Paglulunsad at Paglalayag brought together scholars, students, and guests in an event that both answers a call to raise awareness regarding the global linguistic situation and fulfills the Department’s commitment to preserve and promote Philippine languages and dialects. The program, moderated by Inst. Vincent Christopher Santiago, was held on November 22 at the Palma Hall Second Floor Lobby. A recording of Paglulunsad at Paglalayag is now available on the Department’s YouTube channel.

In his welcome remarks, project coordinator Asst. Prof. Jem R. Javier explained why this event is significant. Paglulunsad at Paglalayag is the first in-person activity of the Department since 2020 when the pandemic began, and it is also held in celebration of the Department’s centennial anniversary. Javier says that the projects presented at the event attest to the significant growth and progress of the Department. Ultimately, it also shows the Department’s solidarity with the International Decade of Indigenous Languages (IDIL) and its belief that “[a]s any fundamental right of a human being, linguistic right is essential, and as such, should be respected and honored by everyone at all times.”

Javier’s welcome remarks was followed by a message from Dr. Bec Strating, the Director of La Trobe Asia. She briefly introduced what La Trobe Asia does and how it supports various research and advocacies.

Dr. Gerald Roche (La Trobe University) presented the policy brief titled “Indigenous Language Rights and the Politics of Fear in Asia,” co-authored with Dr. Madoka Hammine (Meio University) and Assoc. Prof. Jesus Federico Hernandez (University of the Philippines Diliman).

He started by establishing the connection between issues of indigenous languages and the concept of human rights, and remarked that indigenous peoples are over-represented in two areas: linguistic diversity and endangerment and state-sponsored killings. Building up on this idea, he said that it is important to recognize that documenting, archiving, and attempting to revitalize languages comprise only a part of the answer to the issue of endangerment. He emphasized that there is a need for “political space for indigenous and minoritized communities to act” on resources that they are sometimes deprived of or barred access from. In order for this to happen, Roche says that we have to critically examine “the political relations and arrangements that are driving [people] to move from their languages to national [or] regionally dominant languages.” We therefore have to look at these issues using the framework of language oppression or “the coerced loss of language.”

Roche then acknowledged that a powerful form of resistance to language oppression is the assertion of human rights, more specifically language rights. Aside from those implicitly protected in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (e.g. right to non-discrimination, freedom of association), there are also rights that pertain to language itself as stipulated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (e.g. right to mother tongue education, to revitalize the language). However, there are some places where it is the state which serves as the perpetrator of the oppression of minorities by targeting human rights activists and imposing sanctions against activism and advocacy work.

Roche shared his personal experiences while working in Tibet as a scholar and an advocate of linguistic diversity and rights. He recounted the period when people demanded education in their own language and how this movement was gradually suppressed by the government. He observed that the lack of resistance to such state-sponsored crackdowns was not due to the people’s lack of grievance but because of repression by political forces through what they described in their policy brief as “insidious programs and coercive assimilatory policies that […] erode and erase languages and identities of minority nationalities.”

To end, two of the recommendations that the team formulated to address the issues discussed were mentioned. First is the production of a report regarding indigenous rights and indigenous language rights defenders by the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders. Second is the creation of a working group within the organizational committee of the IDIL tasked to “provide recommendations to indigenous activists about how to protect themselves legally [and] physically, [and how] to engage in this activism in a way that will not place them at risk […].”

Comments and questions raised during the open forum were about language death and alternative terminologies; the hegemony of the standard Tibetan language and the Chinese government’s assimilation policy; and language reclamation efforts outside the classrooms.

