“It seems like a random phenomenon to look at–as it is not that important in the description of the grammars of different languages–but we believe that if we get a better understanding of this, then we will get a better understanding of agentivity,” Visiting Research Fellow Dr. Sonja Riesberg (CNRS – LaCiTO & Universität zu Köln) said about natural forces in the third installment of the 2024 Linguistics Special Lecture Series (LSLS) last 03 July at Palma Hall Room 1323, UP Diliman.

The lecture, with the title, “Some natural forces are animate agents,” provided cross-linguistic evidence “for the claim that some natural forces sometimes behave like animate agents.” It featured Riesberg and Visiting Research Fellow Dr. Maria Bardají i Farré (Universität zu Köln). The work has also been jointly done with Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Semra Kizilkaya, and Jonathan Reich.

According to them, their research started when they were studying limited-control constructions (i.e., where the agent-like argument lacks full semantic control of the action expressed by the agreeing verb) in western Austronesian languages. This construction is also sometimes referred to as the potentive or accidental function. An example in Tagalog would be the na– prefix, like in the sentence Nadapa ang bata ‘The boy tripped.’ Here, the agent bata is not in full control of the action of tripping.

The visiting research fellows of the Department for the midyear term. From the left: Dr. Jed Sam Pizarro-Guevara (University of Massachusetts Amherst), Dr. Maria Bardají i Farré (Universität zu Köln), Alessa Farinella (University of Massachusetts Amherst), and Dr. Sonja Riesberg (CNRS – LaCiTO & Universität zu Köln).

Animacy in grammar

Typologically, some languages make grammatical distinctions between animate (or living) and inanimate referents. In Patz (2002)’s data on the Kuku Yalanji language, for example, animate referents are morphologically marked with the ergative case, while inanimates are given the instrumental case. This is not an unusual pattern, and the presenters claim that functions like these are often treated as a “sidenote” in grammar.

Interestingly, natural forces in Kuku Yalanji and many other languages often pattern with animates (i.e. they take ergative case marking) rather than with inanimates.

Limited-control constructions and natural forces

The lecture is specifically focused on limited-control constructions in western Austronesian languages like Tagalog, as the pattern has been the subject of their earlier study published in the Oceanic Linguistics journal. These functions, according to them, are not used when the ability of the effector (or agent-like) to control an event is not at issue. With this, animate effectors may occur in both neutral and limited-control predicates, while inanimate effectors cannot occur in limited-control constructions.

