The Linguistics 290 class of Assoc. Prof. Aldrin P. Lee, PhD (UP Department of Linguistics) organized a webinar on the “Current Trends in Linguistics,” which was livestreamed on the department’s Facebook page via Zoom last 12 January 2024, from 4:00 to 6:00 PM. The event is part of the final requirement of the class, which aims to be a response to the dynamicity of linguistics as a field of inquiry. “[Lingg 290]…seeks to identify and understand the current trends that have emerged in the Philippine context,” Dr. Lee said in his introduction.

The webinar featured the lectures of Dr. Arran Stibbe from the University of Gloucestershire for ecolinguistics, and Department Chairperson Dr. Maria Kristina S. Gallego for language contact.

Ecolinguistics: The search for new stories to live by

“Some people are linguists, some people are ecologists,” Stibbe, Professor of Ecolinguistics, opened as he explained the core thesis of ecolinguistics. Borrowing from his training at the Centre for Human Ecology in Scotland and at the graduate school for linguistics at the Lancaster University, he explained that the two fields provide perspectives in the analysis of stories, and could help in the preservation of the environment. “But why do we need new stories to live by? And this is where we are going to need to have a look at ecology […] It’s really good […] to cover both sides of things [linguistics and ecology].”

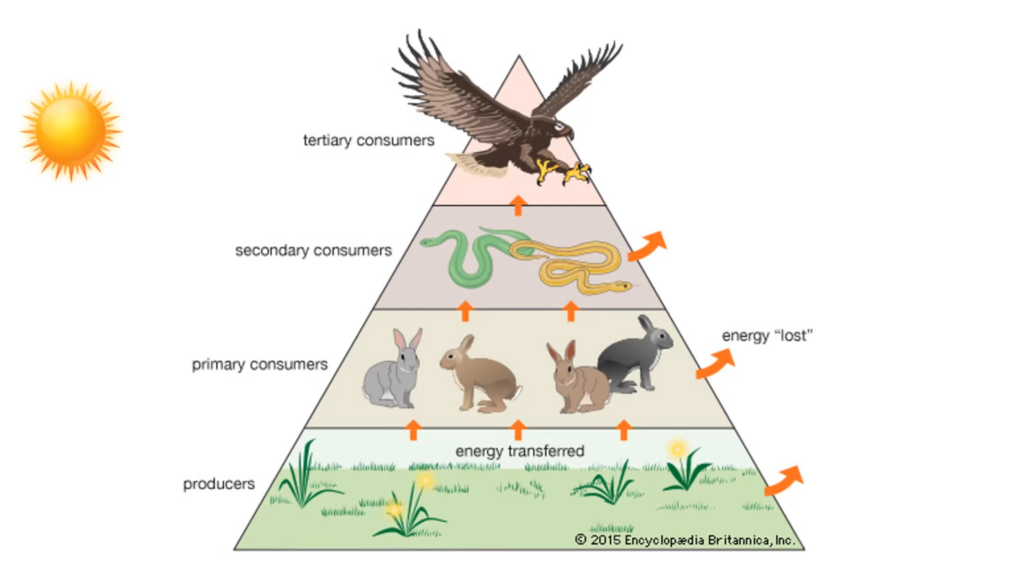

The energy pyramid, which Stibbe described as the typical form of ecology taught in schools, could be seen as inaccurate. “We’ve been told that something is wrong about this form of ecology,” he added. In the typical model, the plans are producers, and there are several levels of consumers. However, humans and livestock make up most of the biomass, having a total of about 160,000,000 tons, compared to the combined nine million tons of biomass of wild birds and mammals. Because of this, the sun, which is usually presented in textbooks as the only source of energy, becomes insufficient. Fossil fuels are then ‘farmed’ to account for this imbalance. This of course leads to carbon dioxide emissions, which now has to be reduced via a drastic change to keep the increase of world temperatures to manageable levels.

Massive change into a sustainable civilization must then be made to move away from what Stibbe suggested is an ‘industrial, consumerist and unsustainable’ system. To achieve this, he quoted Nigerian novelist Ben Okri in saying that “stories are the secret reservoir of values.”

