Alangan

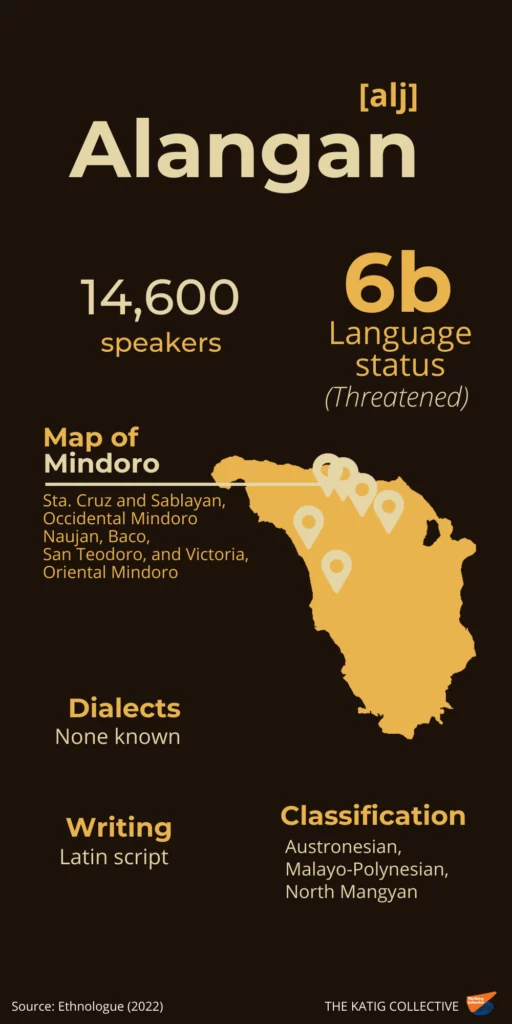

Alangan [alj] is classified as a threatened language (EGIDS 6b*), which means that it is losing speakers despite being utilized in daily conversations across all generations (Eberhard et al., 2022). The schools that provide basic education for the Alangans are projects of non-government organizations, and since the teachers do not belong to the community, Tagalog [tgl] is used as the medium of instruction. A lot of Alangan elders also lament the fact that the youth does not wish to come back to their community after pursuing education elsewhere and would rather live in the lowlands for better economic opportunities.

Ancestral lands as Alangan’s identity

Alangan Mangyans live in the municipalities of Naujan, Baco, San Teodoro, and Victoria in Oriental Mindoro, and in the municipalities of Sta. Cruz and Sablayan in Occidental Mindoro. The concepts of ancestral domain, sustainable development, and eco-spirituality are deeply rooted in their cultural identity. In the past, land was communal and treated as an endowment of the community. The forest also provided them with their primary needs (Adventist Frontier Missions, n.d.). Moreover, the Alangan Mangyans believe that land is owned by their god Ambuwaw. They thus regard their ancestral land not only as a source of sustenance but also as a sacred place—a space for interaction with the creator and gods (Garinguez, 2008).

Present struggles

They strive to keep their ancestral lands but are forced by drilling and mining operations to retreat further into the mountains (Adventist Frontier Missions, n.d.). This foreign endeavor spells the exploitation of natural resources and disregards the cultural values of ethnolinguistic groups. Mining projects also come with other threats like militarization and the subsequent violation of the people’s rights.

More changes and challenges

Although Alangan Mangyans are aware of the negative impacts of acculturation on their cultural heritage, they also recognize the need to adapt to the changing environmental, social, and economic milieu. This is especially evident in the younger generation who fear being discriminated against by low-landers in schools and would prefer to use Tagalog instead of Alangan. The decline in the speaker population can also be attributed to their shift from the communal balaylakoy, a shared living space for up to 20 families, to individual houses. The balaylakoy is important because it serves as the center of Alangan life where activities like chanting, telling stories, and handicraft-making are conducted. It is also where the aplaki (‘elder, healer’) educates the youth on the traditions and values of the community (Department of Social Welfare and Development, 2016).

References

Adventist Frontier Missions. (n.d.). Alangan. https://afmonline.org/serve/detail/alangan/

Department of Social Welfare and Development. (2016, June 7). Reawakening of the Mangyan Alangan culture. https://www.dswd.gov.ph/reawakening-of-the-mangyan-alangan-culture/

Eberhard, D. M., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2022). Alangan. Ethnologue: Languages of the world (25th ed.). https://www.ethnologue.com/language/alj

Gariguez, E. A. (2008). Articulating Mangyan-Alangans’ indigenous ecological spirituality as paradigm for sustainable development and well-being [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Asian Social Institute.

Hammarström, H., Forkel, R., Haspelmath, M., & Bank, S. (Eds.). (2022). Spoken L1 language: Alangan. Glottolog 4.6. https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/alan1249

Open Language Archives Community. (n.d.). OLAC resources in and about the Alangan language. http://www.language-archives.org/language/alj