The Department organized a two-day lecture-workshop on Japanese language education in the Philippines last June 23 to 24 at Palma Hall as part of its Talks on Asian Languages series. The in-person event was co-organized by the Department’s Japanese Language Cluster and The Kamenori Foundation, in cooperation with The Japan Foundation, Manila.

This gathering of institutions, scholars, educators, and learners served as a space for dialogue regarding teaching principles and strategies that would hopefully develop innovations in the expanding Japanese language education (JLE) in the country. More specifically, this event aimed to share local and international trends in JLE; conduct a workshop on classroom activities and assessments; and discuss the feasibility of establishing a network of researchers and educators of Japanese language in the Philippines.

JLE situation in the Philippines

Department Chair Kristina Gallego formally opened the event by welcoming and thanking the guests. Her brief message highlighted the essence of strengthening support systems among educators and motivating researchers who embark on different academic explorations.

On the first day of the lecture-workshop, seven resource persons shared their observations and insights on the situation of JLE in the country. Mr. Takeshi Matsumoto presented a broad overview based on various statistics compiled by The Japan Foundation, Manila. He focused on trends in the number of institutions, teachers, and learners grouped according to the kinds of JLE in the Philippines. Aside from those incorporated in primary, secondary, and tertiary levels, there are also JLE classes that cater to nurses and caregivers, skilled workers, Japanese descendants, and others who are interested in Japanese culture. Matsumoto ended by interpreting what these trends imply and locating the Philippines in the global context of JLE.

Next, Ms. Michelle Bangoy (Jose Abad Santos High School) provided information regarding the Special Program in Foreign Languages (SPFL), which is one of the special curricular programs implemented by the Department of Education (DepEd) at the secondary level. She also discussed how this program is being carried out in their high school, highlighting the challenges they encounter and identifying possible solutions.

Succeeding presentations were updates regarding JLE in Luzon, Visayas, Mindanao, and Metro Manila. Ms. Rowena Okabe (University of the Philippines Baguio) gave a preview of how Japanese language is taught as an elective in UP Baguio and also mentioned some details about JLE in other northern universities like the University of the Cordilleras and St. Louis University.

Retired professor Dr. Maria Rosario Piquero Ballescas (University of the Philippines Cebu) offered a summary of statistical data on JLE teacher and student populations in Visayas, and described developments in the establishment of both school-based (i.e. colleges and universities) and non-school-based institutions offering Japanese language classes. She also elaborated on curricular details and activities before ending with personal accounts from some students who took Japanese language classes in UP Cebu.

Aside from pointing out the parallelisms in the narratives of JLE in Luzon and Visayas, Dr. Jose Marie Ocdenaria (Ateneo de Davao University) underscored the importance of offering Japanese language courses in Mindanao, as well as the related motivations of learners–both students and adult professionals–in enrolling in such classes.

Meanwhile, Assistant Professor Ria P. Rafael (University of the Philippines Diliman) introduced the Department’s Japanese language program, the requirements for linguistics majors specializing in Japanese language, and the profile of instructors handling Japanese classes.

Lastly, Mr. Renan K. Gonzales (TESDA National Language Skills Center) briefly described TESDA’s Japanese language and culture program, and how it facilitates its Training for Work Scholarship Program (TWSP).

After the resource speakers’ presentations, Dr. Yasu-hiko Tohsaku (University of California San Diego), shared his insights and commented on the current situation of JLE in the Philippines. Prof. Tohsaku first explained how foreign language education fares in the United States and how the pandemic affected its operation in recent years. He then drew comparisons between the state of JLE in the US and the Philippines, and he expressed his hope for the continued enhancement of language education in the latter.

Current research in JLE in the Philippines

The second part of the program on the first day spotlighted research projects that investigate various aspects of JLE. Ms. Francesca Ventura (JFM-Marugoto Team) expounded on her comparative study of Kanji learning beliefs and strategy usage among Filipino learners and teachers. At the heart of this research is an adapted Kanji learning model, which takes into account factors such as a student’s personal characteristics, learning environment, sociocultural background, and learning outcomes.

Probing the idea of “studying smart” during asynchronous sessions, Ms. Bernadette S. Hieida (De La Salle University) discussed her findings derived from surveys and interviews with teachers and students. Her study sought to answer the following questions: (1) How did Filipino teachers improve the way they conducted Japanese classes during asynchronous sessions; (2) What are the feedback from the students; and 3) How did the teachers’ initiatives affected the students’ learning journey.

Dr. Jose Marie Ocdenaria’s (Ateneo de Davao University) case study touched on the challenges frequently faced by learners. Common limitations identified include problems with characters, vocabulary, and grammar. He concluded by emphasizing the need for consistency, guidance, and time allotment in this endeavor.

Finally, Ms. Yuko Fujimitsu (The Japan Foundation, Manila) imparted the idea of teachers being practical researchers. She also explained the importance of creating a community of educators where experiences, strengths, and even weaknesses can be communicated and evaluated as a team.

During the open forum, several Japanese language teachers shared their comments and realizations regarding the presentations.

The first day of the event closed with a proposal for nurturing a community of researchers where, in the words of Assistant Professor Farah C. Cunanan, stakeholders “can talk about research ideas, problems, interests [which can later be] adopted to classes.” She pointed out that “to envision what the future of Japanese language education in the Philippines would be like, [educators] have to come together.”

