How did Malay-speaking countries develop such wildly divergent language policies and ideologies? On July 25, 2023, an online lecture by Dr. Jérôme Samuel tackled just this question. Dr. Samuel, a full professor in Indonesian and Malaysian studies and Director of the Research Institute on Contemporary Southeast Asia, delivered a talk titled, “Comparing Language Policies in Malay-Speaking Countries: From Colonial Legacies to Political Will and Constraints” as part of the Department’s Talks on Asian Languages (TAL) Lecture Series. TAL serves as an avenue for the Department’s faculty, affiliates, and alumni to talk about language teaching, language acquisition, and other related topics.

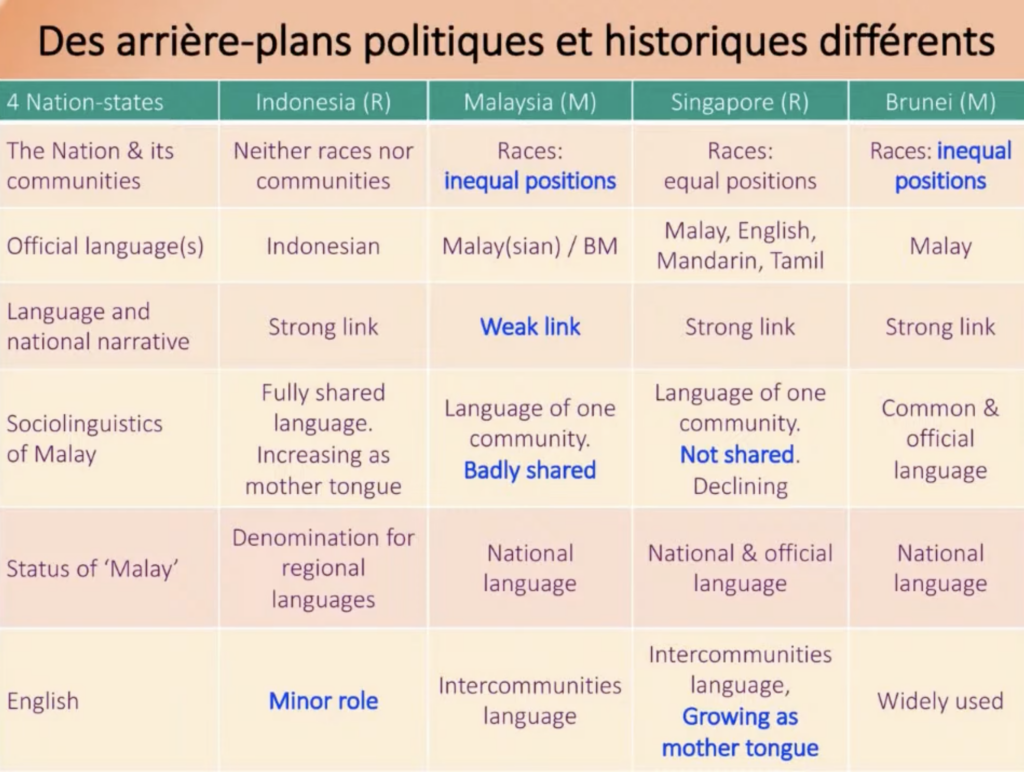

In his talk, Dr. Samuel attempted to explain “how far the legacy from the colonialists, as well as how political will and constraints in the political world have shaped the language policies in the Malay-speaking countries.” More specifically, he presented his analysis of how four countries–Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei Darussalam–diverged in their political use of the Malay language and how this informs and affirms certain state-constructed ideologies and hierarchies.

Dr. Samuel said that Malay, at some point in the histories of these countries, acted as a “second official language”, used in administration and the vernacular press during the British and Dutch colonial periods. This meant that Malay competed for use, not only against European colonial languages, but also other Asian languages like Javanese and Hokkien. Eventually, Malay was appropriated to fulfill new needs, including that of an object of study, which resulted in the creation of various dictionaries and grammars in the 19th century.

In Indonesia, Malay was built on a “strong narrative,” according to Dr. Samuel. He noted that during the early 20th century, many of the young nationalists did not speak Malay that well, having grown up with a combination of either Dutch, Javanese, or other languages. Due to its relatively ‘neutral’ status, age, and prestige, however, Malay was quickly thrust into the spotlight as a tool to maintain national unity. Dr. Samuel conjectures that what made this possible could have been a shared principle, spirit, or value that the people developed in their fight against colonialism.

