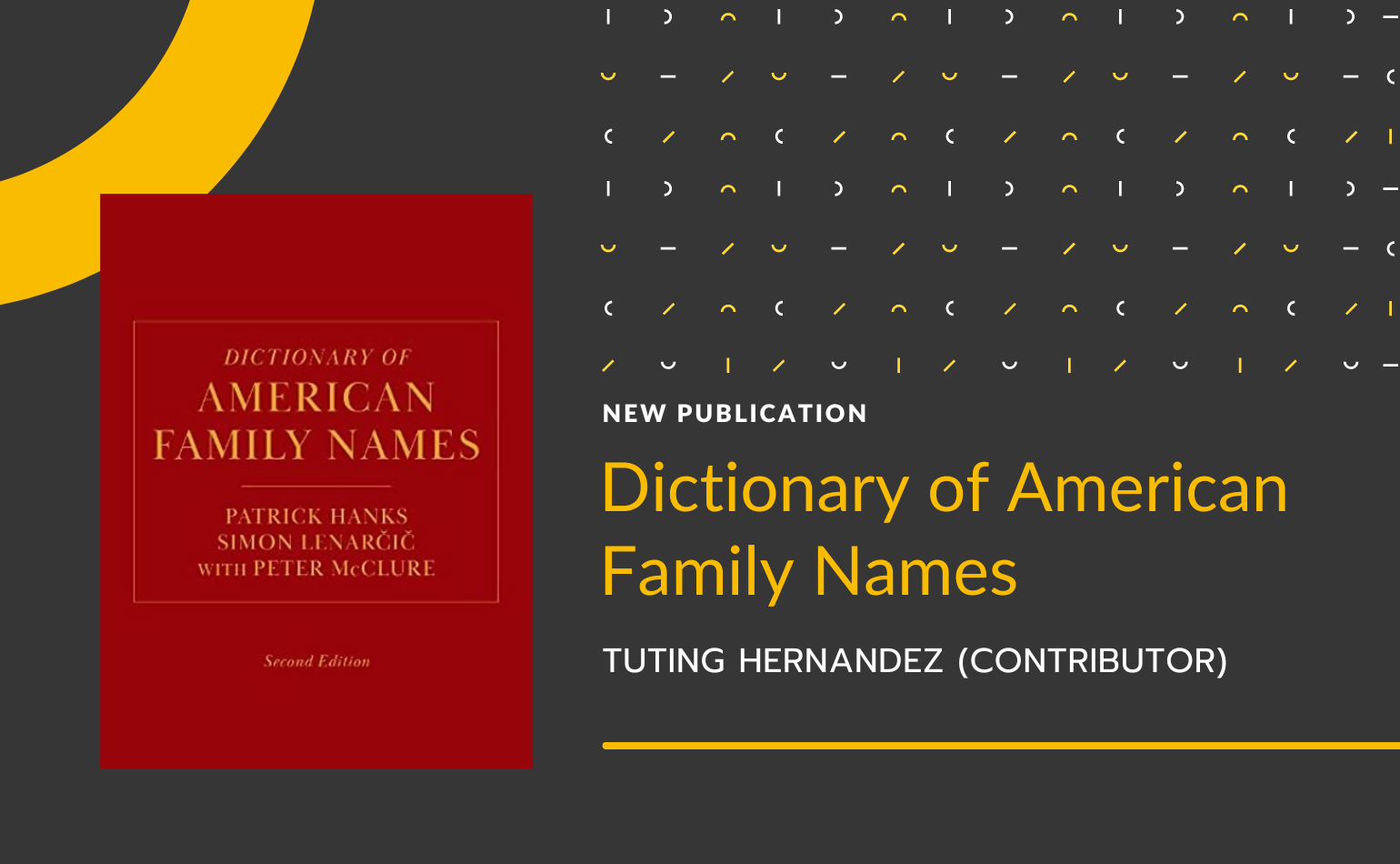

Assoc. Prof. Jesus Federico Hernandez contributed to the recently-published second edition of the Dictionary of American Family Names (Oxford University Press), compiled by Patrick Hanks (University of Wolverhampton), Simon Lenarčič (independent scholar), and Peter McClure (University of Nottingham). Hernandez is among the linguistic consultants who provided scholarly insights on surnames found in the United States. He wrote an overview of Filipino family names’ origins and histories, explaining the contact situations that influenced the adoption of foreign surnames and the indigeneity of many others.

