World Yodel Day, a worldwide celebration of the rare art of yodeling, is held yearly on August 8. This date was chosen since the four circles in 8/8 suggest the shape of the mouth when it makes the rounded [o]-[u] sounds of yodeling (Yodel Day, 2021). It is also the name of the organization holding the event, which had been founded in 2013 by Korean yodeler, Peter Lim.

This year, the event was held fully online in the form of a series of YouTube videos, released in sequence throughout said day. It opened with the premiere of the Tagalog rendition of the theme song, “Araw ng Yodel,” translated and sung by Filipina yodeler, gossamery. This was followed by a video compilation of renowned yodelers from several countries sharing the reasons behind their love for yodeling.

gossamery participated again in the next segment: a remake project of the Austrian yodel song, “Dorf Jodler,” which was originally released by Rudi Meixner in the 60’s. The video shows the six yodelers from six countries (Korea, Indonesia, China, the Philippines, the U.K., and the U.S.A.), reinterpreting the song in their own languages, and in their own lyrical and musical styles. Then came the premiere of “When You Sing Yodel,” a production consisting of interviews and a music video, made by the yodeling community in China.

The half-day event then concluded with “Dorf Jodler all over the World“, an exclusive Zoom forum where the yodelers from the six countries who participated in the Dorf Jodler remake project (except Korea) shared the stories behind their original lyrics. This was attended by several yodel enthusiasts from China and the Philippines. As the host as well as one of the performers, gossamery explained that the lyrics of her rendition, “Yodel ng Tahanan,” was inspired by the plight of OFWs. The whole event was recorded and will be released on the Yodel Day YouTube channel.

As gossamery herself, I am thankful for the significance of the opportunities that this event has offered; not only as a singer-songwriter and performer, but also as a student of linguistics. “The Philippines’ #yodelingg student musician,” now a habitual affixation to my screen name, is a title that I can gladly claim.

The lingg in #yodelingg

Yodeling is a vocal technique that involves sudden transitions between chest to head voice and, usually, lexically meaningless syllables (Wey & Metzig, 2021). According to musicologist Timothy Wise, there is also the ‘stylised yodel’, which refers to yodeling syllables of words. Either way, however, the intentional break in the voice is most important in the general understanding of the term (Wise, 2007). Another common characteristic is the exaggeration of this break (Warren, 2017).

The material that I’ve picked up from three years’ worth of Lingg classes colors my experiences as a singer in many ways, but this fact has never been more tangible than in yodeling. My understanding of linguistic concepts in fact helped me gain confidence in the activity in a relatively short time, and is a big factor as to why I appreciate it so much.

I officially started to yodel after my freshman year–after we had covered basic phonetics in Lingg 110. Most of my observations in yodeling concern articulatory phonetics: physiological production of the different phones, the building blocks of the sounds made in the vocal tract. In terms of acoustic phonetics, on the other hand, the sonority hierarchy of speech sounds is relevant. Of course, yodeling takes acoustics beyond phonetics, what with the alterations between chest and head registers–between pitch and quality of the voice itself.

I myself like to think of yodeling as a back-and-forth motion of contact between parts of the tongue and the roof of the mouth, complemented by the exaggerated breaks between chest and head voice. It’s a physical activity, a dance; it is an acrobatic performance by the members of the vocal tract. But unlike the dancing of the body, it produces–rather than reacts to–the music.

