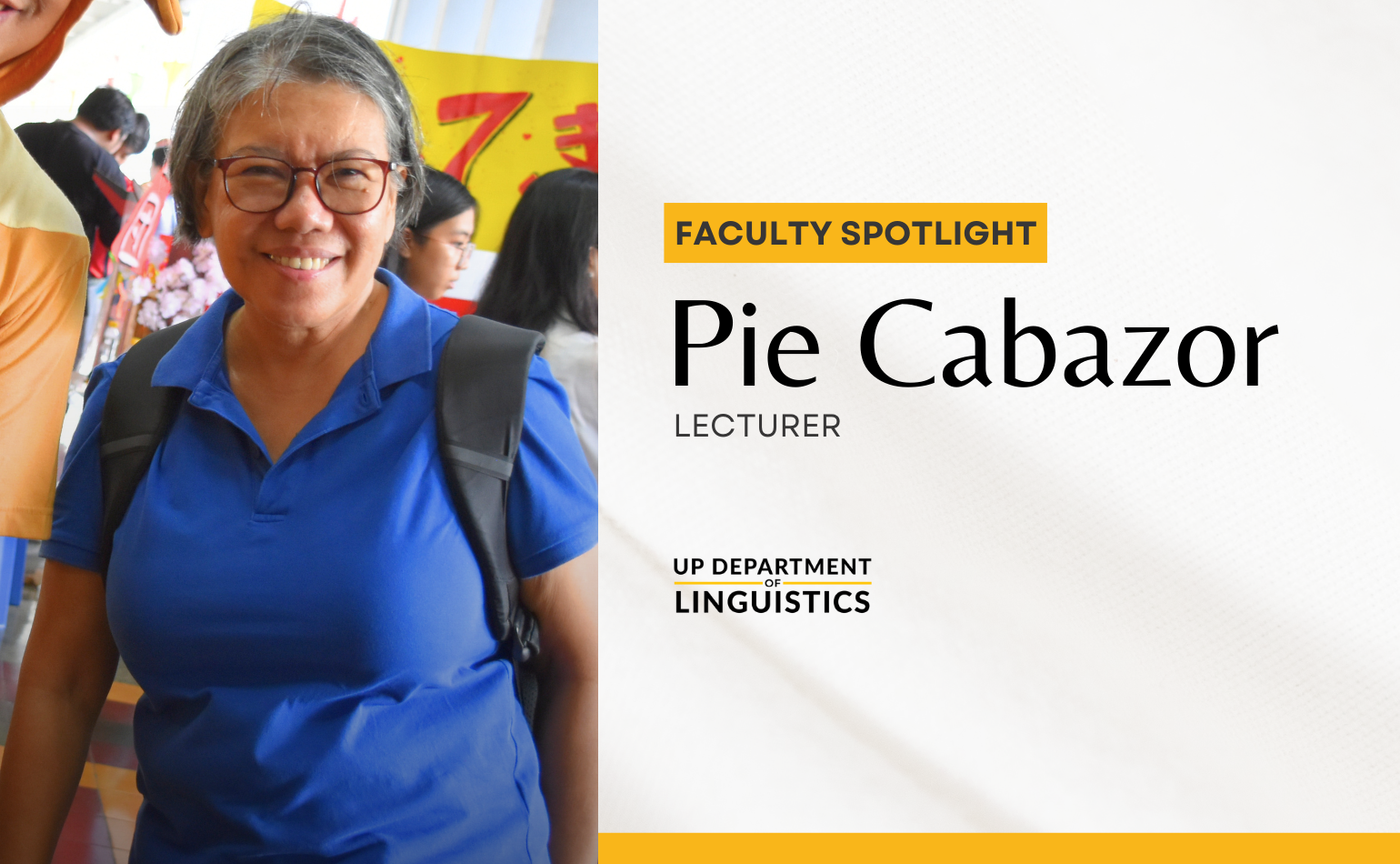

In this faculty spotlight, we feature the Japanese language cluster’s most experienced member, Lecturer Athena D. Cabazor, known to her students as Pie-sensei. She has been formally teaching nihongo for almost three decades, and has witnessed the different trends in foreign language (FL) education–from the “old-school” direct translation method, the textbook-based and gamified modules, and the performance-based requirements. Read on to know more about her origin story, insights on FL, and reflections as a teacher!

Why Japanese?

“My reason was primarily practical: I lived near the Japanese Embassy,” Pie-sensei said. “I was a Tourism major in undergrad, and we were required to learn another foreign language aside from the mandatory Spanish. Most of the students then chose German and Russian, but I preferred Japanese because of the location. I didn’t have any special interest in it at first, so pinilit ko talagang matuto.” She shares that an 80-peso cycle ran for five months (July-December and January-June), and provided free textbooks. Housewives were the usual students, who started nihongo because of their interest in its culture: “their hobbies were ikebana, teien, and Japanese cuisine,” she added.

