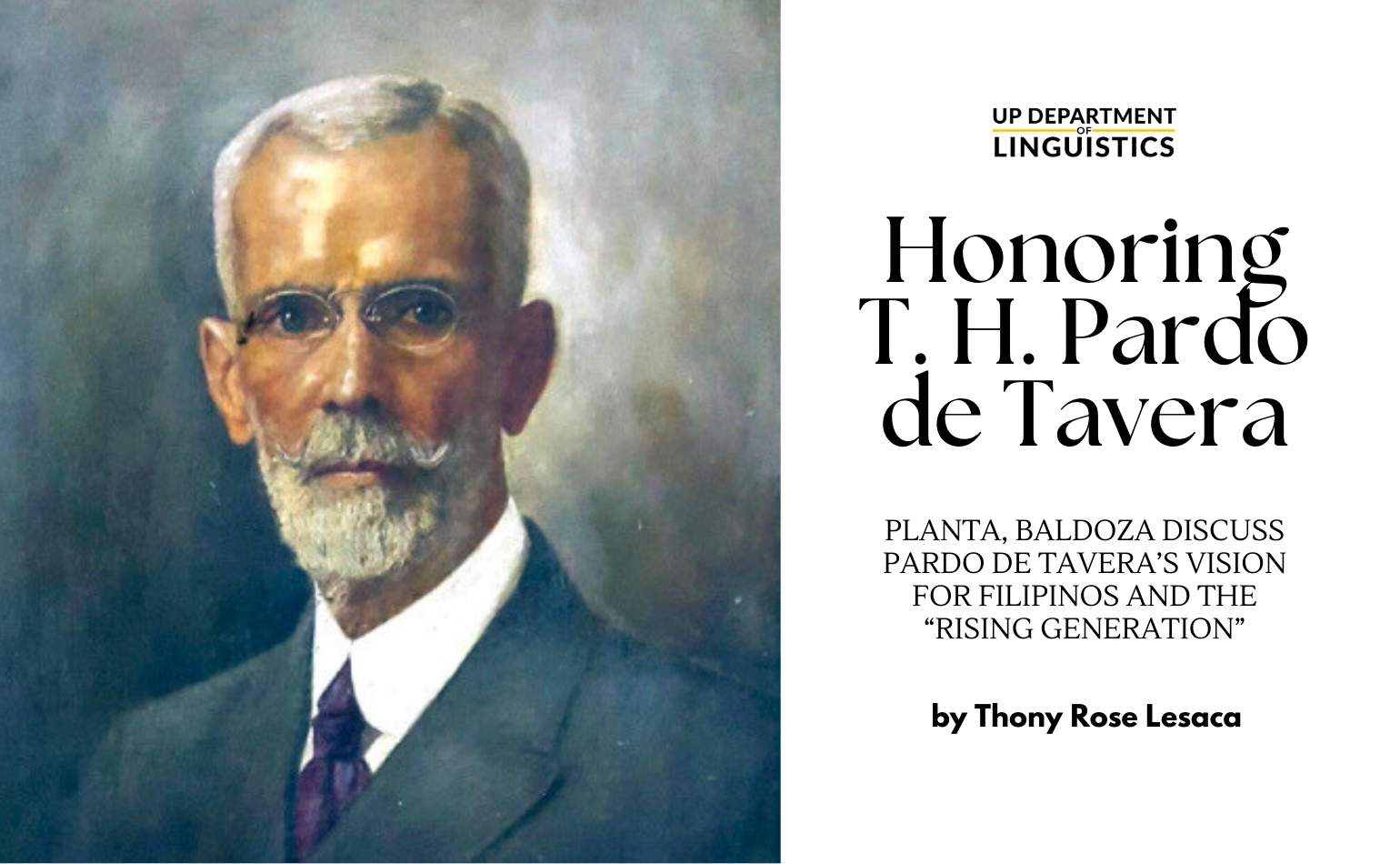

In commemoration of Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera’s 100th death anniversary last 26 March, the Department featured back-to-back lectures by Dr. Ma. Mercedes Planta, professor from UP Department of History, and Jonathan Victor Baldoza, PhD candidate of History at Princeton University. The two lectures focused on Pardo de Tavera’s legacy through his vision for the Filipinos and engagement with the “rising generation” of his time.

Pardo de Tavera was a linguist whose intellectual scholarship contributed to the foundation of linguistic education in the Philippines. He served as the Department’s inaugural chair in 1923 when it was still known as the UP Department of Oriental Languages.

Planta, in her lecture entitled “All for the Philippines: Education, Knowledge and Labor in T.H. Pardo de Tavera’s Vision of Self-determination and a Stronger Filipino Nation,” explored the early life and works of the Philippines’ foremost intellectual.

Born in an illustrious family of lawyers, Pardo de Tavera was a doctor who had many interests with his works spanning several topics. His contributions to 19th and 20th century intellectual scholarship include; Biblioteca Filipina (1903) which contained 2,850 entries on the history, ethnography, linguistics, botany, zoology, history of publishing, and bibliography in the Philippines; his discovery of Fr. Plasencia’s Las Costumbres de los Tagalos en Filipinas (1892) which contained notes about the customs and laws of the Tagalogs; and his commentary on the Pedro Murillo Vellarde Map (1734).