“But first, to master those yodels…”

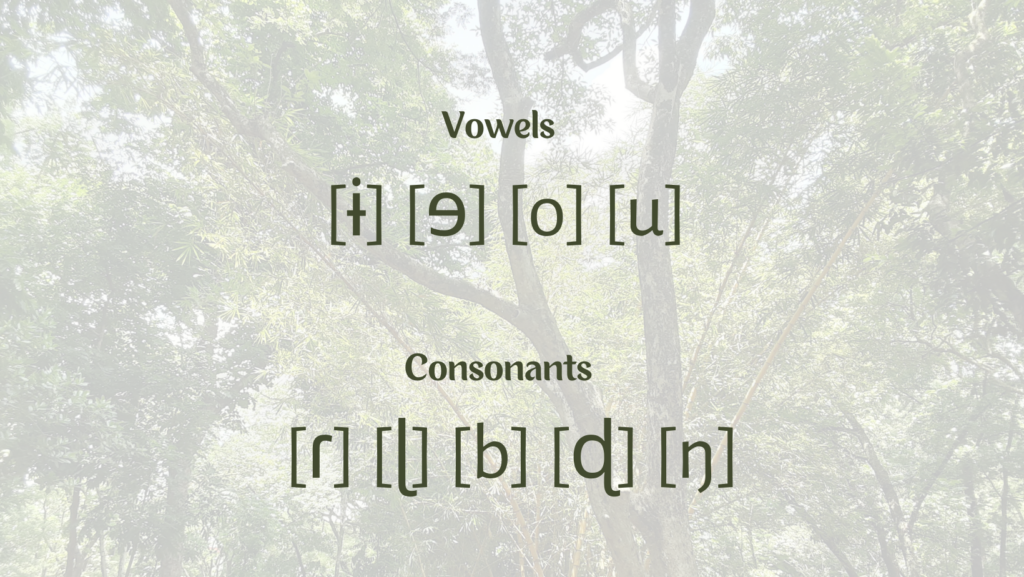

Tongue position is relevant in the transitioning between the chest and head registers. In a phonetic sense, this would be the distinction between high and low vowels. That is, it is common in yodeling for a change in tongue position (and thus, a change in the vowel) to accompany the jump in register. For example, from the lower (chest voice) to the higher (head voice) pitch, the complementary vowel transition is usually [e] to [i], and [o] to [u]. Higher tongue, higher pitch, and a shift in quality–physiology and acoustics work hand in hand. I find that the simultaneous movement in different muscles of the vocal tract makes the shift easier, especially when done rapidly.

On the other hand, yodeling patterns, my own included, also forego alternating vowels along with the voice breaks. As a result, the break is exaggerated beautifully, although it requires more effort from the larynx. Again, tongue position is crucial here: I noticed that it is only effective if it is a high vowel that is maintained. This must be because the high vowels are more tense, i.e., made with relatively greater restriction in the vocal tract (O’Grady & Archibald, 2015). It’s a smaller opening; thus, the sound waves are more concentrated (with stronger vibrations in my head and nasal cavity). And, the greater the concentration of the sound in both chest and head register, the greater the exaggeration of the voice break.

Consonants, on the other hand, play a role in tonguing, the rapid transitions between syllables (Leuthold, 1981, as cited in Wey & Metzig, 2021). Sonority of course plays a part here as well. Voiced consonants, such as plosives, nasals, and liquids are primarily used, and fricatives are rare, if they are used at all. The word ‘yodeling’ itself–very much an onomatopoeic utterance as well–is a glide, a stop, a liquid, and a nasal, all strung together by vowels. Tonguing, then, is basically an excited onrush of sonorous speech sounds.

While I was still getting the hang of the yodel, I found my familiarization with the consonants of other languages to be a great help. I could more easily identify the sounds yodelers use. In the case of consonants, some of these sounded more sonorous than the ones to which my tongue was accustomed to. For instance, Melanie Oesch, a popular Swiss yodeler, uses a sound similar to [ɖ], which is present in Bengali (Mandal et al., 2011), and it has become a staple in my yodel. With the tongue in the postalveolar area unlike the [d] of English, there is more space inside my mouth; thus, more resonance.

Notice the opposite approaches towards vowels and consonants in yodeling–vowels, being more sonorous, are constricted; while consonants, naturally lower in sonority, are amplified. This attempt to balance their amplitudes must then result in overall sonic coherence. When these sounds alternate, along with the change in qualities of the head and chest registers, the result is both an auditory and articulatory treat (as well as an intellectual one in my case, with the IPA chart within reach).

