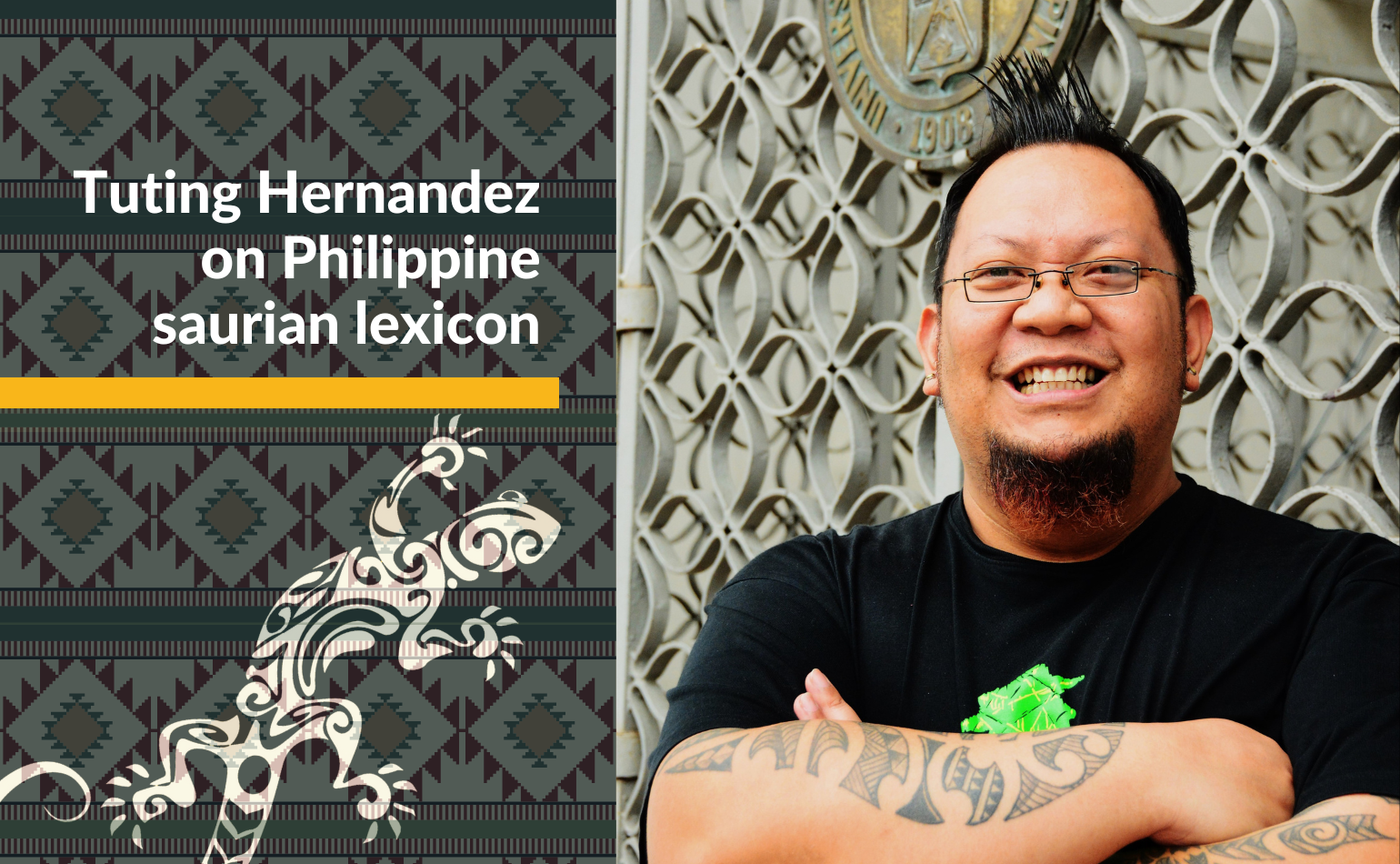

An exploratory essay written by Assoc. Prof. Jesus Federico Hernandez was included in Dr. Allan N. Derain’s (Ateneo de Manila University) latest book Pangontra, which was published by UP Press. The book that re-examines popular stories and re-introduces characters from folk literature in an attempt to (re-)present views different from long-established ones.

Hernandez’s essay, titled “Butiki: A Saurian Tribute,” looks into the words for lizard in various Philippine languages and identifies the etymological similarities and differences among the native terms. Initially shared to the public as a Facebook post, this preliminary analysis of lizard lexicon demonstrates the intricacies of studying word origins and the kinds of inquiries historical linguists usually formulate and strive to answer.

Hernandez observed that many of the elicited lexical items can be grouped into the following major forms: tuko, suksuk, tagaw, alutiit, talutu, tabili, and tiki. He provided brief explanations as to how these words came to be and presented reconstructions of their proto-forms (i.e, the putative forms of the words in an earlier ancestral language from which the current languages evolved). He mentioned for example that tuko likely originated from what speakers perceived to be the sound that geckos make.

Hernandez also pointed out the distribution of these terms to specific geographic locations (e.g. alutiit forms can be found in Ilokano-speaking areas of northern Luzon, while talutu forms are used in Visayas and Mindanao). He also mentioned observable changes, such as the semantic shift undergone by tabili ‘garden lizard’ in several Bikol and Visayan languages, in Bikol-Naga where it means ‘house lizard.’

Furthermore, Hernandez posed questions that prompt further investigation on what he identified as possible petrified affixes, cognate words, and resulting implications based on the relatedness of these forms in different languages. One of the questions he asks is whether the bu- in butiki actually an affix and if it is related to the bu- in buwaya and bubuli, which are different animals that nonetheless have similar physical forms. If so, it would make it similar to the more familiar petrified prefix (k)ali/alu, which occurs as the initial segment to certain animal names, such as, alimango, alimasag, alibangbang, alitaptap, and alupihan in Tagalog; alutiit and alibut in Ilokano; and alipa in Ibanag.

Hernandez emphasized that the practice of learning more about the knowledge systems as encoded in various languages and cultures across the country–particularly those that are still understudied and underrepresented–is crucial to identifying and re-evaluating previously-identified defining concepts of Philippine culture, which include the concepts of loob, hiya, and kapwa. He asserted that through this method, “we will [perhaps] be able to categorically and inclusively answer what defines us” and that “this will immensely contribute to the indigenization and decolonization of the social sciences.”

Pagbati, Sir Tuting!

Published by Patricia Anne Asuncion