When Pie-sensei enrolled in a cycle, the sole textbook was “How to Use Good Japanese,” a 182-paged work published by The International Students Institute of Japan in 1973. She shares that it was not that friendly for those who have no background in the language as the first lesson was differentiating the functions of the particles は (wa) and が (ga). There were no conversation partners outside of the class of 10 as well, and the large chunk of the class relied on a question-and-answer portion with the teacher to train the students in the sounds of the language. During that time, these teachers were not trained–Pie-sensei’s was a former announcer at NHK, or the Japan Broadcasting Corporation. “In the writing part of the class, we had to do a kana demonstration on the blackboard. I don’t remember learning the full hiragana and katakana charts even during the first five months of the training,” she recalls.

The origin

Before becoming a sensei, Ms. Cabazor was a travel agent “for the longest time,” aligning with her chosen degree. She had taken Education units in university, but did not take the Licensure Examination for Teachers (LET). “I entered teaching serendipitously. I was 35 then, and was asked to be a replacement when the original Japanese-language instructor became pregnant. My first contract was for 12 hours. The students were employees of the Heritage Hotel in Manila.” Back then, she observes, students learn faster, but are not adept to resources: “the teacher is everything. We tended to use information gap exercises; modules were not necessarily used as the primary material.” When asked why she agreed to the gig, Pie-sensei quickly replied, “The Skyway was under construction. I needed to kill time.”

On the different types of students

“I’ve met the best and the worst–but I connect better with students who prefer to think logically. Identifying patterns is key,” the teacher explains on the compatibility between the educator and the student. She believes that the similarity (and difference) in the teaching/learning styles of the educator and the student greatly affects the latter’s experience of the subject. “I started teaching older people, I’ve been so used to teaching company leaders. What I appreciated from these students were the straightforwardness and the ability to think in formulas. I teach in formulas: X は Y です (X wa Y desu).” Pie-sensei adds that lawyers, medicine students, and math majors usually perform well in her classes, as the skills in memorization and formal logic can easily be translated to foreign language learning.

What does her classroom look like? “I rarely use the textbook exercises. Genki, as I’ve observed, derives mainly from the Western students’ experience. I give my students the Philippine context: they are not roleplaying as Filipino exchange students in Japan, but are living the reality as Filipinos who happen to speak Japanese.” She adds that the cultural background is provided in the lessons, but she also integrates it with her personal experience in and out of Japan: “a typical example I give is the bursting of the tech bubble and how it affected day-to-day living. Japanese people were known to be generous before, but a higher degree of stinginess has been seen starting in the early 1990s.”

“‘Do you want to be a Japanese,’ I ask them, ‘or are you a Filipino learning a foreign language?’ I’ve noticed that more and more students come into beginner classes with a certain background in the language, and already have the ‘anime intonation.’ The social attitude towards otaku has also changed fairly recently. Before, it was a negative label, but now, people wear it with pride.” This is why, as Pie-sensei narrates, “proper cultural appreciation and comparison with the Philippine context is needed.” Finally, further reflecting on the current generation of students and their learning preferences, she expresses that she originally did not prefer performance-type requirements, but since it works the best in teaching the fundamentals, she has adopted it into her style. “Buti na lang magaling akong mambraso.”

More on her classes

“The student is first and foremost responsible for their own learning, but I am here to help.” It is also good to experiment and make errors, she adds. “I encourage students to make mistakes. It’s okay to make mistakes. It’s those mistakes that you remember.”

As a teacher, Pie-sensei also updates her methods, and tweaks how she handles her classes. “We have to keep with the times. An interesting thing that I have noticed is the language that the students prefer. Before–even before the pandemic, the language of instruction was mainly English, around 75 percent. Now, in explaining patterns, I use Tagalog 75 percent of the time. Even in prerog requests, students commonly use Tagalog.”

So, what do students do on their first day in a Pie-sensei class? “I request them to introduce themselves in English, and after that I ask them this: ‘why Japanese? Be honest.’ It is not really important for me to know their reasons for choosing the course, but it is necessary for them to know for themselves why they are here.”

Conclusion

We finally ask Pie-sensei what she misses the most about her first years of teaching. “I miss being the youngest learner among a table of very senior teachers. It’s where you learn and grow the most kasi eh. You learn, kahit sa tsismis.”

—

Currently, Pie-sensei teaches beginner classes, as well as Hapon 120-series courses. This second semester, she will handle one section of Hapon 10, and one section of Hapon 121. Access the “Regular Classes” and “Course Catalog” tabs of CRS for more information.

—

This article is part of the “Faculty Spotlight” series of the Department, and is also done in celebration of 100 years of Japanese language teaching in the university. Click here for more information.

Published by UP Department of Linguistics