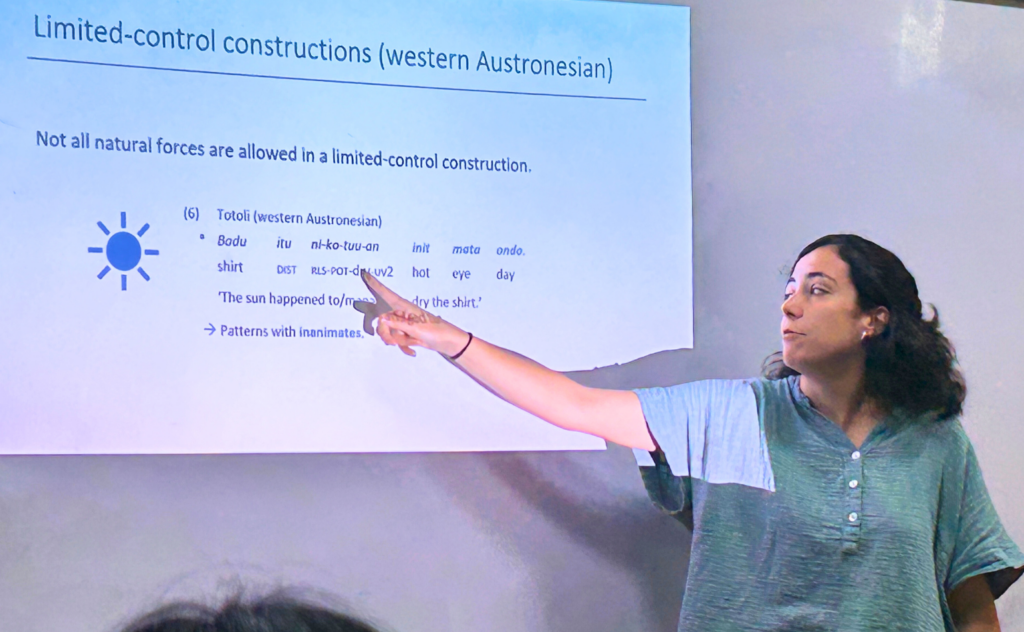

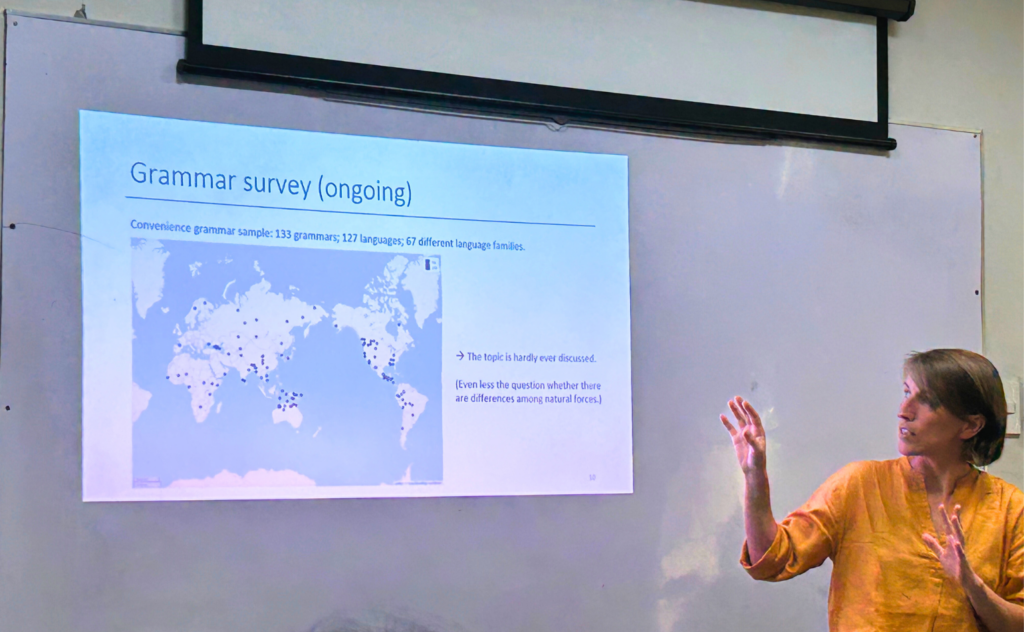

However, going back to Tagalog na-, we can see that natural forces are allowed in limited-control constructions like in Natangay ng hangin ang balahibo ‘The wind (accidentally) swept the fur/feather away.’ Still, in the case of Totoli, ‘sun’ patterns with the restrictions on inanimates. In their ongoing survey of digitally available grammar sketches across the globe, it has been observed that in the current 133 collected grammars of 127 languages, the topic is hardly discussed.

The types of natural forces

Near the conclusion of the presentation, it has been proposed that typologically, there might be three different classes of natural forces, as expressed in their morphosyntactic behavior: those that a) pattern with animates, b) pattern with inanimates, or c) may pattern with both. The data is still however limited to provide a conclusion, so more research has to be done–like that of experimental linguistic findings on English, and those from observed patterns in Philippine languages. They also added the need for its interface with language documentation, as they requested to include this function in the grammars that linguists are working on, since it not only leads to a better understanding of the language, but would also contribute to the improvement of theories and frameworks related to it. “This whole pattern on natural forces is not just some sporadic phenomenon, but a systematic one.”

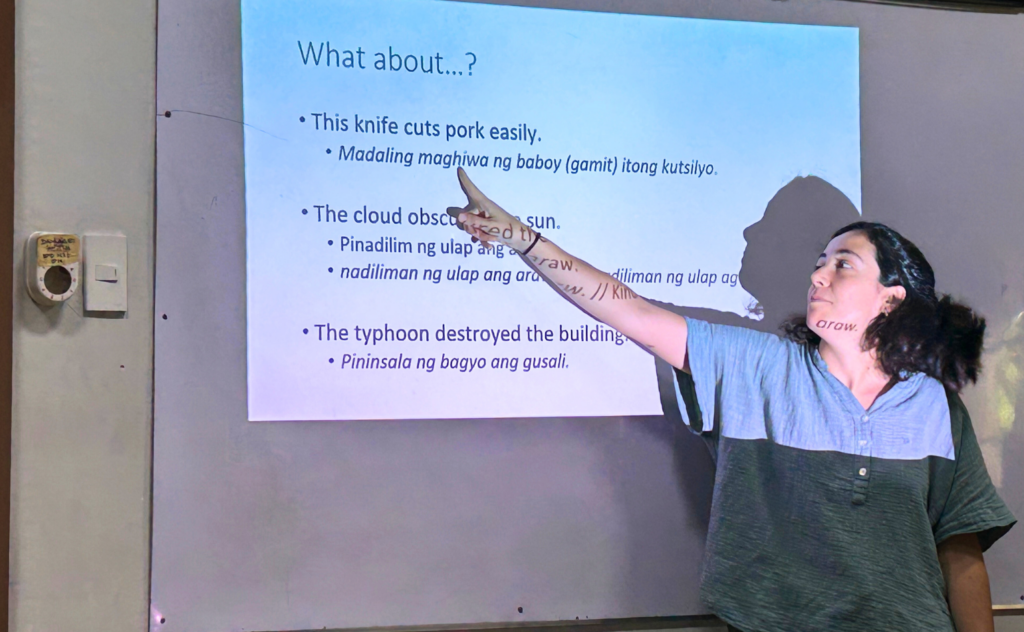

At the end of their presentation, the visiting research fellows tested the acceptability of sentences like Madaling maghiwa ng baboy (gamit) itong kutsilyo ‘This knife cuts pork easily,’ Pinadilim ng ulap ang araw ‘The cloud obscured the sun,’ and Pininsala ng bagyo ang gusali ‘The typhoon destroyed the building.’ Those interested in participating in experimental studies may regularly check the Department’s website and social media pages as different experiments are being conducted this midyear term, with some running until the last week of July.

Also tune in on our digital spaces for updates on future events!

Published by UP Department of Linguistics