As the tenth installment of the 2025 Philippine Indigenous Languages Lecture Series (PILLS) and as part of the 2025 Linggo ng Kolehiyo ng Agham Panlipunan at Pilosopiya Celebration, Professor Aldrin P. Lee presented his study on Cuyonon (ISO 639-3 [cyo]), titled “The Cuyonon Lexicon for the Intertidal Zone: From TUBÓG (Tide Pool) to ATÓL (Stone Tidal Weir).” This lecture was held at Pilar Herrera Hall last 24 October 2025.

The lecture built upon Prof. Lee’s earlier work on island linguistics in the Philippines and focuses on the systematic documentation of the Cuyonon lexicon associated with the intertidal zone, a transitional zone between the sea and land that is submerged during high tide and exposed during low tide. Focusing on Cuyonon, an island language spoken primarily in the Cuyo Islands, where the intertidal system surrounds landmass and plays a critical role in food security, mobility, and community life. The study aims to provide a novel description of the stone tidal weir using an indigenous ontological framework, despite stone tidal weirs having been long documented in various parts of the world, including some areas in the Philippines, such as Panay Island, as previously discussed in Anthropologist Cynthia Zayas’ work: Stone Tidal Weirs Rising from the Ruins (2019).

Lee opened the discussion with a brief introduction to his upbringing in an island environment, situating the discussion within his lived experience and building his vocabulary, which reflects a deep connection with the sea, and how he is rooted in this environment. The introduction illustrates how everyday language use reflects sustained interaction with the sea. From this, Lee describes the intertidal zone as not only a marine ecosystem but also an important boundary marker, a gauge for the tidal range, and a buffer zone that protects the landmass from the deep sea. This explains why the intertidal system and the human activities carried out in the zone significantly contribute to the linguistic system and the languages spoken in the islands.

Island Linguistics and the Intertidal Zone

Within the framework of island linguistics, the intertidal system contributes to the shaping of linguistic structure. The lecture emphasized theneed to account for the linguistic systems unique to small island environments and the necessity of developing language elicitation materials suitable for languages on islands.

