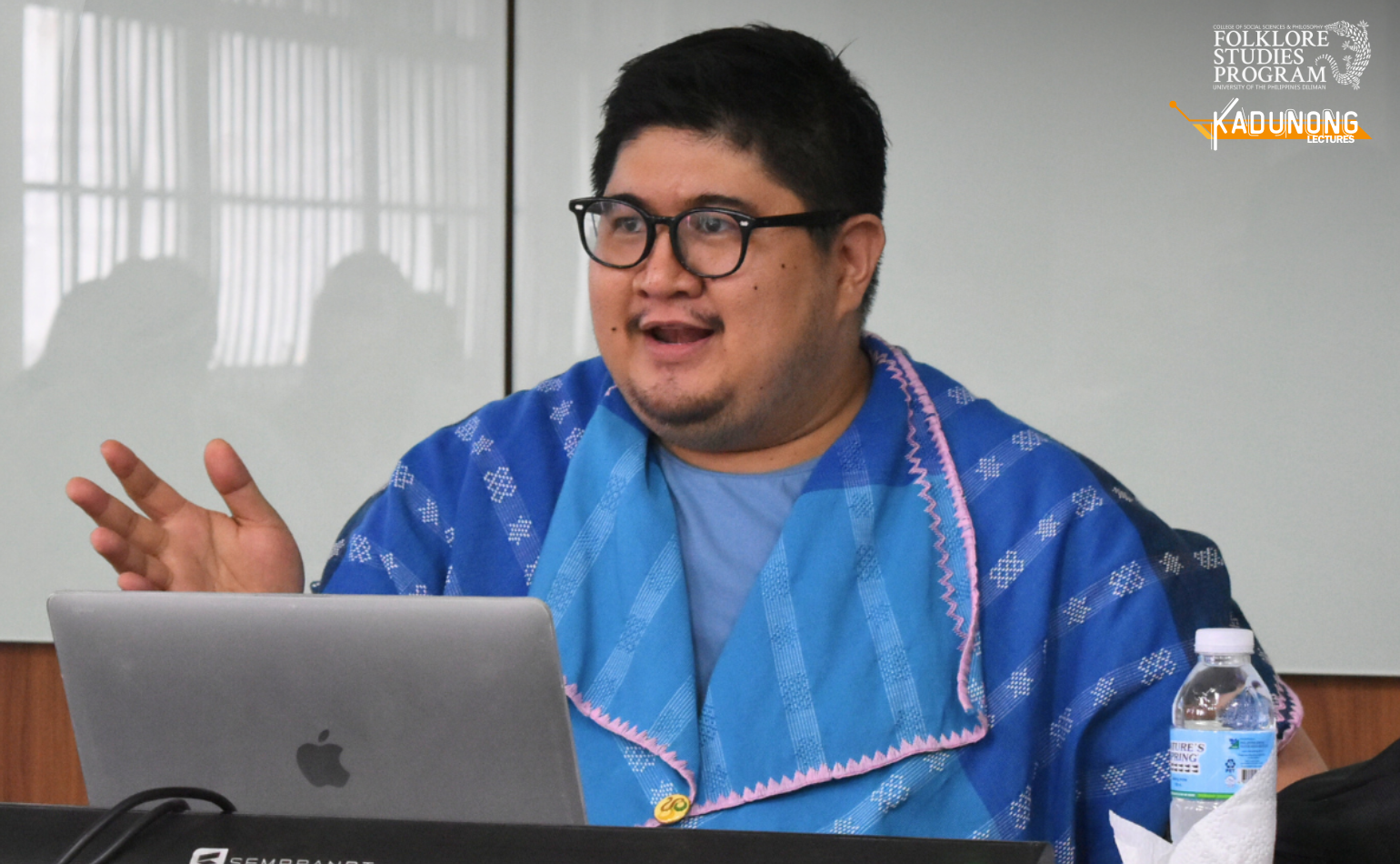

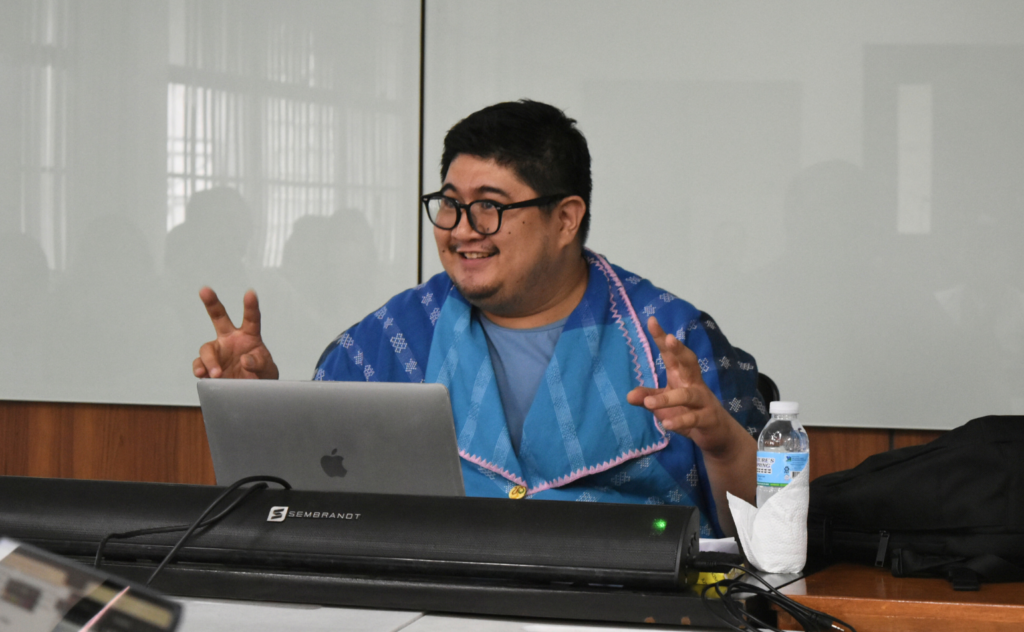

The Folklore Studies Program (FSP) of the College of Social Sciences and Philosophy (CSSP), headed by Assoc. Prof. Jesus Federico C. Hernandez, recently conducted its latest installment of Kadunong Lecture that explored the historical and sociocultural intricacies of santacruzan, an iconic procession that graces the streets of several provinces in the Philippines every May. Held last 29 May at Palma Hall Room 428, the lecture was delivered by Prof. Sir Anril P. Tiatco, performance studies expert and professor at the Department of Speech Communication and Theatre Arts (DSCTA), College of Arts and Letters (CAL).

Prof. Tiatco first explained that in accordance with several historical proclamations, the Catholic church dedicates the month of May to the Virgin Mary, hailed as the Queen of Heaven and Earth. Noting the dominance of Catholicism in the Philippines, it is not surprising that local communities enthusiastically devote time and energy to preparing for activities in her honor. In Prof. Tiatco’s words, “Ang debosyong ito at ang makulay na kapaligirang dulot ng mga bulaklak ay siyang nagbigay daan para sa pagpapatuloy ng pagtatanghal ng santacruzan o minsan tinatawag na flores de mayo.”

Known by different names in various provinces—sagalahan in Bulacan, Manila, and Bataan; dotoc in Bicol; katapusan or pag-aalay in Batangas and Laguna; and sabatan in Pampanga, santacruzan is believed to be an offshoot of Tibag, a komedya narrating the quest of Queen Helena and her court for the holy cross where Jesus Christ was crucified. This traditional play was written by an unknown author and performed in Malolos, Bulacan. Tiatco highlighted that the staged komedya now takes the form of a spectacular parade of characters that brings to life religious and folkloristic elements. Quite remarkably, participation for some equates to their display of devotion, the fulfillment of a long-standing panata.

The ensemble of characters is comprised of figures from myths and folklore, such as Reyna Banderada symbolizing Inang Bayan; culture history, such as Reyna Aetas and Reyna Mora paying homage to the indigenous Aetas or Atis of the north and the Muslim population down south, respectively; and religion, such as the queens representing the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity. Angels portrayed by young girls also parade the fifteen titles attributed to the Virgin Mary, including her designation as Reyna de Flores or the Queen of the Flowers. The procession of Marian titles is followed by the army of dose pares headed by Heneral Roldan, and finally the appearance of Reyna Helena accompanied by her son Constantino.

