The Department of Linguistics, in celebration of the UP Diliman Arts and Culture Festival (UPDACF) 2022, presented the first installment of Lexicon Unpacked, focusing on the terms alay, maláy, and laya. The webinar, conducted on 17 March 2022, also served as the first event in anticipation of the Department’s centennial year.

The lexicon of a language, the project brief states, is rich in information formed and molded by history and culture and can be examined using different linguistic methodologies. One can therefore uncover not just the present use and denotation of a word, but also the history, context, and value placed upon the concept that it refers to. In Philippine history, the GomBurZa martyrdom in 1872 is considered to be a historical turning point that solidified the Filipino consciousness of a nation that should be free from colonizers. And so, in keeping with the theme of UPDACF 2022, “kaMALAYAn: Pamana ng GomBurZa @ 150”, the words alay, maláy, and laya were dissected using different linguistic approaches, namely: diachronic linguistics, metaphor studies, natural semantic metalanguage (NSM), discourse analysis, ethnolinguistics, and frame semantics.

Unpacking laya

Instr. Michael Manahan examined laya using Natural Semantic Metalanguage (NSM). This approach employs reductive paraphrasing in which the meaning of words and expressions is restated using semantic primes to produce explications. It is a part of the cognitive linguistics movement and was develop as a tool for semantic analysis (what does this word mean) and cultural analysis (what is the meaning assigned by the speaker to this expression).

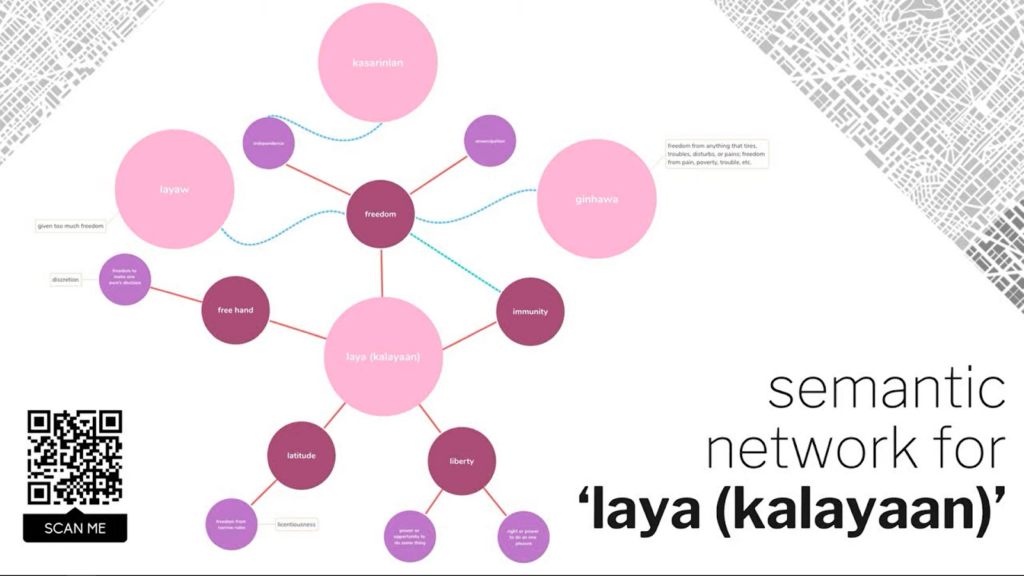

The corpus, comprised of words collected from dictionaries spanning a 50-year period (1971-2021) and the 1987 Constitution, yielded 34 expressions (and derivatives) related to laya. Manahan plotted these expressions to create semantic network which shows how these words and the meanings that they embody relate to each other.

Laya is broken down into its component features, shown in their NSM explications:

- Liberty, free will, latitude

- “If I want to do something I can do it”

- “If I don’t want to do something I don’t have to do it”

- Doing something within bounds

- Immunity

- “I don’t have to do something; many people have to do this”

- With related concepts of exemption, or exclusive exercise where only a subset experience this

- Free hand or discretion

- “I can do something; no one else can say to me you can’t do it”

Those above have an emergent theme of “doing something” which can be “something you want to do”, “something you don’t want to do”, “something other people have to do”, and “something that can potentially be done”.

- Freedom, emancipation, independence

- “If i want to do something I can do it now; for a long time, I can’t do what I want; this is good for me”

This entails a change of state from being restricted to being less restricted or the negation of the limitations imposed at an earlier time.