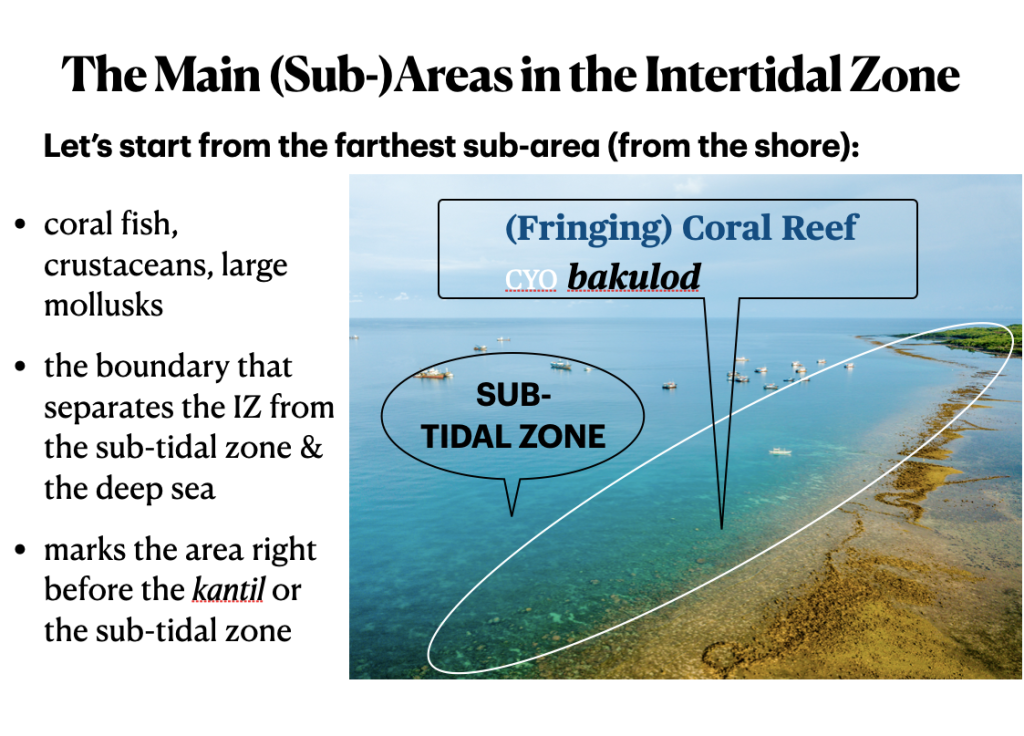

The lecture proceeded with a systematic discussion of Cuyonon terms for the intertidal zone, starting from the farthest sub-area from the shore. At the outer boundary that separates the intertidal zone from the subtidal zone and the deep sea lies bakulód, a home to a wide variety of coral fish, crustaceans, and large mollusks. Bakulód also marks the area right before the kantil ‘sub-tidal zone’, an area recognized as a zone of heightened risk due to sudden changes in depth and with stronger waves.

The low intertidal zone is divided into kakulapwán and napgás. Kakulapwán is a vegetated area dominated by kulapo ‘sea grass’, the root word of Kakulapwán. kulapo is strongly attached to rocky substrates and supports a range of fish species. Napgás, by contrast, is composed of coral rubble, mainly consisting of small rocks, dead corals, and the skeletons of small animals.

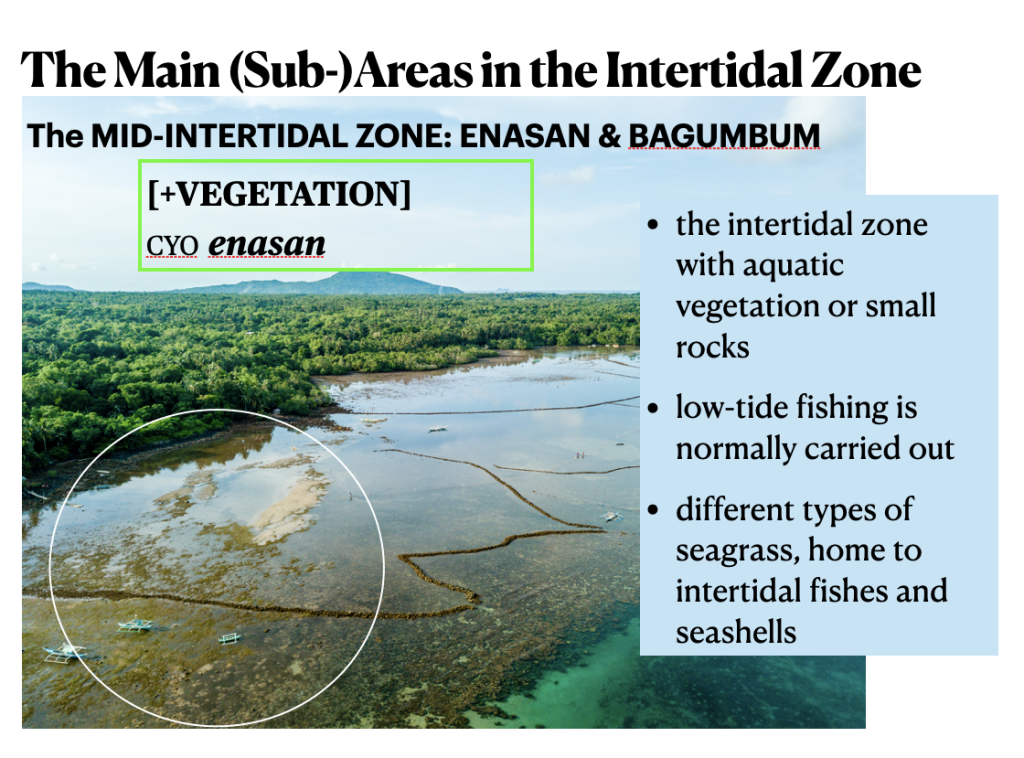

The mid-intertidal zone is further subdivided into: enasán, referring specifically to vegetated intertidal areas, and bagumbon, the non-vegetated area commonly used for leisure activities, such as swimming, and an area where boats can be anchored.

