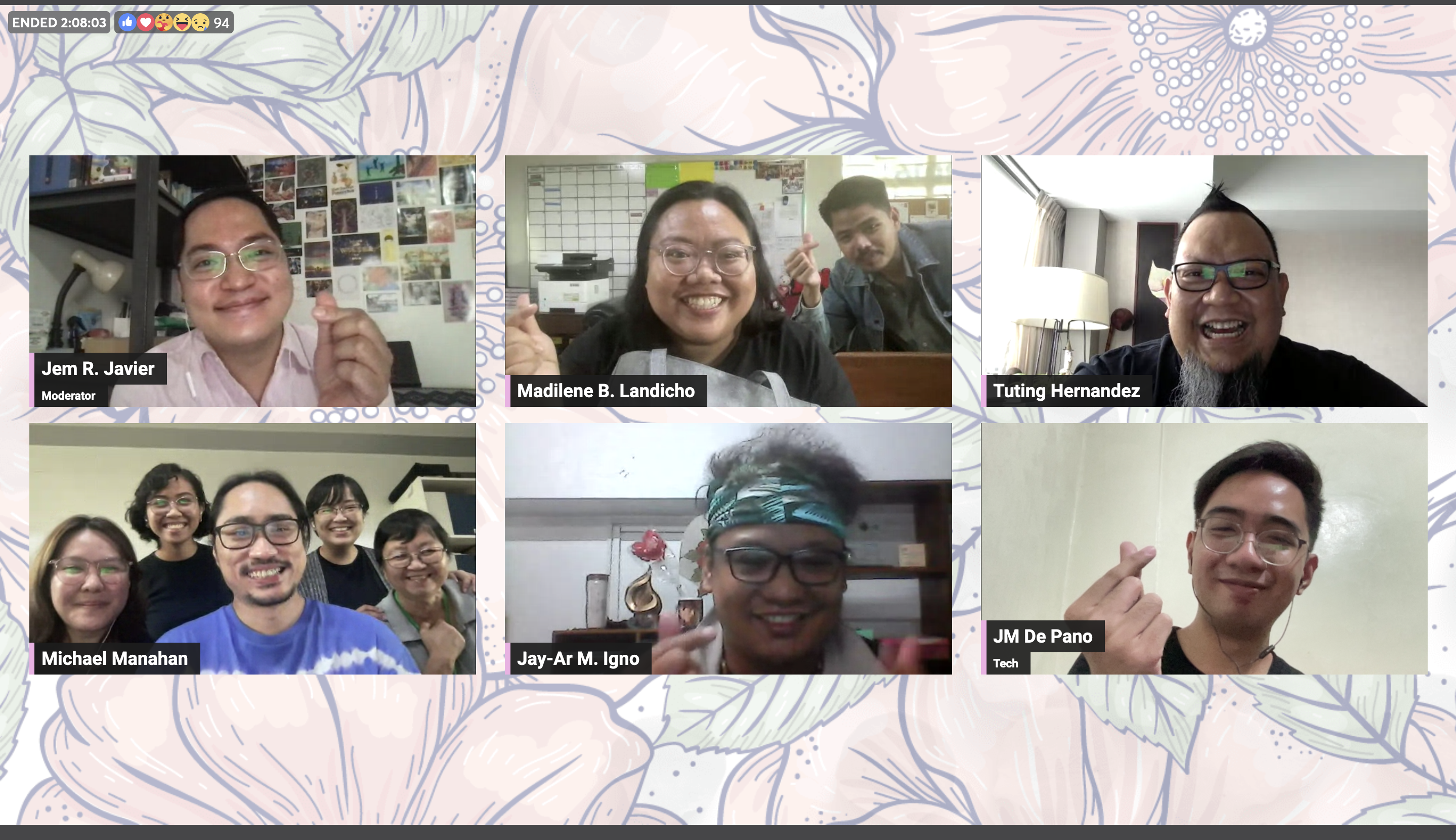

Lexicon Unpacked, which previously delved into the concepts of laya, alay, maláy, and sakít, focused on pag-ibig (‘love’) for its third installment. The webinar, held last February 14 and moderated by Asst. Prof. Jem R. Javier, featured studies that examine love as reflected in Tagalog and other Philippine languages, in a local tradition, and in songs.

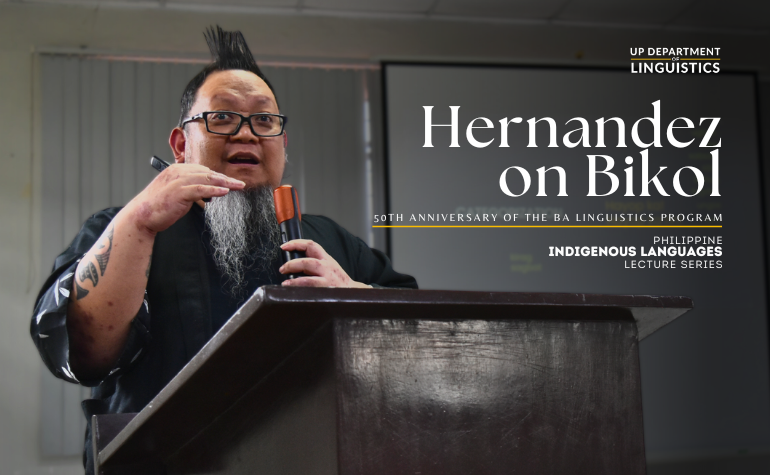

In the presentation titled “What’s love got to do with it? Dayakronikong pagsusuri ng mga salitang may kinalaman sa “love” sa wikang Tagalog,” Assoc. Prof. Jesus Federico C. Hernandez traced the provenance of the words mahal and ibig, and listed several remarkable cognates to reveal what these words for love actually entail.