- Liberty, right or power to do as one pleases, power or opportunity to do something

- A value judgment that “this is good for X”

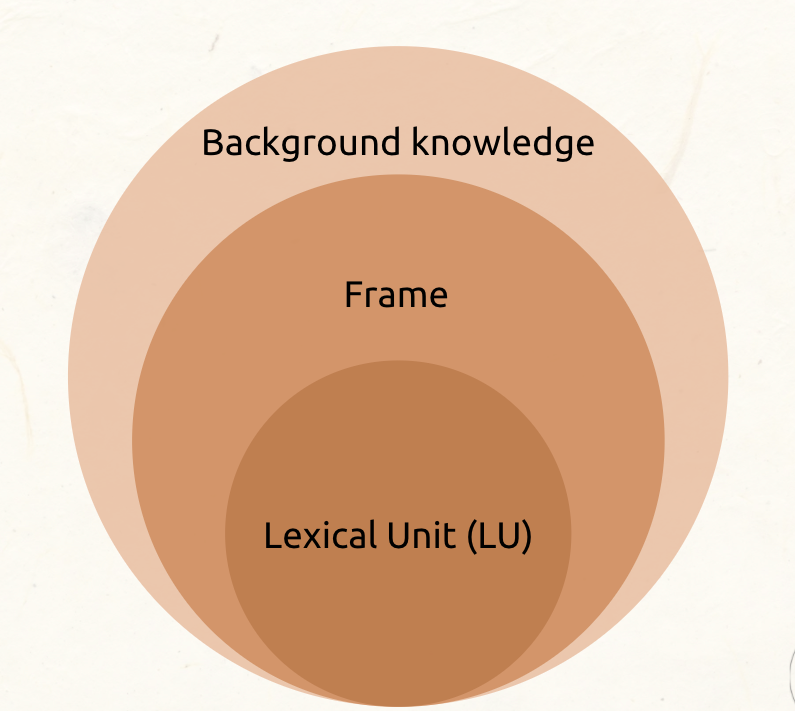

Meanwhile, Asst. Prof. Elsie Marie Or used Frame Semantics Analysis to look into laya. The frames approach to analyzing meaning looks at how “linguistic forms evoke or activate frame knowledge and how the frames thus activated can be integrated into an understanding of the passages that contain these forms” (Fillmore & Baker, 2009). A word evokes a frame which is based on background knowledge; thus, this approach relates the speaker’s linguistic knowledge to their encyclopedic knowledge.

As Frame Semantics posits that elements relevant to the frame evoked by a lexeme map onto linguistic structures, Or identified the combinatorial patterns that the word laya has. She noted that word can take actor and patient focus, but that it cannot combine with locative, benefaciary, and instrument focus affixes, which indicates that the core or main foregroundable elements of the frame that laya evokes are the Agent (ang nagpapalaya) and the Theme (ang pinapalaya), with an additional core frame element which indicates the location of confinement from which the theme might “escape” from, given the high frequency of the word’s collocation with mula ‘from’ as observed in the Leipzig Tagalog Corpus.

Taking a look at the constraints in the word’s aspectual forms, Or also pointed out how Tagalog conceptualizes laya as a state which an entity either achieves or does not. It does not evoke a procedural action with a possible liminal state. Either one is free, or one is not. However, it is curious that the word can also combine with quantifiers that indicate varying degrees of freedom (e.g., kaunting kalayaan, mas malaya, pinakamalaya).

Towards the end of her discussion, Or also compared laya to other words that might be considered as its close synonyms, namely takas and wala (i.e. kawala), to show how frame semantics can elucidate the differences.

