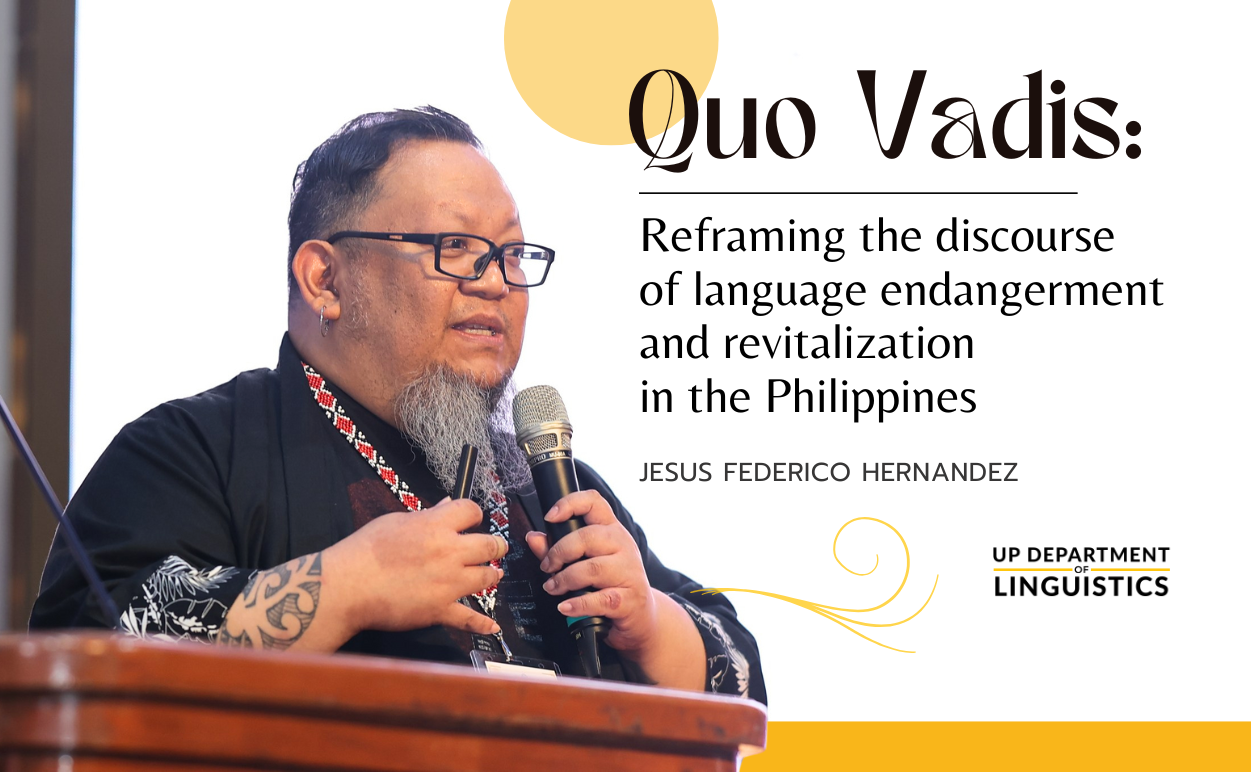

Assoc. Prof. Jesus Federico C. Hernandez delivered the final plenary lecture, “Quo Vadis? Reframing the discourse of language endangerment and revitalization in the Philippines,” during the 2nd International Conference on Language Endangerment (ICLE) held last 11 October at the Philippine Normal University (PNU).

Where to start?

As an entry point, Assoc. Prof. Hernandez posed the question, “Where do we start talking about language endangerment?” He began by describing a timeline of relevant developments, among which are the panel discussion held during the Linguistic Society of America’s (LSA) annual meeting in 1991, and the subsequent release of an article in the journal Language regarding the global crisis in 1992. In the Philippine context, among the pioneering works are Ernesto Constantino’s contribution to the Endangered Languages of the Pacific Rim (2001–2003), and two articles by foreign scholars focusing on the vitality of select Philippine languages (Headland, 2003; Anderson & Anderson, 2007). The list of milestones also includes the UNESCO proclamations for the years 2008, 2019, and 2022–2023 which recognize and celebrate the languages around the world. However, amidst all the institutional initiatives and academic activities related to language documentation, description, and revitalization during the past five to seven years, Hernandez pointed out the need to evaluate such a course of action. “Maybe it’s time for us to stop and think, to pause and interrogate what we’ve been doing. […] Ano nga ba ito para sa atin?”

He proceeded by explaining that the majority of efforts are directed towards safeguarding diversity, which equates to preserving linguistic patterns and types, knowledge and worldviews, and culture for posterity through documentation and archiving. Such an approach to dealing with languages, unfortunately, results in the exclusion of speakers and, by extension, the generation of disembodied voices. Moreover, the idea of preserving and saving languages becomes problematic when languages are viewed mainly as artifacts devoid of their natural dynamism and fluidity. Preference for preserved languages also perpetuates negative attitudes towards language change. And, inevitably, the idea of “saving” awakens the messianic tendencies and egos of researchers.