Closer to the shoreline are the high intertidal zone classified as either ˆ and limaw-limaw. Tubóg is a relatively larger vegetated area in the high intertidal zone, featuring a “garden-like” ecosystem filled with seagrass and small rocks. It is where there are larger tide pools that retain seawater during low tide, where fishers go to find edible small marine organisms. On the other hand, limaw-limaw is the smaller and sandier tide pool with less vegetation. Immediately along the shoreline is the kabatwán, where a cluster of beach rocks is found, serving as habitats for specific shellfish and fish species.

Directional Verbs

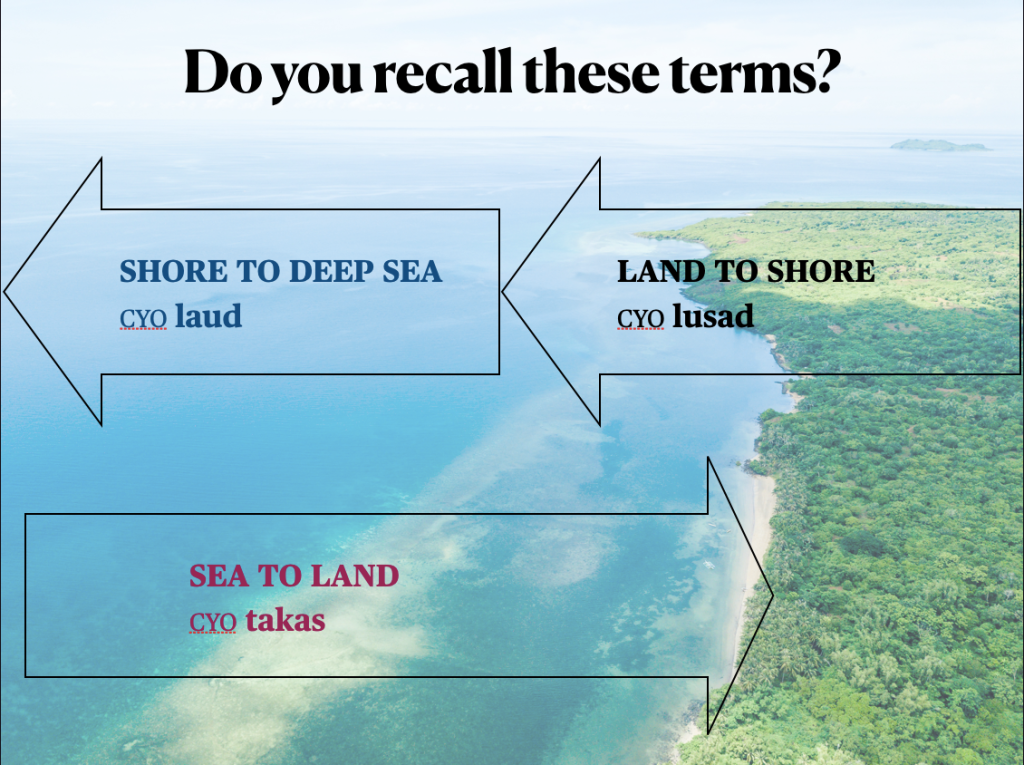

The lecture also highlighted directional verbs for movements across land and sea. Lusad denotes the movement from the land to the shore. While laud is the movement from shore to the deep sea. Lastly, takas refers to the movement from land to sea.

Intertidal Activities and Practices

A substantial part of the lexicon pertains to fishing activities based on tidal range and time. The island’s resource-rich intertidal system serves as the basis for the lexicalized forms associated with the zone’s activities. The terms for high-tide fishing vary according to the methods and/or the tidal range of the activity. This includes eyey, which refers to walking or staying in the intertidal zone when the sea level is around the waistline. In this activity, fishing is permitted, except for swimming. Alternatively, eseb is the term used when swimming, diving, or spearfishing.

