What is the meaning of the word Lumad? What politico-historical events gave rise to Lumad collective identity? These questions and more were interrogated as UP College of Social Sciences and Philosophy (CSSP) alumnus and Mindanao State University Iligan Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT) associate professor Arnold Alamon delivered the 3rd Consuelo J. Paz Lecture at the 2nd floor lobby of University of the Philipines Diliman’s (UPD) Palma Hall on March 17, 2023. The lecture was the culminating event in a weeklong celebration of the life and works of Dr. Consuelo J. Paz, the “Grand Dame of Philippine Linguistics”. It was also delivered as part of the UPD Arts and Culture Fest 2023 with the theme “KALOOB mula at tungo sa Bayan: Artista-Iskolar-Manlilikha.”

Dr. Consuelo J. Paz, after whom the biennial lecture series is named, served as Chair of the UP Department of Linguistics twice and as Dean of the CSSP from 1992-1998. The highlights of her deanship include the founding of the Center for International Studies (CIS) and the establishment of the Inisyatibo sa Pag-Aaral ng mga Etnolinggwistikong Grupo (IPEG), later the Programa sa Pag-Aaral ng Etnolinggwistikong Grupo (PPEG). As a researcher, she published pioneering works in historical and comparative linguistics, sociolinguistics, and ethnolinguistics, while promoting ethnographic tools like fieldwork and participant observation. Dr. Paz was also among the key figures in the formation and development of Filipino as the national language.

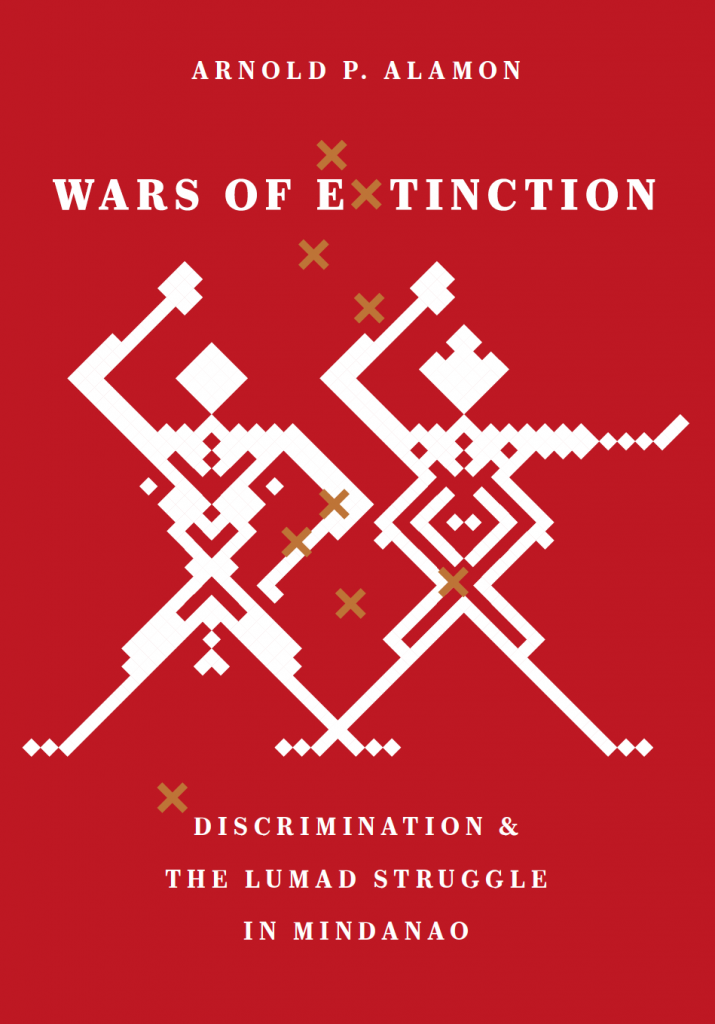

It was as a student member of IPEG that Prof. Alamon first encountered Dr. Paz, whom he fondly called his “first real boss”. His lecture entitled “Postscript to Wars of Extinction: Lumad Identity and Struggle”, built on discourses that arose to contest the term Lumad after the release of his book, “Wars of Extinction: Discrimination and the Lumad Struggle in Mindanao” in 2017.

His interest in the Lumad, however, began nearly two decades ago when, as a member of IPEG, he would go to the field to live among the Ata Manobo in Davao del Norte. Here, in the margins of the Christian settler majority and a Dole plantation, Prof. Alamon said he first encountered the word “Lumad” in a real sense.

While originally coming to research Ata Manobo cosmology and indigenous words and meanings, Prof. Alamon’s interest was instead sparked by the revolutionary songs he heard from two informants. Though the paper he wrote about the topic back in Manila was rejected by Dr. Paz, it became the spur that inspired Prof. Alamon to “chart his own path” and investigate the political and historical aspects of Lumad identity and struggle.