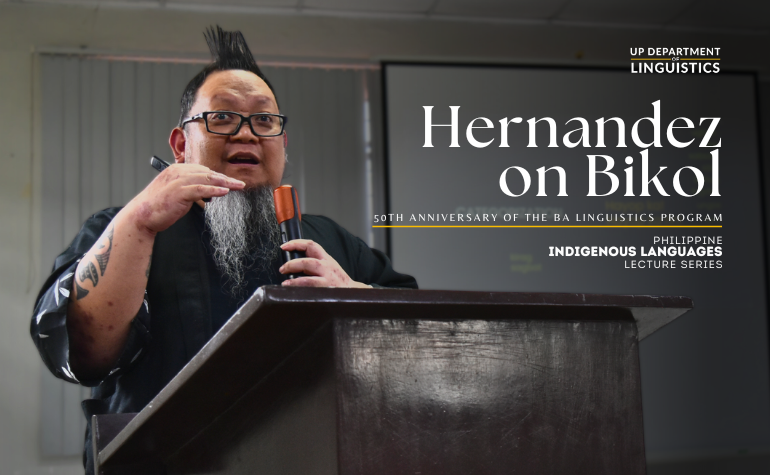

The Katig Collective, an initiative headed by Assoc. Prof. Tuting Hernandez, was also officially launched at the event. The Katig Collective primarily aims to raise awareness regarding the country’s languages and the communities that use them. Teaching associate John Michael Vincent De Pano and research assistant Patricia Anne Asuncion presented a brief overview of the initiative’s mission, activities, and future plans.

They provided a sketch of the linguistic situation in the Philippines, including the background against which language endangerment transpires. It was pointed out that extra-linguistic causes such as the country’s multi-colonial experiences, political and social oppression, displacement, and extreme poverty comprise a “system that promotes inequality and social injustice” and that this “continues to interfere with the ways of life and rights of many ethnolinguistic groups, including the liberty to use their languages.”

A tour of the initiative’s official website was also conducted, and the guests were shown how to access the site’s maps, language capsules, and other information which students, educators, and enthusiasts can consult and use for their own research. As for future endeavors, De Pano and Asuncion shared that The Katig Collective plans to write articles, organize discussion groups, and collaborate with organizations and volunteers in projects related to addressing language endangerment and advocating for language rights.

For the third portion of the program, assistant professor and current chair of the Department Maria Kristina Gallego shared stories drawn from her fieldwork and research, focusing on how people came to live on Babuyan Claro and changes in the community’s language ecology and attitudes.

Gallego discussed how the locals maintain a distinction between groups based on where they reside on the island: mixed Ibatan-Ilokano families mostly occupy laod (‘west’), while “pure” Ibatans reside in daya (‘east’). Despite the ethnolinguistic lines drawn between the communities, Gallego pointed out that “egalitarian multilingualism resulted in the emergence of Ibatan and coexistence with Ilokano during Babuyan Claro’s initial years.”

A shift in language preference is also an important characteristic of the island. The 1970s saw the rise of Ilokano due to the island’s administrative integration into the municipality of Calayan whose lingua franca is Ilokano. Religious activities and educational instruction were in Ilokano, and Ibatan speakers experienced discrimination in the municipal center. However, in the 1980s, several social activities and development projects paved the way for the empowerment of the members of the Ibatan community. More recent developments such as the awarding of a certificate of ancestral domain title in 2007 and the opening of a high school in 2004 and a senior high school in 2016 “have reshaped and continue to reshape the linguistic repertoires of the people of the island.”

Gallego also recounted the opinions and attitudes of “pure” Ibatans and Ilokano-speaking migrants towards the language which gave her insights on what speakers consider “proper” or “crooked” and on the dynamism and fluidity of their concept of identity. Towards the end of her presentation, she remarked that “despite these many experiences, many Ibatan today still maintain the use of their language even during their time outside Babuyan Claro” and that “[t]hey see their use of Ibatan as a secret code, as an advantage, and they take multilingualism as their weapon despite the ongoing marginalization of the Ibatan community.”

The program ended with a series of lively cultural performances from Kontra-GaPi (Kontemporaryong Gamelan Pilipino), the resident ethnic music and dance ensemble of the UP College of Arts and Letters.

The Department would like to thank everyone who participated in this event. Please look forward to future in-person and virtual activities of the Department as we continue to celebrate our centennial anniversary!

Published by Patricia Anne Asuncion