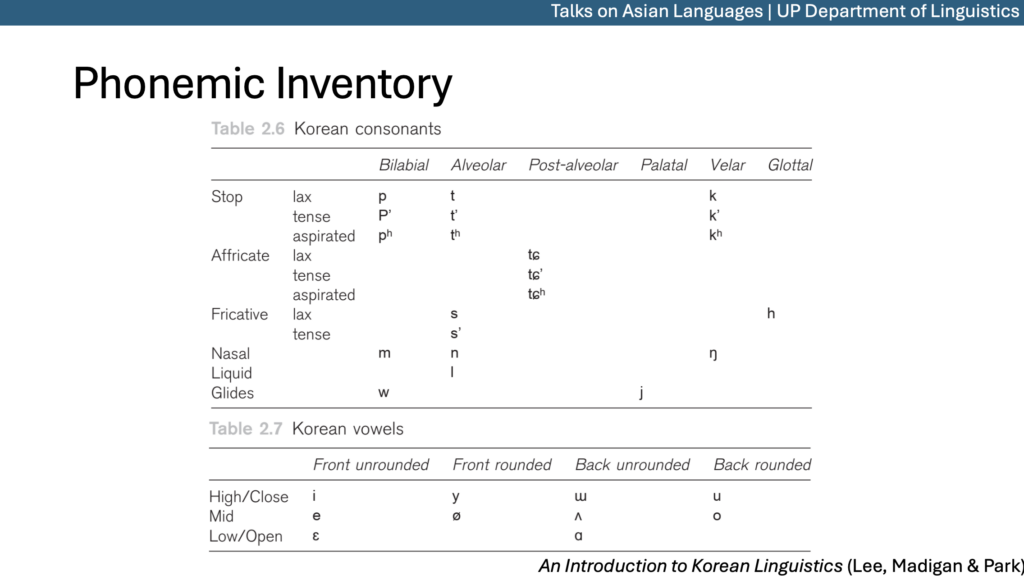

De Chavez discusses the sounds in Korean by illustrating the need for proper pronunciation–a topic usually tackled in foreign language courses: “[The proper pronunciation of words] is important for comprehension. If you don’t pronounce these words carefully, it can be confused with other words–affecting comprehension,” he explains. “Pronunciation is quite difficult. It has to be discussed every semester, even in advanced courses.”

After giving a crash course on the phonemic inventory of Korean, he then proceeds to relate the sound changes that occur in the language. While the d/r alternation and palatalization are relatively common, some unique processes found in Korean are nasalization (making sounds into /n/, /m/, /ŋ/ – the sound of ng in Tagalog), liquidization (which involves /l/ and /r/), vowel harmony (making vowels share articulatory and/or acoustic features), and epenthesis (the addition of (a) sound(s) within a word). He however says that while linguistic concepts greatly help in the studying of Korean phonology, there are instances where the cultural aspect must also be consulted: “in Korean, they have ‘light’ and ‘dark’ sounds. It would be hard to explain them from a purely structural viewpoint as these notions have been constructed culturally,” he added.

In the specific context of Filipino learners, studying the sounds in Korean is relatively easier compared to the experience of a monolingual speaker due to our multilingual situation. “Multilingual students tend to be more sensitive to sounds because of the different Philippine languages that they already speak.”

Next, writing, in contrast to the sounds, is not that difficult as the hangul system is alphabetical, i.e., one symbol represents one single sound. The only difficulty is for beginners, as the symbol itself is quite similar to one another for the untrained eye.

Going back to the “super-hard” language

For his conclusion, De Chavez circles back to the dichotomies in Korean, and explains that there are two types of instructional materials: those that are highly informative, and those that are mainly for exposure. On one hand, if a teacher only focuses on the former, the student would not be able to communicate. On the other hand, if students are only given materials that are for exposure, they would make systematic errors that could have been prevented through a discussion of the language’s structure. The balance between the dichotomies was emphasized, and De Chavez proceeds to explain the “difficulty” of Korean by looking at every module of the language that has been discussed so far: pronunciation is quite difficult, vocabulary if very difficult, grammar is mildly difficult, idiomatic expressions are very difficult, and culture is not that difficult.

He then returns to the category of Korean. While for English learners, it is a Category IV language, meaning that it is a “super-hard” language, he believes that for Filipino learners, it is a Category II language, meaning that it would take a little longer to master than Category I languages, or those that are closely related to English.

—

A recording of the talk may be viewed at our YouTube channel. Stay tuned in for the next TAL installment and other events by the Department!

Published by John Michael De Pano