“Araw na Yodel” or “Araw ng Yodel”?

Upon Peter Lim’s request, the first half of the song is actually in English, like some of the previous versions in other languages. Furthermore, he also said that I could write original lyrics for this part, which I did for its second stanza.

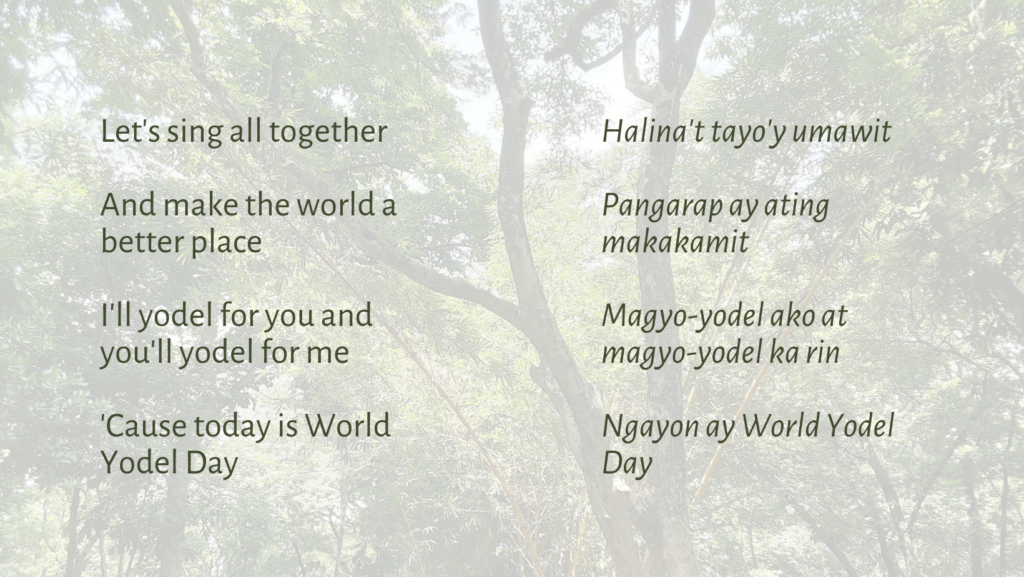

The first Tagalog stanza was really intended to be a translation of its English counterpart. The English lyrics are modified from those of Francelle Doiron, the Canadian yodeler who sang the theme song in 2016; and LayDee KinMee, the Australian yodeler who translated its first English version, from Korean.

As may be seen, all lines but the second are semantically equivalent. I had difficulty translating its idea into Tagalog, more so in a way that would conform to the melodic and syllabic constraints present. Thus, I settled with yet another modified line, from Doiron’s “Let’s dream new dreams” (2016).

Then, as with the second English stanza, the second stanza of Tagalog had a more original flavor:

Since Tagalog is not my first language, I felt the need to consult with a native speaker–in this case, my mother–to check for errors and inconsistencies. One particular bit which had the both of us thinking hard was the Tagalog bridge: “Bawat watawat iwawagayway.” We considered whether to stick to the imperative of the English, or to use the added syllable of the contemplative aspect, which flowed better in the melody. We chose the latter.