Stories and the ecolinguist

An ecolinguist must reveal the stories that we live by, according to Stibbe, as these shape our cultures. They must then question the collected text from an ecological perspective, and if it proves to be unsustainable, replace it with stories from traditional cultures which originated from a time with no fossil fuels. “[We must] tell new stories about who we are as humans, [and] about the way the word is.”

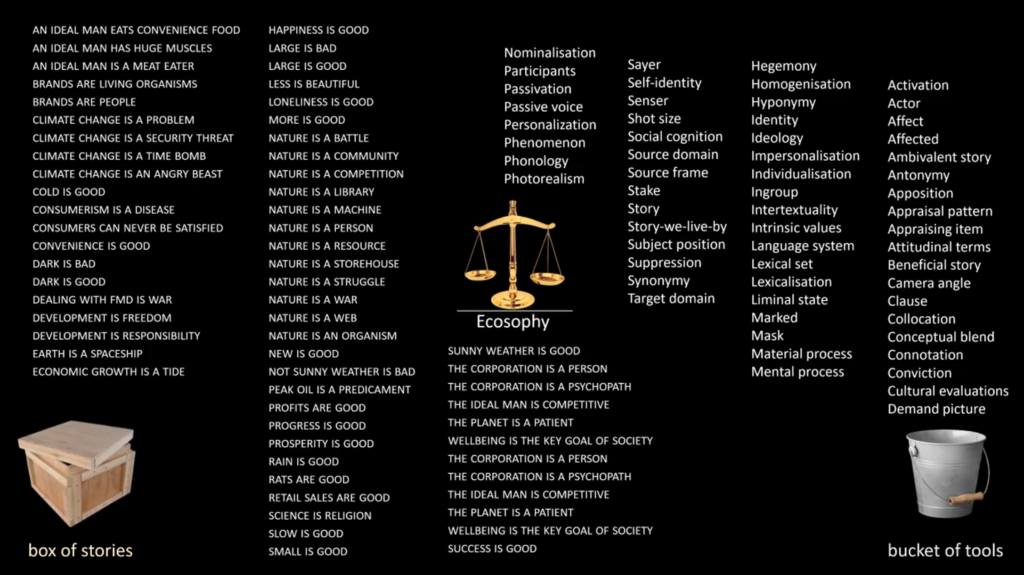

News reports and advertisements are possible sources of these damaging texts. For example, the use of terms like slumping, dragged down, steep decline, confusion, disappointing, plummeted and fears in describing the decrease in the sales of diesel cars supports the idea of humans as being ‘fundamentally selfish.’ Low retail sales of these products are appraised as bad, which then becomes deeply embedded in the minds of individual people and in the Western cultures as a whole. This ‘more is better than less’ behavior then carves a negative impact in the world through fossil fuel use and greenhouse gas emissions.

This narrative, however ingrained in society, is at its core artificial. As Stibbe said, “it’s not describing the world–it’s creating the world,” as people are not naturally greedy; it is advertising that creates that reality.

He also presented other several harmful stories found in media, which included (i) the ‘dual depiction’ of items being responsible for happiness instead of the filial connection that it represents, (ii) meat (whose production and logistics are both ecologically destructive because of methane) as becoming a symbol of the national identity of the United States, (iii) nature as being boring compared to plastic toys, and (iv) pigs being treated as machines through the use of terms like structurally sound, boar power and sow breakdown.

“Ecology is usually presented in the language of economics,” Stibbe said as he finished his discussion on the bad stories in society. The role of the ecolinguist then is to successfully find and spread new stories which contradict the ‘lessons’ of the former.

A fascination in nature

An old pond

a frog leaps in

sound of the water

This haiku by the Japanese Edo period poet Mastuo Bashō was used by Stibbe in arguing that old stories can be utilized to influence how we see and treat the world. According to him, during his stay in Japan, his experience of hiking up a mountain drastically changed into being that of fascination in the slow beauty of nature after he read the short poem. “We,” he said, “are part of a group that includes more than just humans. The story here is that nature is worthy of attention.”

He tied all of his discussions to the context of the Philippines by saying that our traditional cultures hold traditional ecological wisdom which could help in the preservation and restoration of nature. Protecting language diversity then becomes even more important as the life of the language, its speakers, its non-speakers and the environment are all at stake. But where and how can we start? Stibbe suggested one step:

“Start with some texts in your everyday life that have made you angry–or [those which] have made you inspired.”