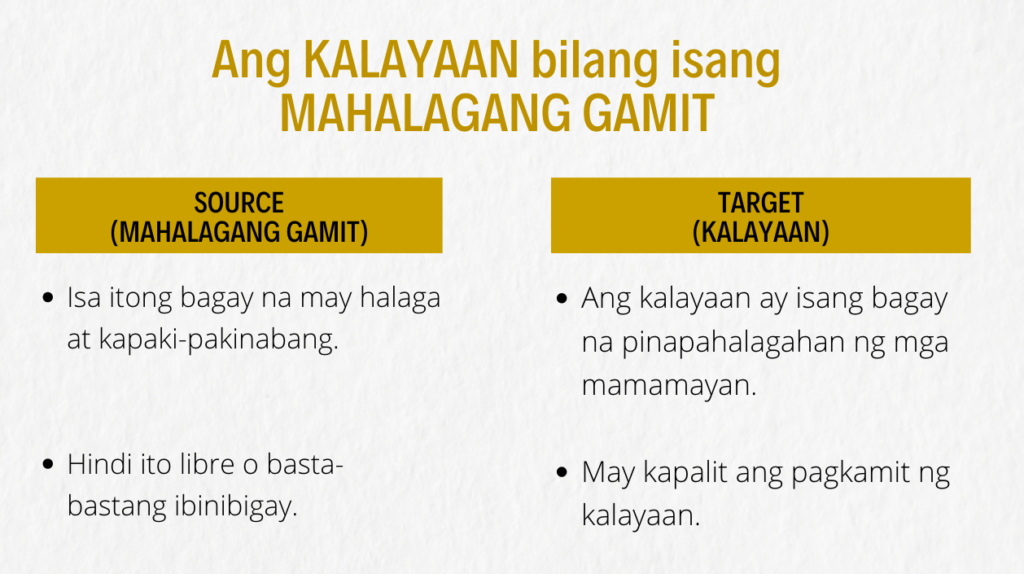

Asst. Prof. Francisco Rosario, Jr. used the lens of Conceptual Metaphor Theory to approach the meaning of laya. Conceptualized by Lakoff and Johnson (1980), who suggested that metaphors are not only used artistically, but it actually permeates the language that we use in our everyday life. It aims to describe how the mind appropriates or ‘transfers’ concepts from the concrete/physical Source Domain to the abstract Target Domain.

Rosario drew from a corpus comprised of literary texts, such as Kahapon, Ngayon, at Bukas by Aurelio Tolentino, the transcriptions of State of the Nation Addresses (SONA) of former President Benigno Aquino III, as well as posts on social media, to identify the metaphoric conceptualization of laya. He made the following observations:

- Ang kalayaan ay isang bagay na pinapahalagahan ng mga mamamayan. (‘valued by the community’)

- May kapalit ang pagkamit ng kalayaan. (‘there must be something in exchange’)

- Para makamit ang kalayaan, kailangan itong paghirapan. (‘should be labored to be attained’)

- Maraming magagawa kapag malaya. (‘a lot of things may be done in this state’)

- Maaaring mawala ang kalayaan. (‘may be lost or taken away’)

From these, kalayaan is seen as a thing (“mahalagang bagay”) which is important and useful, something that takes effort, and can be lost or taken away.

Unpacking alay

Instr. Noah Cruz explicated alay using Componential Analysis, a method developed by Eugene Nida in 1950, where the meaning of a word is seen as a unit composed of various semantic components. Words have meaning “only in terms of semantic contrasts with other words which share certain features with them but contrast with them in respect to other features”. Common components group meanings while diagnostic components differentiate them.

Using corpus from the dictionaries of José Villa Panganiban (1972) and Fr. Leo English (1986), alay emerged as closely related to kaloob, handog, and regalo. Broken down into its features, this is how alay compares to the other concepts:

Bigay is the common component while the diagnostic components are kusa / bukal sa kalooban, pagsasakripisyo, and sagradong layunin. Based on this, alay can be defined as “bukal o hindi bukal na pagbibigay, nang may sinasakripisyo para sa isang sagradong layunin” (‘giving willingly or unwillingly, sacrificing for a sacred or a higher cause’).