Part of this journey culminated in the release of his 2017 book, which aimed to highlight the decades-old struggle of indigenous communities versus extractive industries allegedly backed by the Philippine military and paramilitary forces. “The term Lumad became synonymous with the plight of an oppressed minority at the hands of the government,” he said, and all this at a time when a supposed non-authoritarian, liberal government was in power.

By highlighting the political and historical aspects of the formation of Lumad collective identity, Prof. Alamon’s book eventually ran into criticisms, which he discussed. One was the claim that he privileged the political Lumad voice over the apolitical voice. While acknowledging this claim, Prof. Alamon said that we should also “know better.” “Not all voices are equal and not all identity claims made on mere utterances are all valid,” he explained. “Yes, they should be listened to and recognized but they should be–like all other claims–measured if found wanting.”

The other was reconciling the confusion of Lumads who turned their back on collective struggle to benefit themselves and their families. He decried the shifting of some Lumads’ allegiances from leftist causes due to state intimidation despite their shared history of dispossession. The way out of this conundrum, he said, was through theory: “what is theory but distilled lessons from the past, a way of saying this has happened before and […] will most likely resolve into trajectories or directions that are predictable?” Through gathering empirical information, he said, it should be possible to arrive at answers that can assist in emancipatory practice without fetishizing the field.

“One may then say,” Prof. Alamon said, “that one of the explicit agendas of the book was precisely to put forward the argument that the Lumad is a class position born out of development aggression during the Marcos years and continues to assert itself as an identity in the context of the changing conditions even post-Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA).”

Ever since the publication of his book, Prof. Alamon’s thinking on the Lumad has continued to evolve. One new development is his proposal that Lumad identity is a product of three distinct encounters: (1) the proto-Lumad versus the colonial power during the American occupation, (2) the Lumad versus the developmental agenda of the nation state that gave birth to Lumad consciousness, and (3) Lumads and their resistance during the post-IPRA era.

The first encounter, he said, was best illustrated by the case of Datu Mangulayon from the Manobo tribe who, in what Prof. Alamon called a fit of “revolutionary rage,” beheaded Lt. Francis Bolton, the then-colonial governor who helped instigate a system of tribal wards and forced labor in abaca plantations for the Lumad during the American occupation in 1906.

After the country was granted independence post-World War II, the Lumad would then come into conflict with the developmental agenda of the Philippine nation state. Through imposed logging, cattle ranching, and mining, the ethnolinguistic tribes began to realize their collective experience of dispossession. Thus, with the help of the Social Action Center of the Catholic Church, the term Lumad would begin to be used to refer to non-Christianized, non-Muslim tribes who experienced dispossession and violence. The Lumad Mindanao People’s Federation would form in 1986, emphasizing the Lumad’s collective right to land and self-determination.

Finally, despite the IPRA being a “pioneer document… for protecting IP rights” the Lumad continue to suffer to this day according to Prof. Alamon from the same forces. This period, he added, is marked by the rise of fake indigenous leaders who abused the free and prior informed consent (FPIC) system and state bodies fronting for exploitative institutions rather than protecting indigenous people’s rights.

Repression, however, he noted, has always given rise to resistance. From Datu Mangulayon’s daring feat to the 2015 Manilakbayan, which was held in part as a response to extrajudicial killings by state forces in the Lumad schools in Lianga, Surigao del Sur.

“The ultimate lesson in looking at these three encounters,” Prof. Alamon said, “is that the dispossession and violence continues until the present. But these have always been met with valiant, creative resistance that doesn’t always win yet persists.”

Ultimately, Prof. Alamon made the claim that the term Lumad as an ascribed identity has transcended its place of origin and is now available to all Filipinos. “We can once again become Lumad and Filipino once we recognize how we have become ruled and divided, betrayed and oppressed by both our colonial rulers and our national elite.”

All these conclusions would not have been reached, however, had Prof. Alamon not worked with Dr. Paz nearly 20 years ago. His original paper on Lumad revolutionary songs may have been rejected, but he thought he saw a hint of “chuckling approval” on the then-Dean’s face. “She probably knew somehow that this presentation would be delivered in her honor decades later,” he remarked.

“Knowing how she was a champion of the social sciences in service of the Filipino people, our gathering here together would surely make her mighty pleased.”

Prof. Alamon’s lecture was followed by a reaction given by UP Department of Anthropology Assistant Professor Reginaldo Cruz, who talked more about the issues related to the use of the term Lumad in representing the cultural and ethnolinguistic diversity in Mindanao as well as the similarities in the struggles that minoritized groups face.

The 3rd Consuelo J. Paz lecture was live-streamed on the UP Department of Linguistics’ social media pages. It also featured a performance by the ethnic music and dance ensemble Kontemporaryong Gamelan Pilipino (Kontra-GaPi). The recording of the event can be viewed at the Department’s Facebook page.

Published by Mai Andre Encarnacion