Low-tide fishing during daytime is called pakinás, while panulo refers to the nighttime low-tide fishing. Communal fishing activities during low-tide daytime fishing are reflected in terms like panlamnek and pamakasla, both referring to methods of stunning fish (without killing them) to make them easier to catch. Panalubang is a popular fishing activity, typically conducted at low tide at nighttime, where fishers use a long spear. Certain animals that are only caught at night are called surulon, indicating the association with lamplight during nocturnal fishing, as sulo literally means ‘to be lit by lamp’, as lamp or sulo is necessary in this fishing method. This activity is usually carried out around the new moon phase.

The Cuyonon lexicon also includes verbs and adjectives for the skill-based aspects of fishing, such as mata which refers to the act of ‘spotting’ certain sea animals, gem which means the act of catching fish using bare hands, lukad, an act of extracting some burrowing sea creatures from the sand, and maelak, which describes a situation where the fish is hard to catch under certain conditions.

Atól: Stone Tidal Weirs

One of the distinct practices in Cuyo Island is the practice of building a “fort-like” stone wall structure called atól at the outer edge of the intertidal zone right before the coral reef formation in the subtidal zone, which is normally far from the shoreline. Its purpose is to catch sea animals that are not found in the intertidal zone. The stone wall structure enclosing a central pool called bunoan is made to attract aquatic animals that normally do not swim in the intertidal zone during the low tide. This area retains water during low tide, trapping the sea animals that entered during high tide. This ensures easy catch for the manig-atol ‘owner of the atól’. The Atól also serves multiple purposes: facilitating fishing, acts as a tidal indicator, and serves as a barrier against strong waves.

There are also other lexical terms related to atól, such as terms for ownership (manig-atól), and clusters of atól (kaatólan).

Lee also highlighted that the practice of atól is now declining due to the labor-intensive nature and reduced interest among younger generations. It raises concerns about the potential loss of both the practice and the associated lexical knowledge.

Broader Implications and Concluding Remarks

The intertidal ecosystem of Cuyo Island has profoundly shaped the Cuyonon lexicon. There are still knowledge systems encoded in this lexicon that remain underdocumented or are inadequately captured by existing linguistic tools.

“Linguists will not be able to stop the language from dying if the natural ecosystem that shapes and enriches the language’s lexicon has already died,” emphasized Lee while also highlighting that scientists from different disciplines should be working together to save what we currently have.

Lee also hopes that this work will draw the attention of the young generation on Cuyo Island to study their language and culture, and ensure that sustainable knowledge systems live on and are passed on to future generations.

During the open forum, Lee used the lecture as a platform to articulate a political-economic critique of language shift and ecological decline in Cuyo, emphasizing the role of commercial fishing interests, urban-centered development aspirations, and persistent failures of state accountability. He stated that the younger Cuyonons’ reduced engagement in farming and fishing is because of the normalization of leaving the island for Manila or the “urban capitalized dream of being in the city” where economic opportunities are highly valued than island-based livelihoods.

He acknowledges that Cuyonon is an island language, shaped by its ecological environment, and may not easily flourish outside its community; its maintenance outside the island context may be particularly difficult, despite active efforts to sustain its use. He further noted that parents exercise significant influence over children’s language learning, and homogenized aspirations and restrictive language policies, such as the “English Only Policy,” further threaten linguistic and epistemic diversity.

Most importantly, Lee also identified two major sources of pressure on subsistence fishing: destructive commercial practices such as dynamite and cyanide fishing, and large fishing corporations whose vessels repeatedly damage coral reefs. This prolonged economic dependence on corporations owned by politically prominent families. Lee directly called on politicians to be held accountable, condemning continued entry of commercial vessels into municipal waters and urging strict enforcement of the proposed fifteen-kilometer boundary (Kinse Kilometro Para sa Mangingisdang Pilipino Act), which he argued is routinely undermined by political protection of corporate interests.

The recording of Prof. Aldrin Lee’s lecture is now available on the Department’s official YouTube channel. The next installment of the 2025 PILLS was delivered by Prof. Mary Ann Bacolod on November. Follow our social media pages and stay tuned for the release of the next PILLS articles and recordings

Published by Jenica Frances Estrellado