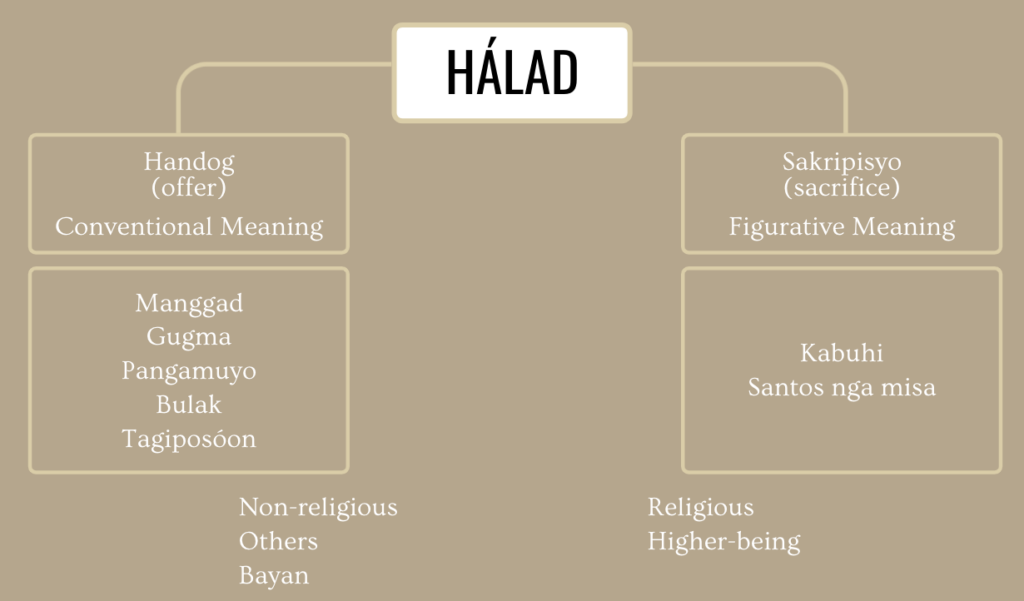

Assoc. Prof. Mary Ann Bacolod used ethnolexicography to explain hálad, the equivalent of alay in Hiligaynon. The approach inspects the dictionary representation, underlying representation, and ethnographic semantics that, according to B. N. Colby (1966) studies the “aspects of meaning in a language that are culturally revealing”. It also follows the “Semantic Rules” of Jerrold Katz and Jerry Fodor and “Conventional and Figurative Meaning” by Charles Fillmore. Corpus was collected from Hiligaynon dictionaries and literature.

Ten senses were found for hálad:

- offering, sacrifice, immolation

- gift, donation, present

- dedication, oblation

- grant, bestow

Conventional meaning for the word involves ‘offering, handog, gift, present, donation’, while figurative meaning involves ‘sacrifice, oblation, grant, bestow, dedication, immolation’. In Alonso de Mentrida’s (1841) dictionary, hálad is the domain term for ‘holocausto, oblacion, ofrendar, sacrificio, votar’.

In general, hálad can be categorized into two: handog/offering and sakripisyo/sacrifice. What can be offered are riches (manggad), love (gugma), prayer (pagamuyo), flower (bulak), and heart (tagiposoon). For sacrifice, life (kabuhi) is offered or the mass (santos nga misa).

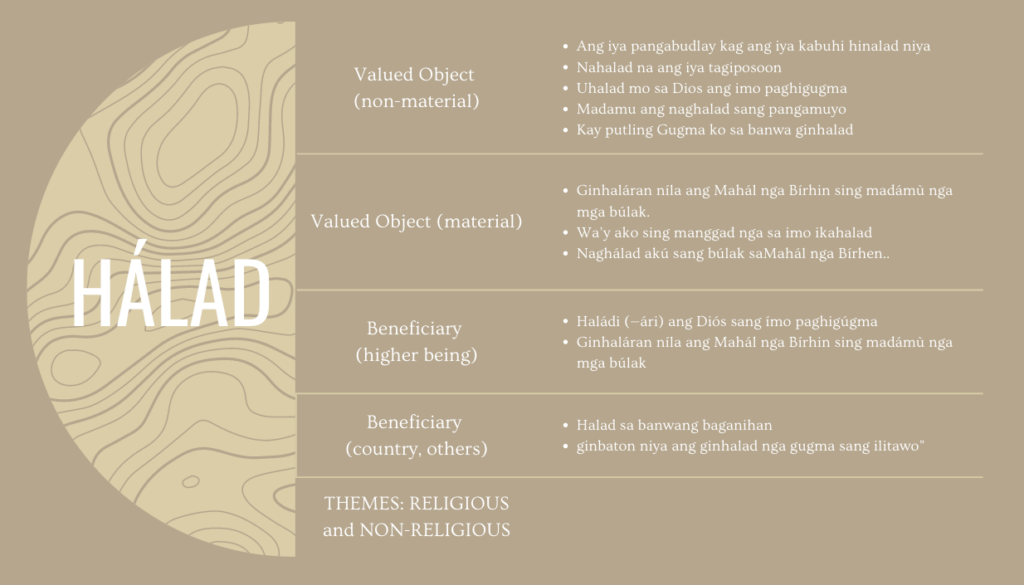

In summary, for the componential markers, it is grammatically marked by object focus and benefactive focus affixes and can be formed into nouns or verbs. Semantically, hálad can be religious or non-religious and there is a transfer of possession which can be ‘give’, ‘contribute’, or ‘provide’. For distinguishers, it distinguishes whether the entity for whom the offering is made is a higher being, the self, or others, and whether the object is material or non-material. In lexicographic representation, ‘offer’ is the conventional meaning and ‘sacrifice’ is the metaphorical meaning. This preliminary analysis categorizes hálad into the following:

Asst. Prof. Ria Rafael also looked into alay, this time through the lens of Discourse Analysis. This approach studies language in use or in context, language above sentence, and practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak, according to Michel Foucault (1971).