After sharing that the dictionary definitions of mahal center on ‘being expensive’ and ‘love’ (Noceda & San Lucar, 1860; Almario, Ebreo & Yglopaz, 2013; Panganiban, 1972), Hernandez mentioned the possibility that the latter is a semantic expansion of the former, and that this can be supported by the idea that both meanings relate to ‘valuation’ and ‘estimation of worth.’ Related forms present in Bikol and Cebuano possess the sense of being expensive, which they share with other Western Malayo-Polynesian (WMP) languages. It was also hypothesized that mahal came from India, moved southwards, and was introduced to Tagalog-speaking areas through contact with Malay speakers. Ultimately, mahal is derived from mahā ‘great, big, high’ (with PIE root *meg- ‘great’) and arghá ‘price’ (where Tagalog halaga ‘price, worth’ is derived from).

Meanwhile, Tagalog ibig comes from PMP *ibeR which means ‘saliva in the mouth; drool; watering at the mouth (because of strong desire); desire, crave, lust for, covet.’ Apart from related words that pertain to ‘desire’ and ‘attraction’ (e.g., those found in Pangasinan, Hanunóo, Aklanon, Cebuano, and Hiligaynon), ibig has some interesting cognates: Kapampangan ibug ‘have a taste for’; Tiruray ʔibeg ‘appetite; saliva’; Tboli iwol ‘saliva; to drool over, to want something very much’; and Rinconada ibug/ibég ‘envy.’ Outside the Philippines, in languages such as Ngaju Dayak, Malagasy, Mongondow, Palauan, and Kayan, it refers to ‘saliva in the mouth.’

Hernandez tied his discussion by posing the following questions: If love is really a strong emotion, why does it seem that it is not reflected in Tagalog and, more generally, the Philippine lexicon? (Words for love do not have a wide distribution in Austronesian languages, have no enduring form, and take on different forms in related languages.) If it is a core concept, why is it evident only as a secondary development in terms of word meanings?

For the second part of the webinar, Asst. Prof. Madilene B. Landicho from the UPD Department of Anthropology shared her study of gawaan ng magaling, a practice observed by two parties regarding (pre-)marriage arrangements and negotiations. Landicho’s discussion was based on personal observation and information gathered from informal interviews with elder community members of several towns in Batangas, primarily those surrounding the Taal Lake and Taal Volcano.

Gawaan ng magaling, also called bulungan (lit. ‘whispering’) and pamulungan (lit. ‘gathering’), is somehow similar to the practice of pamamanhikan, where the family of a man meets the parents of a woman to seek approval regarding marriage. It is an important local tradition in Batangas where both parties agree on the details of the wedding and discuss other matters concerning the union of a man and a woman.

Landicho explained that before gawaan ng magaling proceeds, an informal process takes place: the couple informs their own parents; the male’s party reaches out to the female’s parents; a date is to be set; and a tagatala ‘negotiator, moderator’ for each party is assigned. And as a community activity, gawaan ng magaling requires the participation not only of the nuclear family, but also of important and closest relatives, including the oldest members of each clan. It also follows certain customs such as the kind of food to be served and the objects that need to be brought inside the house (i.e., tibunglos ‘lamp’ and water in a container, the former believed to bring light to the family and the latter symbolizing calmness and steadiness in the couple’s relationship).

Particular details decided upon on this occasion include the wedding date, the place where it will be held, the type of wedding (i.e., church or civil wedding), food, attire, and other setups. It is also crucial to identify who the ninong (‘godfather’) and ninang (‘godmother’) will be for they are expected to give a substantial amount of sabog ‘money gift’ to the newlyweds.

Asst. Prof. Landicho concluded her presentation by speculating what mamagaling/mapagaling might mean based on how it is usually used in contextual expressions: mapabuti [ang hinaharap] (‘have a good future’), mapaganda [ang kapalaran] (‘have good luck’), swertehin [sa buhay] (‘be fortunate in life’).

Finally, Asst. Prof. Jay-Ar M. Igno talked about his preliminary study regarding the concept of mahal in Original Pilipino Music (OPM) using an ethnosemantic approach. His work aims to explore the role of songs in assessing one’s emotions and their function as a form of self-expression.

For his corpus, Igno compiled songs from five distinct decades containing the word mahal in their titles. He presented select song lyrics and identified which ones feature an agent, patient, and/or goal. Part of his attempt to formulate ethnosemantic interpretations is the identification of thematic roles, i.e. who are involved in the portrayed expressions or metaphors in love songs. By examining feelings, intentions, and relations in songs, the study can contribute to further understanding of certain cultures, traditions, and social relations that operate in Philippine society.

Questions raised during the open forum focused on the semantic shifts undergone by ibig, the hierarchy or intensity of synonymous love words, and the economic and performative aspects of gawaan ng magaling. Overall, the presentations offered alternative ways of defining and performing love, and consequently challenged some traditional notions through linguistic and anthropological evidence.

The recording of Lexicon Unpacked: Pag-ibig can be viewed on the Department’s YouTube channel.

Published by Patricia Anne Asuncion