Starting with the 1928 Second Youth Congress and culminating in the First Indonesian Congress of 1938, Malay was accepted by all as the language of unity and modernity. This fact, Dr. Samuel said, would come with a few questions for Indonesians such as, “What does it mean to be able speak in Indonesian? And what is a native speaker?”, particularly since it was recognized that Standard Indonesian could not be considered a mother tongue. In effect, “They [the Indonesians] are not native, not non-native, but un-native. Not native but surrounded by the language itself.”

In contrast, Dr. Samuel considers Malay in Malaysia to be a “badly shared” language. Composed of around 25 million inhabitants and with around 142 different languages, Malay or Bahasa Melayu is at the heart of the “Malay-ness” in Malaysia. During the British occupation, Dr. Samuel said the colonizers redefined “Malay-ness,” or what it means to be of the Malay race, in contrast with the identity and culture of migrants from China and India, many of whom arrived in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Post-independence, the Malaysian state would appropriate this colonial legacy by, according to Dr. Samuel, championing Malay primacy in various areas. Bahasa Melayu, which until then was the language of a single group, would become Bahasa Malaysia, the language of the entire nation. However, this narrative, Dr. Samuel says, contributed to the fragmentation of their nation, with people separated into two categories: the bumiputra or sons of the soil, composed of Malays and indigenous groups like the Orang Asli and Orang Ulu, and the non-bumiputra, which is composed of children of migrants.

Amidst these developments and the “Malayization” of education, there remain national-type schools (called Sekolah Jenis Kebangsaan or also known as “vernacular schools” in Malaysia) where Tamil or Chinese Mandarin are compulsory subjects and are used as the medium of instruction. The English language also increasingly became widespread as it served as one of the means for inter-community communication and in higher education.

Malay in Brunei Darussalam, on the other hand, was called “the language of the Sultan”. There are three major languages: the standardized Malay, which is equivalent to Bahasa Melayu; English, the language of education and administration; and the local Brunei Malay. What makes Brunei Darussalam’s case unique is the development of Bahasa Dalam, which literally means “inner language” and known as “the language of the palace”. Dr. Samuel says it is a formal, honorific variant of Malay used when speaking with the Sultan and his relatives. Despite the limited use and reach of these variants across Southeast Asia, they retain their significance in Brunei Darussalam as important markers of their rich history and cultural heritage..

Lastly, Dr. Samuel, discussed the case of Singapore, which he referred to as “the land of social engineering.” While the population composition resembles Malaysia, 60% of Singapore’s residents is of Chinese descent. While Malay occupies the symbolic role of the country’s national language, there are four official languages – Malay, English, Tamil, and Mandarin. This language policy was made to ensure communitarianism while nurturing a “balance of own versus foreign values.” There is a theoretical equivalence between all four languages, but English is commonly considered the de facto main language and lingua franca among Singaporeans of different races.

Singapore has been known for its social engineering projects. The Singaporean government initiated the ‘Speak Mandarin’ campaign in the 1970s, which is considered a success in terms of the objective of the campaign, but resulted in the younger Singaporean Chinese citizen having difficulty in communicating with older, non-Mandarin speakers and the endangerment of other Chinese languages in the island nation, such as Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese and Hakka. Likewise, the ‘Speak Good English’ movement of the 2000s, which aimed for the elimination of Singlish in favor of Standard British English, which, decades after liberation, still remained highly regarded in Singaporean society and is seen as the mark of a highly educated person. Scholars and social commentators, however, decried this act and defended Singlish as a distinctive marker of Singaporean identity. With the growing status of English, a growing portion of Singapore’s population claims it as their mother tongue. In this type of situation, Dr. Samuel asked, “how far can the state shape the language behavior of individuals and society?”

Dr. Samuel’s TAL lecture, including the subsequent highly informative Q&A session, which was moderated by assistant professors Francisco Rosario, Jr. and Dr. Jem Javier, can be viewed on our YouTube channel. Stay tuned to the Department’s social media pages for more lectures and events!

Published by Andre Encarnacion