The corpus is collected from songs: offertory songs (alay to sacred beings), folk/protest songs (alay to country, which can be abstract/intangible), and love songs (alay to non-abstract benefactee).

From discourse, alay is an act (gumawa) which can be hierarchical—there is someone below offering to someone above (but sometimes it is vague). It is a thing (bagay) where value is assigned to the object being offered. It is given to the receiver (tumanggap) who is someone sacred or held in high esteem.

Unpacking maláy

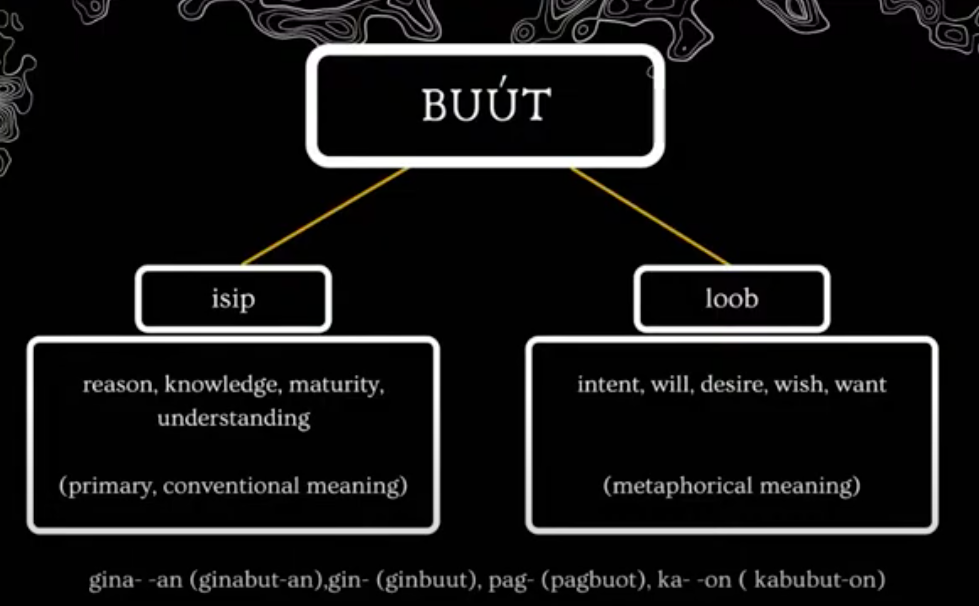

Assoc. Prof. Bacolod once again used ethnolexicography to explicate buút, the equivalent of malay in Hiligaynon.

The dictionary corpus revealed the following senses:

- Reason (conventional): razon, maturity

- Mind (conventional): understanding, intelligence, entendimiento, isipan

- Will (metaphorical): intention, desire, wish

From the sample phrases collected, the concept of loob also emerged. Buút is then categorized into three: isip, loob, and gusto (will, intent). From all the data, the following meanings were found:

- Cognition (knowing, understanding, thinking)

- Judgment (reason, maturity)

- Volition (will, want, desire)

- Purpose (intention)

In general, the concept of buút can be divided into two: isip as conventional meaning and loob as figurative meaning.

In summary, for the componential markers, it is grammatically marked by/for actor focus affixes, nominal marker, modal verb, existential, noun, and verb. Semantically, buút can mean ‘cognition, judgement, volition, purpose, and an ethical concept’. In lexicographic representation, ‘reason’ and ‘mind’ are conventional meanings and ‘will’ is the metaphorical meaning.