An interesting role which Tiatco discussed at length was that of the hermano or hermana, the one who finances and spearheads the preparations for the santacruzan. The process of selecting a hermano/a differs from province to province; in Pampanga and Nueva Ecija, for example, a fiesta committee appointed by the parish priest decides on who takes on the significant role. In San Luis, Batangas, where being a hermano/a signals the high regard a community has for an individual, a council performs the pangangatok (‘knocking’) ceremony and bequeaths the emmie (a scepter-like object) to the next hermano/a. In other communities, one can volunteer for this role. There are also cases where a family permanently works on this assignment, treating it as “a family panata” that must be fulfilled collectively. Overall, the importance ascribed by the Church and the people to the selection process not only proves how crucial this role is to the success of the event but also shows how the whole community values the annual santacruzan.

And as with many aspects of Filipino culture, the santacruzan serves meaningful purposes other than execution of a religious tradition. The parades conceptualized by the Fashion Designers Association of the Philippines in a mall in Pasay and by fashion designers in Lucena City showcase local artistry and talent. The santacruzan performed by the bakla (homesexuals) and transvestites in Marikina and in Malabon is a means to express a community’s identity. The observance of such tradition in New Orleans in the United States and in European cities such as Vienna and Brussels is a celebration of one’s heritage beyond the country’s borders. As Prof. Tiatco remarked, the nation treasures the santacruzan not only “because of its spectacular attributions but also because [of its capacity to activate] the shared values, identities and histories of communities.”

The lecture ended with an open forum, moderated by Instr. Vincent Christopher A. Santiago, where attendees recounted their own experiences in participating in a santacruzan and raised follow-up questions.

Maraming salamat po sa masayang kwentuhan, Sir Anril!

—

The Kadunong lecture series is named after Kadunong, the narrator of the Bikol epic Ibalon. The name is derived from the root word dunong, a pan-Philippine root with cognates in various Philippine languages and is reconstructed as *dunuŋ in proto-Philippine. The meaning of the word ranges from proper behavior to skill, knowledge, and wisdom. This installment of the Kadunong Lecture series was organized by members of the Department of Linguistics faculty, who also serve as affiliates of the FSP.

For updates regarding their future events, follow the Folklore Studies Program on Facebook. You might also want to read the past issues of Banwaan: The Philippine Journal of Folklore or listen to the episodes of Tuko Chronicles, the official podcast of FSP.

Published by Patricia Anne Asuncion