A summary of the different stories and ‘ecosophies’

Language contact: Perspectives

“Contact has been increasingly recognized as an intrinsic part of language,” Gallego said as she introduced the phenomenon. As it covers a large scope in the study and features of languages, “[it becomes] relevant to different subdisciplines of linguistics such as psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics, language acquisition, as well as language change.” However, the field of language contact remains fragmented, as it lacks a unified theoretical or methodological framework.

The individual

Gallego highlighted the fact that in many communities across the world, multilingualism is the norm: “it is very rare to find a monolingual speaker.” In the case of the Philippines, a person speaks at least three languages on average, which is usually made up of (i) their mother tongue, (ii) the regional lingua franca and (iii) the national language, Filipino. English is also taught, learned and spoken in school as it is one of the languages of instruction. As people from different groups with different linguistic backgrounds commonly interact with each other, it is inevitable for language contact to occur.

In the presentation, the phenomenon has been defined as that which arises when “individuals using two or more languages at the same time and at the same place” engage. This then results in hierarchies, with one or more languages having an influence on the others.

The language user acts as the central agent of change, and as the locus of contact as they are the ones who introduce innovations. The role of the study of language contact, then, is to investigate and understand the links between the speakers, the factors and mechanisms driving change, and the linguistic outcomes arising as a result of the phenomenon.

According to Gallego, we start by analyzing the different contact outcomes—the linguistic innovations themselves. Different linguistic materials have varying degrees of transferability: as it has been observed, nouns are more transferable than verbs, derivation is more common than inflection, and lexical materials are said to be more easily innovated than grammatical ones. Therefore, materials that are more stable in terms of linguistic structuredness, frequency of new additions and cognitive processing are less transferable. However, Campbell (1993) presented some counterexamples in some languages like Samaraccan, Takia and Bolivian Quechua. This is why a purely linguistic and structural approach to the study of language contact is inadequate, and a contact-dependent method which takes into account social scenarios is needed.

The community

“The kinds of variation observed among the language use of bilingual individuals comprise potential change that can be propagated across the community,” Gallego said. Thomason and Kaufman (1988) discussed the different social factors affecting language change, and described the nuances differentiating them. In language maintenance, native speakers typically incorporate foreign features such as vocabulary into their language. Meanwhile, in cases of language shift, there is a portion of the population consisting of speakers who have learned the recipient language–but imperfectly. “With the so-called ‘errors’ that they made in learning the recipient language,” she added, “becoming incorporated into the language.”

Part of Thomason and Kaufman (1998)’s framework is the notion of intensity of contact, which is a variable that is relevant both in contexts of maintenance and shift. As Gallego explained, the social contexts that underlie this intensity are different in the two situations. In the case of the former, the length of contact between the two groups as well as the degree of bilingualism of the recipient language speakers are relevant. In the case of shift, meanwhile, the size of the shifting group and their level of bilingualism are important.

The case of Babuyan Claro

The Babuyan Claro community belongs to the Babuyan group of islands in Cagayan, with its residents typically being able to speak around three languages. Their L1 is Ibatan, the local language of Babuyan Claro. It is closely related to the Batanic languages, which include Ivatan.

Next, the people also speak Ilokano, as it is the regional lingua franca of the Babuyan group of islands as well as northern Luzon. They are also proficient in Filipino, and learn English in school.

Gallego emphasized the significant effects of other languages in Ibatan, which has been driven by several sociolinguistic factors. “Ilokano has been a major player in the development of Ibatan not only as the main language in contact with it, and the main source of contact-induced change in the language, but also in terms of its vitality.” For a long time, Ibatan has been threatened by the position of Ilokano within the bigger region, but Babuyan Claro’s changing socio-political landscape also reshapes its language ecology.

The village center, which was a domain for the use of Ilokano before, is now predominantly a location where people also speak Ibatan. Next, there was also a shift in the dominant religion of the community from Catholicism (where Ilokano served as the main language in religious activities) to Protestantism where Ibatan is the main language. Also, in terms of education, the Ibatan were originally forced to take their schooling (from Grade 4 onwards) on the Ilokano-speaking island of Calayan, where they experienced instances of discrimination based on their ethnicity. Now, because an integrated school was established in Babuyan Claro, the students do not have to leave the island anymore–leading to less contact with Ilokano in this domain.