Challenges and Prospects

The second day began with the welcome remarks delivered by Ben Suzuki, director of the Japan Foundation, Manila. He was followed by Ms. Hiroko Nishida, Secretary General of The Kamenori Foundation, who introduced Dr. Tohsaku and the theme of of his lecture, titled “Educating Global Citizens in the 21st Century: Challenges, Prospects, and Strategies for Foreign Language Education”

Dr. Tohsaku started his lecture by describing the ideal kind of education as pragmatic, that is, one that nurtures efficient and productive individuals by imparting practical knowledge and skills. He remarked that this sort of education is necessary in order to survive in the 21st century, a period characterized as volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous. He also stressed that the keyword of today’s world is “connect,” which is embodied by relationships shared among people, societies, cultures, and political systems. Thus, as members of the global community, we must acknowledge that our actions and choices have an impact on others. It is this connection that is imperative in addressing issues related to poverty, human rights, and peace maintenance.

He proceeded by explaining that an important connecting instrument available to us is language since it serves “as a powerful tool for communication between individuals and the community.” Language can further be utilized through what he terms the Social Networking Approach (SNA), which prompts individuals to know about others in order to know themselves better. He also said that the ultimate goal of language education must be human growth leading to global citizenship and improvement of life.

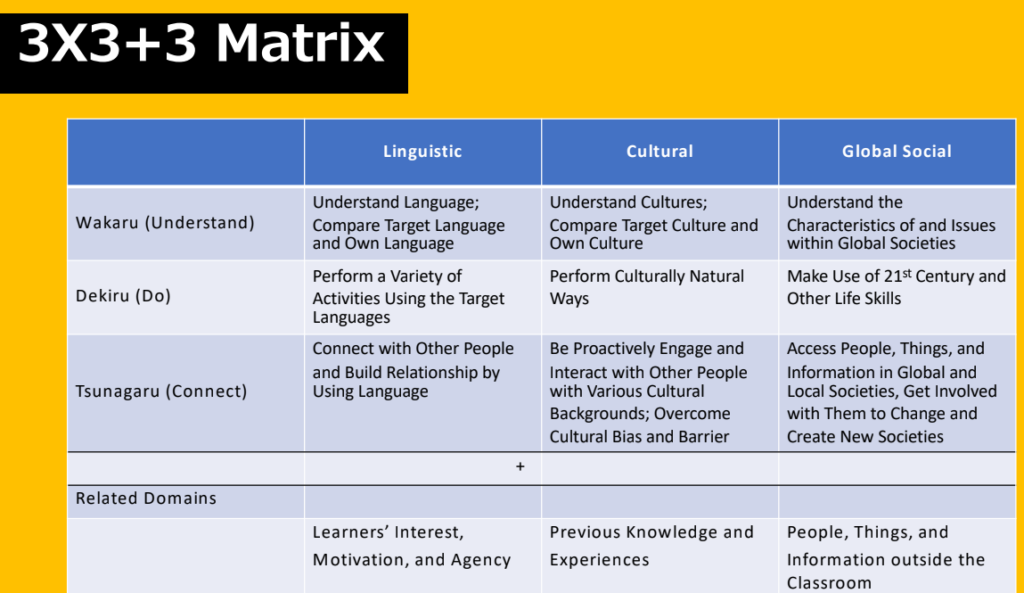

He went on to discuss SNA’s learning goals by presenting a “3×3+3” matrix. This matrix plots the relationship among three content areas (i.e., linguistic, cultural, global-social), three skill areas (i.e., wakaru ‘understand,’ dekiru ‘do,’ tsunagaru ‘connect’), and three related domains (i.e., learner’s interest, motivation, and agency; previous knowledge and experiences; people, things, and information outside the classroom). He observed that since current educational paradigms mostly focus on linguistic and cultural understanding and doing, it is time to work towards global-social connection. And while there is no single, optimal teaching method, educators have the role and responsibility to act as instructional designers.

The rest of his lecture covered examples of activities (e.g., creating virtual school trips and podcast episodes) in which these learning goals can be achieved. In comparing the SNA with the traditional approach to learning and language teaching, Dr. Tohsaku highlighted the advantages of employing strategies and processes that highly engage and motivate students.

Dr. Maria Sheila Zamar (University of Montana – Missoula), designated as the reactor to Prof. Tohsaku’s lecture, reiterated two important points. First, the goal of language education is not simply to make students learn grammar and pass certain tests—it must instill in learners the idea of being effective global citizens through language learning. Second, humans are life-long learners. We must thus understand that learning should continue outside the classroom, beyond class hours.

Maximizing Learning in the Language Classroom: Effective Strategies for Instructional Design

The second half of day two was devoted to a workshop on strategies for instructional design. Dr. Tohsaku reminded the participants that teachers are expected to “design and create optimal environments and conditions for maximizing learning.” Given that learning transpires in the students’ brains, educators should help in generating opportunities for students to think on their own. Learning can also be maximized through one’s readiness to engage with learning goals, learning contents, other learners, teachers, and the outside world.

After giving instructions regarding the workshop’s activity, Dr. Tohsaku shared a quote from the educator A.J. Juliani: “Our job as teachers is not to prepare kids for something. Our job is to help kids learn to prepare themselves for anything.”

Several groups then volunteered to present their work and were able to receive feedback from the audience. Some activities featured basic Japanese language learning tasks for caregivers, a food expo for high school students learning Japanese, a lesson plan for learning Korean, and a buddy system for learning Filipino.

Congratulations to the Japanese Language Cluster for this successful event! We look forward to future gatherings of Japanese language scholars and educators in the near future.

Published by Patricia Anne Asuncion