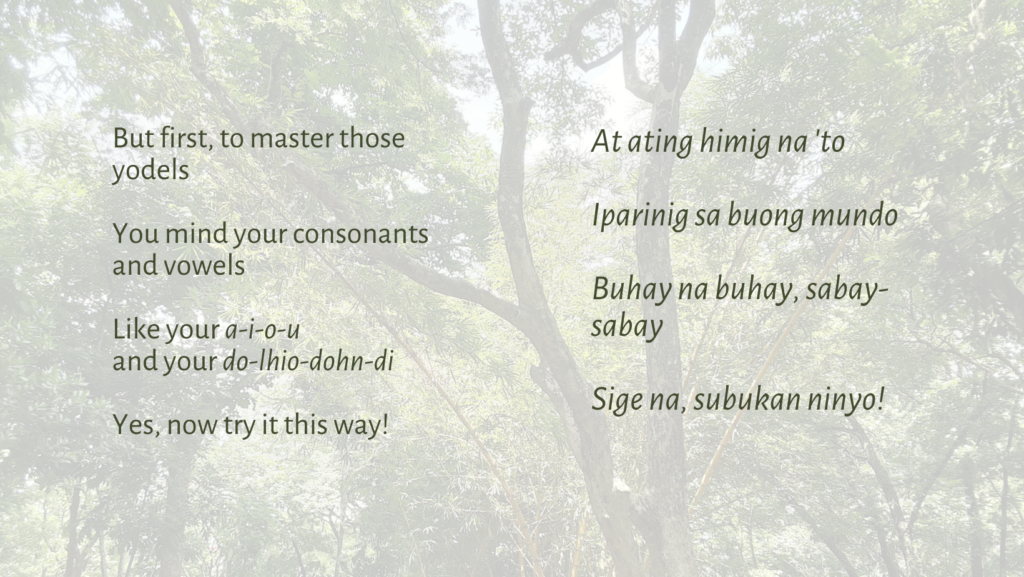

Unfortunately, I had not considered the problem of loose syllable structures in the lines of “Pangarap ay ating makakamit” and “Magyo-yodel ka rin.” This is more evident in the former since kamit ‘attain’ has the primary stress on the last syllable, but I could not help lengthen, and thus emphasize, the first one in my singing. As for the latter, I could have added na after ka, which would also have been more appropriate in an auditory sense. However, the English equivalent for na was absent in the first verse, which must be why it never crossed my mind.

While I did aim for semantic accuracy, I knew the retention of the general sentiment took precedence–especially since I was working with a song. I remember rewatching the different versions in other languages, in the attempt to understand the message of “Yodel Day” as a whole. I would then just re-package it in the words and constructions that Tagalog permitted. From “At ating himig na ‘to” until the last lines, this was the method I used, rather than direct translation. Thus, it seemed more apt to say that these were original, as mentioned in the video credits.

Actually, originality and artistic instinct was fairly emphasized in the whole translation experience. When I shared the initial complete set of lyrics with my family for some feedback, I was advised to avoid gasgas ‘hackneyed’ expressions. For instance, “buhay na buhay” was originally “hawak-kamay,” since I had wanted to be faithful to the content of the other versions.

Furthermore, when I presented the complete lyrics to Mr. Lim for approval, he asked if there was no translation that could be made for the phrase “World Yodel Day” itself. The combinations of words that immediately popped up in my head did not sound appealing at all, and I explained that I wanted to retain the concept associated with the phrase, since it was a proper noun–which he understood.

Lastly, for the title, I settled with “Araw ng Yodel” (“Day of Yodel”), rather than “Yodel na Araw” or “Araw na Yodel.” Either of the latter two seems more accurate for the phrase “Yodel Day,” wherein the Yodel modifies the Araw, but it made no semantic sense to me. Thankfully, Mr. Lim encouraged me to do what I thought best.

I thus realized that, in operating within the bounds of the target language and of art expressed in it, one can make room for semantic–but never sentimental–compromise.

#yodelingg: The backstage version

Furthermore, being involved in this event, I was able to apply linguistic study beyond musical performance–particularly, in published translation and subtitling. Mr. Lim had asked me to translate into Tagalog the titles and descriptions of several videos of the event, which may be seen on YouTube if the application’s language setting is set to Tagalog. I also provided Tagalog subtitles for the Chinese yodelers’ production.