Meanwhile, increased geographic mobility of the speakers of Ibatan enabled them to be in frequent contact with other linguistic communities in mainland Luzon. Because of this new location’s prior experience in linguistic and ethnic diversity, the Ibatan speakers experience less discrimination.

All of these factors then have overt linguistic effects. For example, older generations report to having higher proficiency in the regional lingua franca, but younger speakers exhibit higher preference to Filipino as being their second language. In one example of individual-level cross-linguistic influence, Gallego presented an elicited sentence from a non-dominant speaker, highlighting the linker (LK) or relativizer. For Ibatan, the form of the LK is a. However, in the collected Ibatan sentence, the speaker uses the Ilokano LK nga consistently.

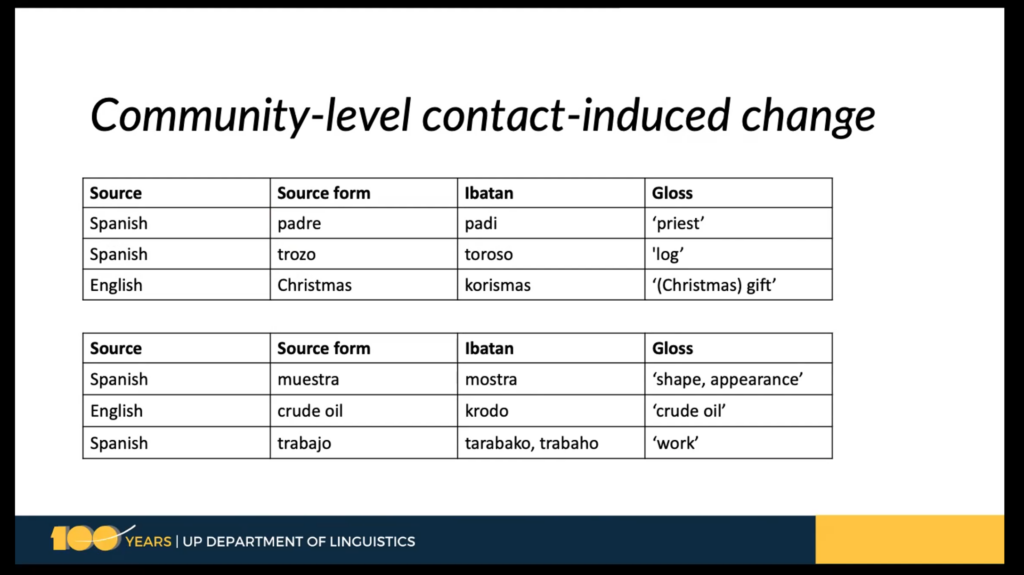

Next, for community-level contact-induced change, consonant clusters were initially not permitted in the phonotactics of Ibatan. As an example, the Spanish words padre ‘priest’ and trozo ‘log’ were borrowed into Ibatan as padi and toroso, respectively. However, recently, words like mostra ‘shape, appearance,’ krodo ‘crude oil’ and trabaho ‘work’ have been observed in the language.

Contact and change

“It is not yet clear how exactly multitude of factors interact to drive change,” Gallego said as she closes her lecture. Psycho- and sociolinguistic mechanisms in both the individual and community levels drive change, but the degree and method of entanglement have not yet been determined.

For the case of Babuyan Claro, the structure of the social network is relevant in shaping language use and ideologies. Also, marriage patterns have been seen as a significant factor. Finally, the traditional linguistic variables of age and gender appear to be specially important, as well. Still, as Gallego points out, more research must still be done. “There is still much to know about multilingualism and the nature of language contact.”

Bringing the discussion back to the general context of Philippine languages, as the country is one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world, Gallego said, it is important to uncover the contexts of language contact in both small-scale multilingual communities and in wide-scale locations. “A language exists always in relation to another language […] We tend to speak in the same way as the people we interact with.”

Congratulations to Dr. Lee’s Linguistics 290 class for successfully organizing this webinar! Stay tuned for the department’s next events, which will be announced here at the website and our social media pages.

Published by UP Department of Linguistics