Two back-to-back talks on the relationship between language and the natural environment were held last Saturday, 04 December 2021.

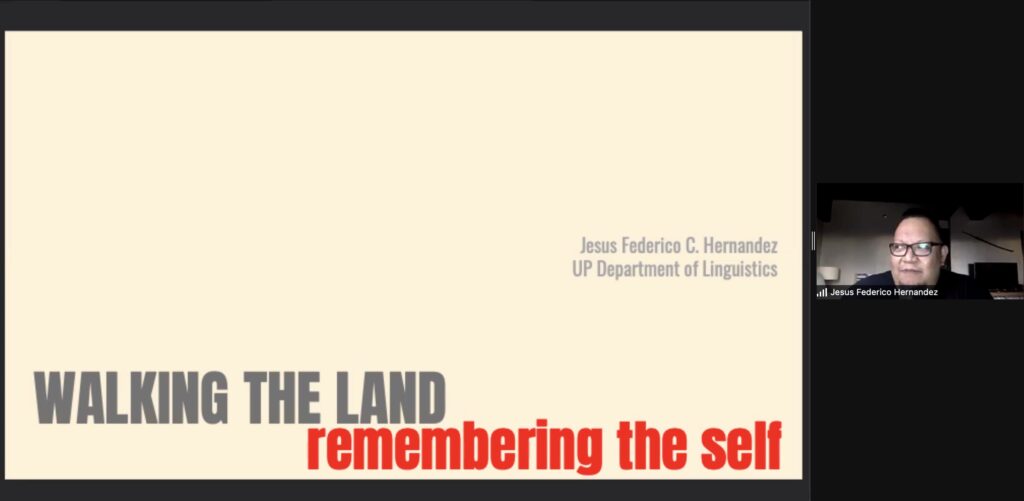

Assoc. Prof. Tuting Hernandez delivered a talk titled, “Reconstituting space: Exploring space lexicon in Philippine languages” for the UP Department of Geography’s Webbynar Series. In this talk, which aimed to provide insights into our indigenous place-marking system, he discussed lexical items that belong to the semantic domain of space, found across various Philippine ethnolinguistic groups. He demonstrated how diachronic linguistics could be used to model how our languages evolved, and how it might be used to reconstruct the cultures and worldviews of our ancestors embedded in the languages that have been passed down from generation to generation.

Among the words he discussed was the Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (PMP) term *banua, which has reflexes in many Philippine languages (e.g., banwá in Pangasinan, bánwa in Buhid, vanua in Itbayaten, and (mag)banua in Subanon). The reflexes of this term have come to refer to many things including ‘town,’ ‘community,’ ‘land,’ ‘port,’ ‘sky,’ ‘heaven,’ ‘sun,’ and ‘the underworld.’ Based on this broad range of interconnected meanings, the meaning of PMP *banua was reconstructed as ‘inhabited land, territory supporting the life of a community.’ Prof. Hernandez points out that this might reflect how we viewed elements within both our physical and spiritual cosmologies as being vital to supporting life in our communities. We can also see this in the metaphorical extensions of the term in some Oceanic languages like Tongan, Samoan, and Maori, where reflexes of *banua include the meaning of ‘placenta,’ which vividly paints a picture of our ties to the environment that gives us life.

A recording of Prof. Hernandez’s talk can be watched on UP Department of Geography’s YouTube channel.

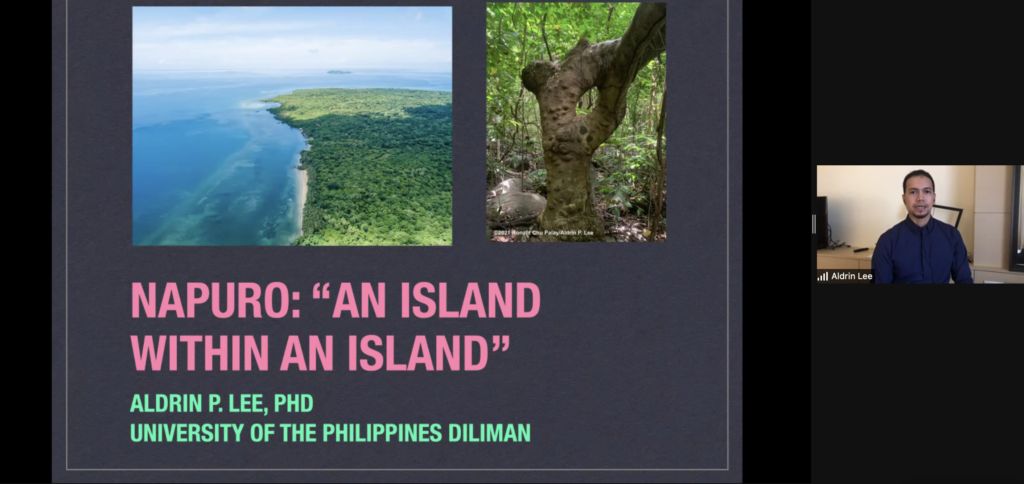

Assoc. Prof. Aldrin Lee, who is also currently the president of the Linguistic Society of the Philippines (LSP), talked about his contribution to the Living-Language-Land Project, a global nature language initiative, at the LSP’s Second Virtual Talk on Applied Linguistics (ViTAL). The event also featured the project’s creative producer, Philippa Bayley, and the creative director, Neville Gabie. The two discussed the motivations behind the project and the stories that they have so far gathered which feature words from various minority and endangered languages around the world that reflect relationships to land and nature.

Prof. Lee had written an essay for the Living-Language-Land Project on the Cuyonon word napuro, which he defines as ‘a forest that looks like an island within an island.’ In his talk last Saturday, he narrated some of his experiences from his childhood growing up in Cuyo, Palawan, and discussed how the way that he and his family used their native language to talk about various ecosystems also taught him to respect and care for nature.

His full essay on napuro can be read on the Living-Language-Land website, which also includes pictures and videos from Prof. Lee’s hometown.

Prof. Hernandez delivered the commentary on the two presentations at LSP’s webinar. He commended the project’s attempt to decolonize our thinking by providing a platform to endangered languages and the role that they play in (re)connecting people to the environment by surfacing the indigenous knowledge embodied in these languages.

He ended his commentary by delivering the following moving call to fellow linguists:

“Let me just add that beyond our academic efforts, more has to be done.

With 170 or so languages, almost a third of which are threatened, or should I say oppressed, I think having a platform such as this would offer us the necessary visibility and the documentation of some aspects of the language together with the stories, histories, signification that are attached to these words.

But still more has to be done.

The silencing of some of our languages has a direct connection to the abuse of the land. This is why I think it is important to go back to the land. Maglupa tayo. Language oppression and endangerment have always been multicausal and socio-political. One factor that stands out is development aggression. People are forcefully torn away from their lands to accommodate multinational companies and to feed the greed for money and power of the authorities. We all know the stories of mining firms stripping the land of its resources–human and linguistic resources included– and of big farms that bury not just seeds but also lives.

And linguists of the postcolony can no longer afford to sit on the fence finding comfort or hiding under the colonial bias of scientific objectivity.

We have long been severed from the collective and ancestral wisdom of the land. We also have been victims of our hubris in believing that we are the masters of our land, of our seas, often forgetting that our very selves have been cradled and nurtured by the land. Now, let us walk the land, maglupa tayo, and maybe in the process remember our selves.”

You can learn more about and make a contribution from your own languages to the Living-Language-Land Project by visiting their website living-language-land.org.

Published by UP Department of Linguistics