In his overview, Hernandez explained how the 1899 US Annexation of the Philippines paved the way for the growth of the Filipino population in America. Economic, military, and educational factors throughout the course of history sustained the influx of Filipino migrants, and this diaspora is also supported by policies implemented by the US government until the present. He noted that “[t]he inclusion of Filipino surnames in the Dictionary of American Family Names acknowledges and recognizes not only the number of Filipinos in the United States but also the histories of the Manilemen [sic], the Luzonians, the agricultural workers, navy men, pensionados, nurses, health care professionals, and all the Filipino migrants and their descendants who call the United States home.”

In identifying the linguistic origins of a number of non-native names, the historical interactions that the Philippines had with other nations surfaced. The Clavería decree, imposed by governor-general Narciso Clavería in 1849, prescribed Spanish surnames eventually adopted by Filipinos. The list called Catálogo alfabético de apellidos was circulated, containing names that allude to many Filipinos’ ancestry, habitation, topography, occupation, and conversion to Christianity.

Trade with the Chinese also brought surnames that, when carefully examined, specify information regarding both the Chinese language and the area where names came from. According to Hernandez, some Chinese disyllabic and monosyllabic names also contain affixes that indicate kinship and prominence, as well as morphemes that signify positions, orders, or names of progenitors. Meanwhile, Hernandez also identified names from languages such as Arabic, Farsi, Hindi, and Sanskrit, which possibly traveled through Malaysia and Indonesia, and moved northward to the Philippines.

Likewise, indigenous surnames possess their own origin stories. Hernandez also writes about how teknonymy, or the practice of referring to a parent using the child’s name, remained prevalent despite the introduction of the patronymy, or the practice of naming a child to indicate who their parents are, in Philippine society

Hernandez also identified surnames that hint at geographic origins (e.g. the name Baguio is also the name of a city in Benguet occupied by Ibaloys. It is thought that the name is derived from the Ibaloy term bagiw ‘moss’). Filipino surnames that are derived from natural elements like flora and fauna also suggest the significance of a plant or tree in a place of origin (e.g. the ancestors of someone with the last name Narra might be from a place where such type of tree is abundant).

There are also surnames which are derived from names of occupations (e.g. Viray, from the Ilokano biray ‘large boat,’ is attributed to someone who sails or builds this type of boat). Interestingly, there are names that might refer both to the environment and the occupation of people (e.g. Pilapil ‘rice paddy’ might signify a planting field and someone who plants).

Hernandez also discussed some of the challenges that lexicographers might encounter when dealing with Filipino family names. For instance, he points out that there are roots found in surnames that vary in meaning across Philippine languages (e.g. gubat, as in the name Mangubat, could mean ‘forest or woods’ in Tagalog, or ‘to fight’ in Bikol and Visayan languages). Homonyms are also tricky since two different meanings of a word with a single form point to different source lexicons (e.g. the name Puno might either refer to a head or leader, or a woodsman). A lexicographer must also investigate structurally-complex names that bear derivational or inflectional affixes (e.g. Cabacungan, which combines the root bakung ‘a type of plant that resembles a lily,’ and the circumfix ka- -an). Additionally, there are names that undergo phonological changes resulting from affixation (e.g. the d > r alteration in Marasigan, from the root word dasig ‘lively’). And while recurring morphemes like Gat- (as in Gatmaitan, Gatchalian, and Gatdula) and Lakan- (as in Lacanilao, Lakandula, and Lakambini) can be interpreted as archaic honorifics, further investigation is required to determine the origins of the remaining components of such names.

He concluded his essay by stating that “[t]racing the origins of surnames, and deciphering the meanings contained within, uncover histories transported with these names – histories of colonization, population movements, cultural contacts, economic exchanges, formation of identities, familial lineage, cultural heritage, place-making, and production and trade. A surname indeed is like an armoire full of stories waiting to be revisited; stories that are as individual as the bearers of the surnames themselves.”

His introductory essay sheds light not only on the etymologies of Filipino names that crossed the Pacific but also on the relations, traditions, and circumstances that produced such naming practices.

Pagbati po, Sir Tuting!

Published by Patricia Anne Asuncion