Imagine my surprise, however, when he also challenged me to translate the description for “Araw ng Yodel,” along with its lyrics, into Japanese! Wanting to put my Plan C skills to the test, I accepted it happily, though I had a major setback with the last line, “Bawat puso’y mag-aalay.” The SOV structure of Japanese would not permit an implied, unstated object; and I tried searching for an intransitive form of ‘offer,’ but to no avail. Thankfully, I remembered that brackets existed! And, as was the case with Tagalog, I had my drafts proofread by a native speaker (who, interestingly, had also been one of the Japanese exchange students of the Department!).

Now, in translating prose, in comparison to lyrics, one would expect that there would be greater restrictions to creativity. However, I found that, in prioritizing the general sentiment over phrasal and sentential accuracy, it would not only be easier to understand the translation, for the reader; but also to write it, for the translator herself. To express myself freely in the target language, I would have to untangle my thoughts from the constraints of the source language text (mainly syntactic) that my brain had just absorbed. As with “Araw ng Yodel,” I just had to identify the entities involved in the text and how they related to each other, and rephrase it all in a way that captures the mood of the original. It was indeed mentally taxing, but well worth it.

From here on out: #Godwillingg

In the Filipino music scene, it seems that the only artist to have taken yodeling seriously was Fred Panopio. Additionally, I have not encountered any Filipina singer who openly identifies herself as a yodeler, so it would be very exciting if I were in fact the first.

Most of my yet unreleased originals do incorporate yodeling, with some of them having a more Western flavor, like that of Panopio. Thanks to this event, though, and the opportunity of national representation, I had been compelled to experiment on blending yodeling with traditional Philippine musical techniques, which–thank God–actually worked. This was done first with the classical kundiman vibe in “Yodel ng Tahanan,” and I intend to make more of such works. In addition, the voice break has generally been discouraged in the classical singing tradition (Wise, 2007), so it presents a tantalizing challenge.

This experimentation is also evident in “Araw ng Yodel,” of course; with the kulintang, dabakan, and tongatong in the mix. The project was thus not only a linguistic journey, but a cultural one, even if only as a personal listening experience. I am thus eager to further explore how such instruments can color my artistry as a yodeler in, from, and of the Philippines, whether for the international or local stage. This may even be an avenue to learn more about and support the communities that produced them, as well as their languages.

There are also opportunities beyond that of performance. A system of yodeling notation has never been developed, since the art is mainly learned by ear and improvisation–unlike classical music, which is learned by scores (Wise, 2007). It may then be possible to develop one using the IPA and traditional music theory, for pedagogical purposes. Thus, it may also prove fruitful to pursue linguistics and musicology, in academic tandem, as well.

For now, however, I’m content with celebrating the rarity and eccentricity of the yodel, as well as the blessings that have come along with it; and I am beyond grateful to have the responsibility of promoting it alongside elements of our traditional culture. My deepest thanks to God for allowing me to represent the nation in terms of this unique art, and that in my participation in its worldwide celebration–from performance to publication–I have been able to apply and further appreciate what I have learned as a student of linguistics.

[Julia’s short lecture on the science of yodeling can also be viewed here.]

References

Leuthold, H. (1981). Der Naturjodel in der Schweiz. Robert Fellmann-Liederverlag.

Mandal, D., Chandra, S., Lata, S., & Datta, A.K. (2011, August 27-31). Places and manner of articulation of Bangla consonants: An EPG based study [Conference presentation]. INTERSPEECH 2011, 12th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, Florence, Italy.

Melissa Xiaolan Warren. (2017). Yodeling is meant to exaggerate the “break” between registers. Julie had been classically trained for most of her life and [Comment on the video Maria von Trapp teaches Julie Andrews to Yodel]. YouTube.

O’Grady, W.D., & Archibald, J. (Eds.). (2015). Contemporary linguistic analysis: An Introduction. (8th ed.) Pearson.

Wey, Y., & Metzig, C. (2021). Machine learning classification of regional Swiss yodel styles based on their melodic attributes. Music & Science, 4, 1-12.

Wise, T. (2007). Yodel species: A typology of falsetto effects in popular music vocal styles. Radical Musicology, 7.

Published by Julia Martha Magno