Ata

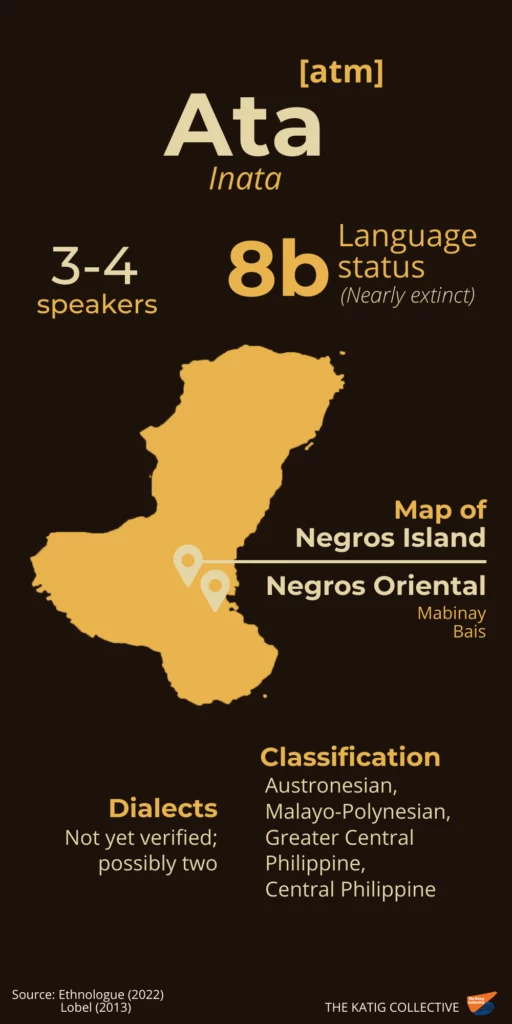

Ata [atm], a Central Philippine language, is spoken by three or four people in the remote upland areas of Mabinay and Bais, Negros Oriental. The remaining speakers belong to the elderly generation (Lobel, 2013), and the language is classified as nearly extinct (EGIDS 8b) in Ethnologue (Eberhard et al., 2022). Ata, also referred to as Inata, was originally spoken by a community native to the northern and south-central mountainous parts of Negros Island. At present, nearly all members speak Cebuano [ceb] or Northern Binukidnon [kyn], with a few more speaking Hiligaynon [hil] (Rahmann & Maceda, 1955; Cadeliña, 1988; Lobel, 2013).

Population estimates

Even before the turn of the century, Ata has already lost ground to neighboring languages with Rahmann and Maceda (1955) explaining that aside from an old woman who did not show up for an interview and an old man who was completely deaf, none of the Ata of northern Negros were reported to speak the language. Earlier studies even considered Ata extinct (Pennoyer, 1986 as cited in Lobel, 2013) but a generous estimate was made for the south-central region with Grimes noting the existence of 25 speakers in Mabinay in 2000 (as cited in Headland, 2003). And although Cadeliña estimated that there were 450 Ata speakers in the whole Negros Island in 1980 (as cited in Headland, 2003), she later remarked that the Ata “have completely lost their traditional language and are now monolingual” (Cadeliña, 1988, p. 63). There is also an apparent inconsistency in the number of remaining speakers due to the remoteness of their locations (Lobel, 2013). Some possible reasons for the historically low number of Ata—both the speakers and the ethnic members—include diseases, intermarriage, and in-migration (Cadeliña, 1988; Rahman & Maceda, 1955; Oracion, 1996).

Works about Ata

No works about the language are available online except for an SIL wordlist on Ata of Mabinay (Bunnie, 1973), and Lobel’s (2013) brief description of the language’s state and estimated speaker population. There is thus a need to conduct more studies on the language and the speaking community.

References

Bunnie, M. (Comp.). (1973). Ata Negrito – Mabinay wordlist. SIL International. https://www.sil.org/resources/archives/77201

Cadeliña, R. V. (1980). Adaptive strategies to deforestation: The case of the Ata of Negros Island, Philippines. Silliman Journal, 27, 93–112.

Cadeliña, R. V. (1988). A comparison of Batak and Ata subsistence styles in two different social and physical environments. In A. T. Rambo, K. Gillogly, & K. L. Hutterer (Eds.), Ethnic diversity and the control of natural resources in Southeast Asia: Michigan papers on South and Southeast Asia 32 (pp. 59-81). Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies. . https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/41858/9780472902309.pdf?sequence=1#page=72

Eberhard, D. M., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2022). Ata. Ethnologue: Languages of the world (25th ed.). https://www.ethnologue.com/language/atm

Hammarström, H., Forkel, R., Haspelmath, M., & Bank, S. (Eds.). (2022). Spoken L1 language: Ata. Glottolog 4.6. https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/ataa1240

Headland, T. N. (2003). Thirty endangered languages in the Philippines. Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session, 47(1), 1-12. DOI: 10.31356/silwp.vol47.01

Lobel, J. W. (2013). Philippine and North Bornean languages: Issues in description, subgrouping, and reconstruction [Doctoral dissertation, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa]. ScholarSpace. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/101972

Oracion, E. G. (1996). The ecology of ethnic relations: The case of the Negritos and the upland Cebuanos in southern Negros, Philippines. Convergence, 2(2), 69-77. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352651269_Ecology_of_ethnic_relations_The_Case_of_the_Negritos_and_Upland_Cebuanos_in_Southern_Negros_Philippines

Rahmann, R., & Maceda, M. N. (1955). Notes on the Negritos of Northern Negros. Anthropos, 50(4/6), 810–836. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40450358