A crucial change witnessed in recent times is the active involvement of communities in documentation and revitalization projects. However, as Hernandez remarked, “These are palliative measures [that only] address the symptoms but not the cause.”

It’s complicated

Apart from usual practices, Hernandez also problematized the abstract concept of “killer languages,” which serves as a convenient means of framing language endangerment in the country through pitting languages against each other (e.g. Filipino versus another Philippine language). Resorting to such a narrative obscures the fact that there are actually people, policies, and extralinguistic factors that contribute to the detriment of indigenous languages and the communities that speak them.

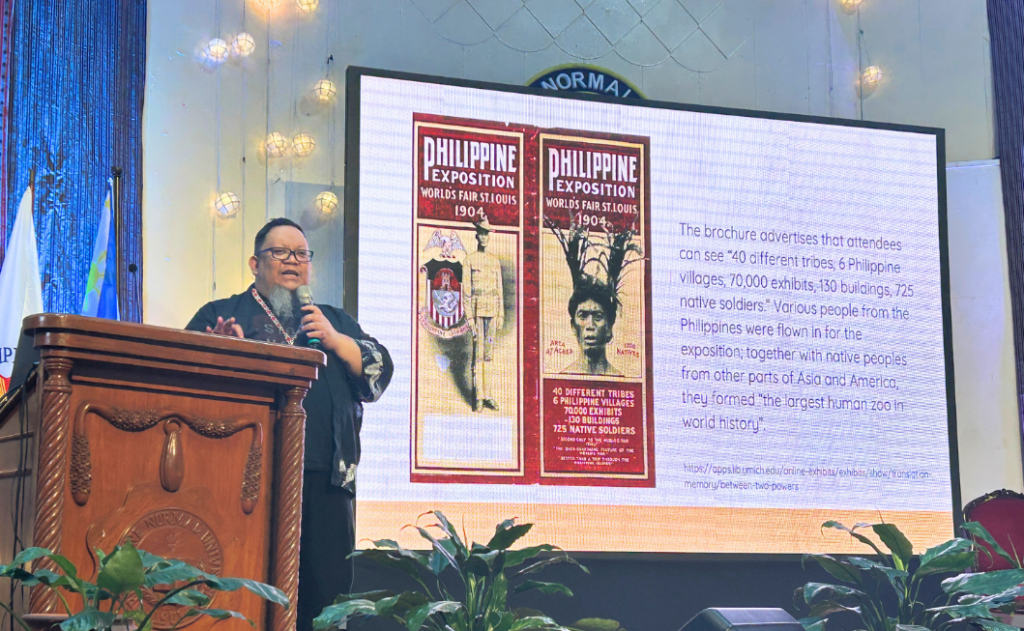

Hernandez illustrated the multicausality of language death in the Philippines by expounding on four primary factors. First is the trauma brought upon by the nation’s multicolonial experience under Spanish (1565–1898) and American (1898–1946) rule, which propagated the notion of local languages being substandard in contrast with the colonizers’ tongues hailed as prestige languages. Second, in conjunction with multicolonial trauma is the linguicide perpetuated by political and socio-cultural policies such as those in the education sector. Third, the displacement of communities due to the militarization in the countryside and the violent intrusion of extractive industries. And, finally, poverty which renders communities vulnerable to abrupt changes, including the realities associated with migrating to urban centers. All these factors contribute to the eventual degradation and devaluation of both languages and ethnolinguistic identity, leading to the idea that “the story of language endangerment is a story of oppression.” Hernandez also noted the futility of documentation and revitalization efforts if these issues remain unaddressed.

Quo vadis?

Citing political anthropologist Gerald Roche, Hernandez echoed the “need to shift terminologies—from language death and language revitalization to language oppression and language reclamation” as a step to recognizing and emphasizing the political dimension of this matter. He insisted that this endeavor should not stop in revitalization, highlighting that “it has to go towards reclamation [of languages and rights]; reformation [of policies]; and restoration [of human dignity].” He also characterized the linguist of the post-colony as someone who “cannot hide behind the pseudo-objectivity of science” and be indifferent to the struggle of the people.

Ultimately, Assoc. Prof. Hernandez reminded the audience of the need to organize, build networks, and forge bonds that advocate language rights and linguistic justice.

In hindsight, this lecture is an invitation to stakeholders to reassess not only their understanding of language endangerment but also their practices, motivations, and possible contributions to directing change, both in the discourse and in our people’s lived experiences.

[Photos from the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (KWF)]

Published by Patricia Anne Asuncion