Lastly, Assoc. Prof. Jesus Federico Hernandez looked at malay through the perspective of diachronic linguistics and structural relations. Words do not occur in isolation; they have syntagmatic and paradigmatic relationships with other words. They also form experiences, conceptual domains, and are products of history. Thirty (30) dictionaries in 25 languages were searched for cognates of málay and maláy. Cognates surfaced only in the following languages aside from Tagalog, namely:

- Kapampangan malay ‘sense, manner, feel, perceive’, mále ‘consciousness’ (monophthongization)

- Bikol málay mo ‘who knows’ (phrasal)

- Romblomanon málay ‘(in anong málay)’ (phrasal, idiom)

- Cebuano málay walay ‘innocently unaware’ (phrasal)

It is noticeable how in the second to the fourth items above, the entries are phrasal, which leads to the question if they are products of borrowing. Three scenarios are postulated from this:

- The proto-Philippine form is lost in all other Philippine languages (PL) except in Tagalog, Kapampangan and survives in other Greater Central Philippine languages but only in fixed expressions;

- Málay is of Tagalog origin, borrowed into other PLs, e.g., Kapampangan phrase milako a male-tau ‘fainted’; and

- It is of non-Philippine origins, borrowed into TGL and consequently into other PLs as a phrasal unit.

The scenarios are currently inconclusive, given data in other dictionaries, e.g., in Tboli with an entry for málay ‘(of people) mature’. This brings up the question whether it is a cognate of the Tagalog málay or the similarity is by chance. It can be argued that they belong to the same semantic domain as we sometimes refer to children as wala pang malay o muwang.

It is interesting to note how there are only a few languages with málay/maláy cognates. Assoc. Prof. Hernandez then asked if it means that there is no sense of malay in the other languages? Looking into the domain of málay/maláy, it includes alam, bait, damdam, diwa, loob, muwang, ulirat, unawa. It is possible that the concept of malay is more prominent in the other words, e.g., buút in Hiligaynon, Bikol, with Tagalog bait as a possible cognate. From this research, it can be seen how genetic relations surface not just from the origins and evolutions of words, but also in relation to other words.

Open Forum

A lively discussion with the participants followed the presentations.

On the concept of laya, a webinar participant forwarded the idea that it is the default state but in the context of the Philippines, it is not. Asst. Prof. Rosario answered that in the Philippine contextualization of laya, it appears that it is something that requires effort (pinaghihirapan). It is interesting to look into how countries with no experience of colonization define freedom. For Asst. Prof. Or, it is difficult to say that being free is the default state based on its frame. But there is agency in it, a will to get or give freedom, and the ability to reach or bestow this state.

For alay, the question is on the difference of offering life as a volitional act (e.g., in war) and other people offering another person’s life (e.g., to appease an impending volcanic eruption). Asst. Prof. Rafael and Assoc. Prof. Bacolod agreed that the second context is not voluntary (kusang-loob) but is considered a sacrifice.

For maláy, as used in walang malay, an audience asked if it is used universally as physiologically fainting. Assoc. Prof. Hernandez noted that in the languages where cognates were found, it does have the sense of fainting but if the whole phrase is borrowed, the meaning does not come only from the word but the whole phrase/idiom. In Hiligaynon, Assoc. Prof. Bacolod said that it is not used in the physiological sense.

Some of the questions asked about data elicitation and methodological challenges. Instr. Manahan, Asst. Prof. Or, Instr. Cruz, and Asst. Prof. Rafael said that different approaches require a defined corpus, which can be a digital one like the Tagalog Leipzig Corpora Collection, dictionary sweeps, sample sentences in dictionaries and social/digital media, songs, etc. It is also important to note when the source was written as there might be differences in meaning depending on the time period.

Other questions were about the relation of words as used in politics and propaganda and how they limit our consciousness. Asst. Prof. Rafael answered that in discourse, when a word is used, it can be boxed into that meaning until it becomes the default for that certain discourse. There are also distinctive features and styles that are used to influence the audience. Assoc. Prof. Hernandez further reiterated how words are powerful, e.g., a look at social media would reveal how language is manipulated to achieve an agenda.

This webinar unpacked the usage of the words alay, maláy, and laya and unveiled meanings in the context of the collective Filipino experience, culture, and history. Subsequent installments of this activity will aim to uncover more words and reveal what they mean to Filipinos.

Moderator Asst. Prof. Jem Javier concluded the webinar by thanking the UP Diliman Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts who made the event happen. The first installment of Lexicon Unpacked was dedicated to Retired Linguistics Professor Consuelo Paz, who was celebrating her birthday on the day of the event.

The recording of the Lexicon Unpacked: Kamalayan webinar series can be viewed on our YouTube channel.

Published by Divine Angeli P. Endriga