Planta highlighted that Pardo de Tavera’s writings about the Spaniards were very impartial despite being considered as a filibuster. One manifestation of this was his historical account in the Census of the Philippine Islands: Taken under the Direction of the Philippine Commission in the Year 1903 that described how influential the friars were and how fractured the Spanish government really was.

Pardo de Tavera in his work, as cited by Planta, said, “history makes the friars responsible for the errors committed by the Spanish Government in these islands, but it would appear that without the aid of the religious orders it would have been impossible for Spain to have fulfilled, even to the extent she has, her promises of civilizing the Filipinos and of helping them to advance along the lines marked out by the European nations.”

It was to this extent that the friars ruled over the Philippines for 208 years, which in Pardo de Tavera’s observations, perpetrated ignorance among Filipinos in shaping their future towards progress and self-determination.

“For Pardo de Tavera, the most important obstacle to Filipino people and to the Filipino nation was the kind of education that predominated the country. It was not that it was only religious, it was the fact that it perpetuated a period of ignorantism,” Planta explained.

“Pardo de Tavera expressed that when the Spaniards came, the rationale for religious education was to win us from our superstitions, from all sorts of things because we are people with no institutionalized religion. But when the Christian doctrine or Christianity was brought to the Philippines, instead of winning out our own superstitious beliefs, it actually supplanted those superstitions with other kinds of superstitions. But this time, under the guise of Catholicism.”

At the time, the only solution he saw for the Philippines to achieve self-governance was under American colonial rule. This pro-American stance earned Pardo de Tavera a lot of criticism. However, it was in his own words that he refuted such critics saying, “I have not accepted American sovereignty for the pleasure of being under the domination of a foreign nation, but because I thought that such was necessary to educate us in self-government.”

Planta emphasized that for Pardo de Tavera, the Philippines’ true independence requires a strong intellectual and cultural foundation. It was not just about rejecting foreign rule but it was more crucial to create a nation that can stand on its own intellectually, economically and politically.

“Pardo de Tavera’s vision for the Philippines is deeply tied to a sense of Filipino identity. He believed that the Filipino people had a unique national character which had been forged through their historical experiences, particularly under Spanish rule,” she concluded.

In the second lecture entitled ”T.H. Pardo de Tavera and the ‘Rising Generation’,” Baldoza explored the period leading up to the intellectual’s death in 1925. It was during this period that Pardo de Tavera engaged more with younger Filipinos known as the “rising generation.”

Baldoza defined the “rising generation” as Filipinos that were educated in American colonial schools. During this time, Pardo de Tavera witnessed the advancement of co-education where women were recognized, English was the lingua franca, and a period where the sciences were advancing.

It was what Pardo de Tavera described as the modern and progressive education of the Filipinos that involved “the acquisition of knowledge of truth through experiments, through an acquaintance with real and positive facts.”

Two prominent figures from this generation include Encarnacion Alzona and Cecilio Lopez. Alzona, a champion of women’s rights, had directly received a letter from Pardo de Tavera in August 1919. He urged her to write about the social history of Manila. Lopez, the first trained Filipino linguist, followed the scientific outlines of genuine Philippine orthography laid down by Pardo de Tavera and Dr. Jose Rizal with the usage of k in his paper about a Tagalog variant in Marinduque.

“Like Tavera, Lopez and Alzona embodied the empirical state of mind, in a way positioning themselves as bringers of progress and modernity through science through their scholarship in history and linguistics,” said Baldoza.

This progress allowed Filipinos to slowly detach from Spanish scholarship towards a new direction full of possibilities. However, critics like Teodoro Kalaw and Renato Constantino argued that this “rising generation” became too Americanized and led to the miseducation of Filipinos. Constantino, in particular, termed this generation as “captive minds” with captive ideas.

Baldoza refuted this by explaining that, “While the rising generation indeed had a distinctive culture and appearance that may seem more American than Filipino, many important issues concerned them whether they were doctors, lawyers, scientists, social scientists. They took active roles on questions of women’s suffrage, political independence, social welfare, and cultural nationalism.”

He argued that these scholars strived to contextualize and provide a broader framework that appropriately met the needs for progress in the Philippines. Moreover, it was through Pardo de Tavera’s engagement and influence among these young scholars that his commitment to Philippine affairs was known to be ironclad.

Pardo de Tavera’s advocacy for an enlightened FIlipino public opinion materialized with young Filipino scholars. “It illustrated an aspiration to rationality and modernity but also revealed a kind of transformative change in outlook and perspective, in how they were able to ponder their history, culture and identity,” Baldoza remarked.

Pardo de Tavera’s online exhibit may be visited at <thefirstchair.squarespace.com>. The recording of Dr. Mercedes Planta’s lecture is available on the Department’s YouTube channel. Planta’s book, Traditional Medicine in the Colonial Philippines, 16th to the 19th Century, which won “Best Book in Science” at the 37th National Book Awards for Best Books Published in the Philippines, is available for sale at the University of the Philippines Press.

Published by Thony Rose Lesaca